By Dr. Michelle Arnold

Dewormers (anthelmintics), when given correctly, are not killing intestinal parasites of cattle as they used to. Although new drug “classes” entered the market from the 1950s to the 1980s, it has now been over 40 years since ivermectin was introduced in 1981. Basically ‘we have what we have’ which is 3 major chemical classes or families of dewormers known as the Benzimidazoles (SafeGuard® & Panacur®/ Valbazen®/Synanthic®), the Macrocyclic Lactones or MLs (Ivomec®/ Cydectin®/ Eprinex® & LongRange®/Dectomax®/generic ivermectins) and the Imidazothiazoles/ Tetrahydropyrimidines (Rumatel®/ Strongid®/ Prohibit® or Levasol®). These dewormers are gradually losing effectiveness against livestock parasites with no new products on the horizon to replace them.

“Anthelmintic resistance” is the phrase used for the ability of a parasite to survive treatment with a lethal dose of chemical dewormer because of a change in the genetic makeup (mutation) in the parasite. Only the parasites that survive after deworming will go on to reproduce and may pass a copy of their newly formed “resistance gene” to their offspring. But this is only half of the story. For fully resistant parasites to develop, both parents must pass a copy of this “bad” gene to the offspring. These resistant genes build up slowly but steadily in the parasite population, especially from repeated use of dewormers over many years, and they do not revert to susceptibility. Resistant worms are not more aggressive or deadly; they simply survive in higher numbers after deworming, resulting in production loss and disease in the most susceptible animals.

Consequences of high parasite burdens are mostly seen in younger animals, especially weaned calves and replacement heifers, since adult cattle develop an immunity to the effects of parasites. Although most infections in cattle are a combination of several different worm species, generally all gastrointestinal parasites cause anorexia and reduce the animal’s ability to efficiently convert forage to milk and muscle. The number one sign of a parasite problem is lower than expected production, including less than genetic potential rate of gain, feed conversion, growth, and reproduction. This is potentially costing producers due to reduced weaning weights, delayed puberty, decreased fertility and pregnancy rates, reduced feed efficiency and immune suppression in young cattle, especially those ages 2 years and younger. As exposure to parasites increases with age, the bovine immune system reduces worm infections and suppresses worm egg production. This immunity to parasites is a moderately heritable trait. Unfortunately, the dependence on chemical dewormers has allowed selection of bulls and replacement females with high production numbers but has ignored any potential genetic contribution to fighting parasites. Additionally, chemical deworming has allowed continued husbandry and pasture management factors that keep worm burdens high. As an example, overstocking a pasture results in more feces, more worm eggs and larvae after egg hatching, shorter grass and more parasites in animals forced to graze near manure piles. Young, growing animals are at highest risk due to lack of previous exposure to parasites and a naïve immune system.

How is it possible to know if dewormer resistance is a problem in a herd? The best way to test is a Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) based on the knowledge that dead worms don’t lay eggs. This test basically involves taking fecal samples from 20 random animals within a production group (cows, calves, or replacement heifers) at the time of deworming and sending them to a laboratory for a fecal egg count (FEC). Fecal samples are collected again from the same production group 14 days later and those samples are sent to the same laboratory for a second FEC. The second samples do not have to be collected from the same individual animals but do need to be from the same group collected previously. If the dewormer worked effectively, there should be at least a 90% reduction in the average or mean number of eggs from the first sample to the second sample. “Resistance” is present when the correct delivery of the correct dose of the dewormer to a healthy animal fails to produce at least a 90% reduction in the number of parasite eggs. It is important to understand that a decrease in “anthelmintic effectiveness” or “treatment failure” may be for reasons other than genetic or heritable resistance in the parasite population. Many factors can cause smaller than expected reductions in fecal egg count numbers including underdosing dewormers from errors in weight estimation, dosing equipment not calibrated correctly and/or not working properly, applying pour-ons to the hair of an animal rather than skin, use of expired products, and errors in sample collection and shipment, just to name a few.

How can we slow the development of resistance to dewormers? First and foremost, we must understand the parasite prevalence (the proportion of cattle with a large parasite load in each time period) in KY cattle in order to properly direct research and extension interventions to lessen the effect of parasites on health and production. Secondly, we have to examine the current level of resistance to dewormers through FECRTs performed throughout the Commonwealth. Finally, it is important to identify the predominant types of gastrointestinal parasites in our cattle to correctly interpret the FEC. Most of the major parasites in cattle are classified as “strongyles” and their eggs are basically indistinguishable. Weaned calves up to 12-18 months of age are mostly affected by two strongyle species, Cooperia and Haemonchus, both of which produce huge numbers of eggs. Around 2 years of age, cattle develop resistance to Cooperia and Haemonchus but another strongyle, Ostertagia, a more pathogenic parasite predominates yet it does not produce many eggs. A PCR is now available to identify the parasite genus and species as there are concerns that climate change, intensive livestock management and dewormer resistance issues have fundamentally changed our picture of “expected” parasite burdens in production classes of cattle. To accomplish these three tasks, UK Extension faculty and agents, in conjunction with KBN and Merck Animal Health, have launched a parasite study that is set to begin in the Spring of 2023 in beef cow/calf and stocker operations in KY and we need your herds.

To participate, collaborating herds must be planning to administer a dewormer in BOTH the spring and fall of the year. Producers may use any dewormer they normally use or one recommended by their veterinarian. It is important to understand that dewormer will NOT be provided to participating herds! Fecal samples will be collected twice in the spring and twice in the fall from the same group of animals. Producers will be asked to complete a short questionnaire requesting basic information on the herd. Once all the data is compiled, the information will be shared with the producer and his/her veterinarian, if desired. If you wish to be considered for enrollment in this important study, please contact your local County Extension agent and convey your interest in joining.

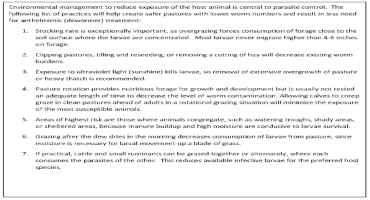

Reducing unnecessary treatment with dewormers, making sure the dewormers used are effective, and making sure deworming is performed correctly all contribute to fewer resistant genes in parasites. In addition, environmental management (see box below) will help create safer pastures and lessen the need for chemical dewormers.

Source : osu.edu