Conservation Easements

An apt tool to protect remaining wetland and grassland in Western Canada.

By Chad Lawley

Conservation easements, which permanently remove the right to convert existing wetland and grassland in exchange for a one-time payment, have become an increasingly popular tool with conservation agencies in Canada and the U.S.

Landowners voluntarily enroll their land in conservation easements. This leads to problems of adverse selection, where landowners and farmers with the lowest costs of compliance are also the landowners and farmers who are most likely to voluntarily enroll their land. This implies that the “additionality” – the level of additional conservation undertaken that would not have taken place in the absence of the payment – in conservation easements is potentially low. This is particularly true in conservation easement programs that constrain future land-use changes but do not require “new” conservation activity.

The impact of conservation easements on farmland values reflects the additionality of the habitat protected by the easement. If the conservation agencies are placing easements on habitat that’s at little risk of conversion, then easements should have very little impact on farmland prices.

Alternatively, if easements are placed on habitat offering the highest levels of additionality – where the benefit of converting existing wetlands and grassland far exceeds the cost – the easements will have a substantial impact on farmland prices. If the conservation easement program is operating as expected, then the average impact of easements on land values be less than the per acre payment for easements. Landowners are not expected to voluntarily enroll land in an easement if the per acre easement compensation payment is not adequate.

Land use change is a persistent feature of western Canadian agricultural landscapes. These changes are driven by a combination of market and government incentives that influence the relative returns to different land uses.

For instance, changes due to U.S. biofuel policy, government subsidized crop insurance, agronomic advances (such as improved crop cultivars, and adoption of larger farm machinery), all influence the net return to converting wetlands or grasslands to more intensive annual cropland.

One approach to quantifying changing incentives is to look at the impact of wetland and grassland acres on the price of farmland. Land parcels with more acreage in wetland and grassland are expected, on average, to sell at a discount relative to parcels with more cropland acreage. Shifts in incentives to convert wetland and grassland are captured by changes in land value discounts over time.

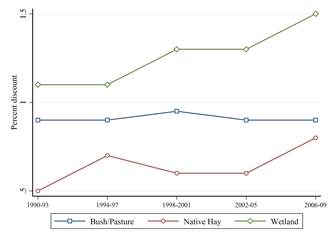

An analysis of farmland price discounts in the Prairie pothole region of Manitoba spanning 20 years (1990-2009) suggests that in the early 1990s, a one per cent increase in the share of a farmland parcel in wetland reduced the sale price by just over one per cent.

Similarly, a one per cent increase in the share of the parcel in bush and pasture reduced the sale price by a little less than one per cent, and a one per cent increase in the share in native hay reduced the sale price by half a percentage point. These discounts are consistent with expectations.

The results also suggest that the discounts on wetland and grassland acreage have increased over time. The effect is most pronounced for wetland acreage; by the late 2000s, a one per cent increase in the share in wetland reduced farmland sale prices by 1.5 per cent, representing a 40 per cent increase in the discount on wetland acreage over the 20-year period.

Whereas wetland drainage and cultivation of grassland was historically encouraged by federal and provincial governments, conservation organizations such as Nature Conservancy Canada, Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC), and the Manitoba Habitat Heritage Corporation (MHHC), now take steps to slow the disappearance of remaining wetlands and grasslands.

Until roughly 20 years ago, conservation agencies typically relied on fee simple land purchases and shorter-term programs to influence land-use choices in Western Canada.

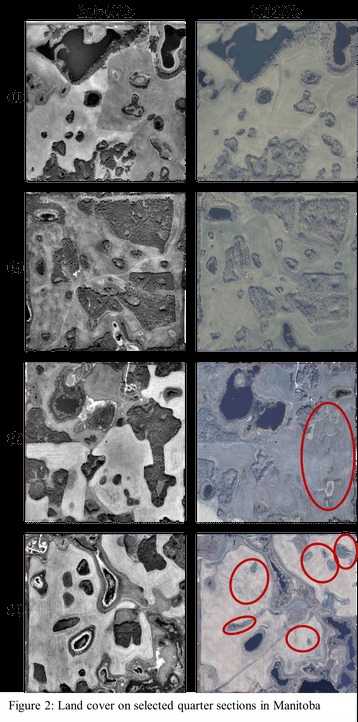

From a conservation agency's perspective, identifying the wetland and grassland most at risk of conversion is challenging. A relatively small share of wetland and grassland is converted each year, but these small changes can amount to substantial changes in the landscape over several years. The figure in this article follows four quarter sections of land in Manitoba over a little more than a decade.

There appears to be no land use change on the first two quarters sections, whereas the several acres of wetland and grassland on the last two quarter sections are converted to crop production at some point between the early 1990s and mid 2000s.

Given limited resources, a primary challenge facing conservation agencies is to try to protect the wetland and grassland at risk of conversion, as in the last two quarter sections, and to avoid paying for the wetland and grassland in the first two quarter sections.

Research examining conservation easements purchased by DUC and MHHC between 2000 and 2013 suggests that farmland prices are reduced by an average of $86 per acre in a conservation easement. This estimated discount suggests that the conservation easements were placed on wetlands and grasslands at risk of conversion.

Over the course of the study period, the per acre payment for a conservation easement was approximately $100 per eased acre. Landowners therefore earned a premium on easement payments of approximately 16 per cent—landowners were able to enrol land in easements when it made financial sense to do so.

Overall, the conservation easement program appears to operate as expected: conservation groups are successfully targeting wetlands and grasslands at risk of conversion and landowners are capturing premiums on easements payments.

Chad Lawley is a professor in the Department of Agribusiness and Agricultural Economics at the University of Manitoba.

Note: This article draws on research summarized in: Lawley, Chad. 2019. “Land Use Change in Agricultural Landscapes: Incentives and Conservation Programs,” Canadian Agri-food Policy Institute (CAPI).