Source: Field Crop News

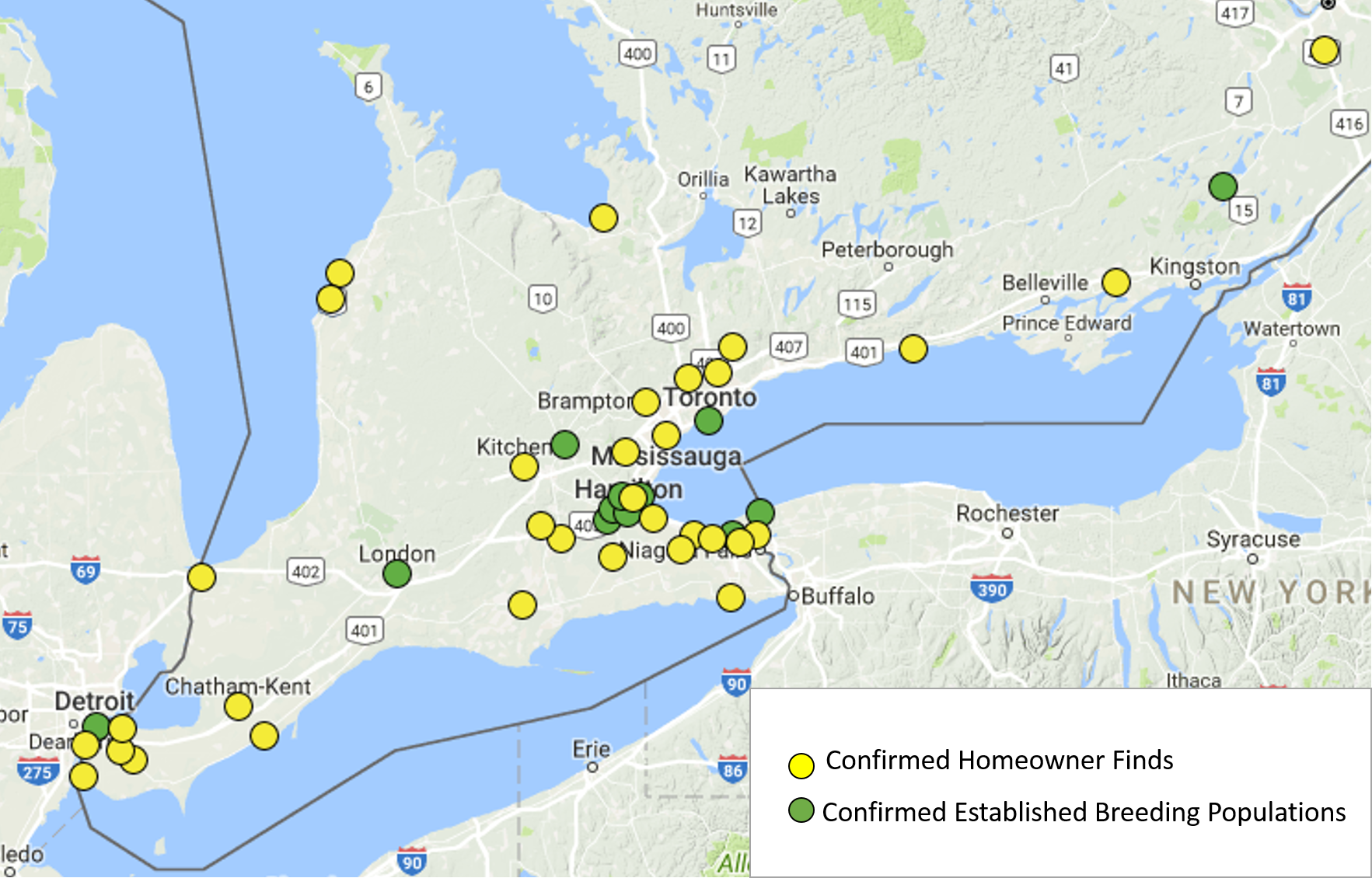

Homeowners play a big role in searching for these pests, as the BMSB may survive in houses over the winter, Baute said in an interview with Farms.com.

“Having a good, in-focus photo of the specimen or saving the specimen to send to us is necessary for us to confirm identification,” she said.

Individuals who believe they have found a BMSB “can collect the insect in a vial or plastic container and put it in the freezer until it can be sent to (OMAFRA),” she added.

During the warmer months, the BMSB may find shelter on various hosts, “including a variety of fruit trees, berries, grapes (and) vegetables, (as well as) field crops including corn, soybeans and edible beans,” Baute said.

The BMSB is of concern as it “is very flexible in moving from one host to another, finding the ideal plant stage (it) requires to live.”

The insect may cause damage that “not only impacts yield and quality, but (also) allows the introduction of secondary pathogens to develop on the wound sites,” said Baute. “Often this injury is only noticed at harvest when it is too late to manage.”

Given the potential threat the BMSB poses to horticulture and cash crops, OMAFRA is closely monitoring the movement of the pest.

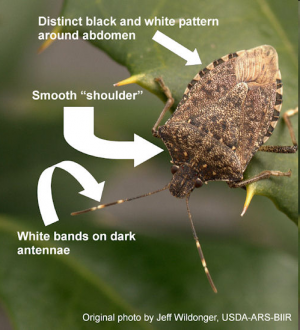

The BMSB can be distinguished by its smooth shoulders, distinct white triangular pattern on the abdomen and the white bands on the antennae, Baute explained in her post.