By Bruce Potter

Once again this spring, cooperators across Minnesota have been checking pheromone traps for black cutworm (BCW) moths migrating into the state from overwintering areas in the south.

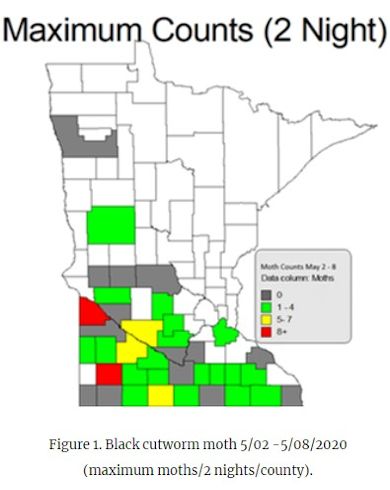

Last week, their traps have picked up more immigrating black cutworm moths; particularly in the western part of the state where two traps had significant captures (Figure 1).

The southerly system on May 4-6 provided the largest number of moths. A Lac Qui Parle County trap captured 9 moths May 5th-6th and a Murray County trap captured 12 moths over the same period. Traps in other counties also captured moths throughout the week.

Fortunately, when and where, these larger flights arrived in Minnesota, most corn and sugarbeet, and many soybean fields, had been already been worked and planted, thereby reducing their attractiveness to moths laying eggs.

Risk of economic damage

While the timing of 2020 BCW moth arrival into Minnesota is similar to 2019, the frequency, distribution and magnitude of the flights have been much less. When these data on this year’s fewer and smaller flights are combined with the early planting in the southern portion of Minnesota, the risk of economic damage appears low compared to many years. This risk, however, is not zero.

Black cutworm moths arriving in Minnesota seek out areas with crop debris, sheltered areas, and low-lying spots in the field to lay eggs. Any early season weed growth is very attractive to the moths. Areas with dense populations of winter annual (e.g. shepherds’ purse) and early spring emerging broadleaf weeds (e.g. lambsquarters) are often infested. Similarly, overwintering cover crops might attract egg-laying moths and black cutworm damage associated with winter rye has been observed in Minnesota corn.

Unworked fields, or fields with reduced tillage and more crop debris is on the surface, attract more egg laying moths. Fall tillage that buries crop residue and spring tillage that eliminates early spring weed growth before the flight arrives reduces the risk and severity of black cutworm attack. Historically, soybean residue is more attractive than corn, but this may be in part due to the amount of fall tillage or to species and numbers of broadleaf weeds in the seedbank between the two crops.

Focus your scouting efforts

How do you focus your scouting efforts for black cutworm? Fields that are at highest risk are fields that had not been worked when moths arrive, fields with winter annuals or early spring emerging weeds and in the case of corn, field planted to hybrids without a Cry1F (HX1) or Vip 3a (Viptera) above-ground Bt traits.

In the case of corn, scouting for black cutworms should start before 300 degree-days (base 50 F) accumulate after a significant moth capture (eight or more moths/2 nights) occurs. This is about three weeks in a typical Minnesota spring but will, of course, happen sooner if warm and later if cool. Eggs hatch and leaf feeding begin at 90 degree-days so early scouting of small broadleaf seedlings, such as sugarbeets, is important. For a couple of the smaller, early black cutworm immigration events and this week’s significant captures, predicted dates for the start of leaf-feeding and for the beginning and end of cutting are shown in Table 1.

Although we did not have any significant flights until May 5-6, there may already be some leaf-feeding from larvae resulting from earlier migrants. These larvae might be large enough to cut corn as early as May 24th. Since both BCW and frost injury prefer low–lying areas, the recent 4-5 night freeze event could make scouting more difficult in some parts of Minnesota.

Table 1. Estimated black cutworm development for significant moth captures as of May 22. Current and forecast degree-days (DD) are generated from the U2U Corn Growing Degree-Day application at the Midwest Regional Climate Center https://mrcc.illinois.edu/U2U/gdd/ using current year and NWS forecast temperatures.

| County | 2-night capture | Biofix date | Post-flight DD as of 12-May | Est. current max BCW stage | Est. start corn leaf feeding1 | Est. start corn cutting2 | Proj. end of cutting3 |

|---|

| Rock | 4* | 21-Apr | 167 | 1st - 3rd | 30-Apr | 24-May | 15-Jun |

| Brown | 5* | 28-Apr | 122 | 1st - 3rd | 8-May | 29-May | 18-Jun |

| Lac Qui Parle | 9 | 6-May | 17 | Egg | 19-May | 4-Jun | 23-Jun |

| Murray | 12 | 6-Jun | 18 | Egg | 19-May | 5-Jun | 24-Jun |

| *Less than a significant two-night capture. |

1Based on a 90 degree-days (base 50F) after significant flight (leaf feeding begins).

2Based on a 312-degree-days (base 50F) from significant flight. 4th-6th instar larvae are large enough to cut corn. Small plants (e.g. sugarbeets) can be cut earlier.

3Based on >641 degree-days (base 50F) after a significant flight pupation.

Source : umn.edu