By Hannah Ritchie

Climate change could have large impacts on food production across the world.

I explored this in my previous two articles, looking at the impact of climate change on food production so far, and what we might expect in the future.

In short, it might boost crop yields at high latitudes but negatively impact yields in the tropics and subtropics. Wheat and rice — which benefit from more carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere — could see yields increase, while maize, sorghum, and millet could see a decline with warmer temperatures. If you want to know more, you can read the previous two articles to get some grounding in the scale and distribution of climate impacts.

This article is the third and final one in this series. It examines whether the world can adapt its food systems to climate change. What are those changes, and can the negative impacts on yields be offset?

These answers are crucial to ensure that countries can further improve food security in a warmer world.

What, where, when, and how: the four ways to adapt crop production

Farmers can adjust their practices in four key ways. They can change:

Farmers can change what they plant. This could be an entirely different type of crop: maize instead of wheat, for example.1 Or a different variety of a specific crop. There isn’t just one variety of maize or rice; scientists breed various "cultivars" with different characteristics and grow best in different conditions. Some are more drought-tolerant than others, for example. Or they take shorter or longer periods to mature and be ready to harvest.

This means farmers can pick crop varieties best suited to different climate conditions.

Farmers can change where crops are planted. If temperatures rise or fall, crop production can shift north or southwards towards more optimal temperatures. In mountainous areas, it can move up and down the slopes. Agriculture can also shift to drier or wetter regions of a country, depending on the local conditions.

Farmers can change when they plant and harvest. Farmers can plant earlier or later in the year, depending on when spring arrives. The same applies to winter crops: they might choose to plant earlier or later in autumn.

Farmers can change how crops are managed. Crops need the right amount of water, nutrients, and protection from pests and disease. Making sure that they have enough through the use of irrigation, fertilizers, and pesticides can help offset some impacts of climate change.

In the following sections, I’ll look at whether these changes can make food systems more resilient to rising temperatures in the future. However, it’s important to note that farmers have already implemented many of these strategies. For example, an extensive study by Lindsey Sloat and colleagues showed that the movement of farming and more irrigation has already offset most of the negative impacts that we’d expect from the 1.3°C of warming that the world has already seen.2

Adaptation can offset many, if not all, of the negative impacts of climate change on crop yields

Before I jump into the specific changes and investments that will allow us to adapt, it’s worth looking at the opportunity we have to make our food system more resilient at a global level.

Here, I’ll focus on a recent study by Sara Minoli, Jonas Jägermeyr, and colleagues.3

The study looks at the impact of climate change on yields of key staple crops — maize, rice, sorghum, soybean, and rice — towards the end of the century under a pretty high (i.e., bad) climate scenario called “RCP6.0”. In this scenario, the world would warm by around 3°C by 2100.4

They look at global yields for each crop (I’ll come on to some regional impacts later) under scenarios with and without adaptation. Adaptation in their study involves farmers changing the when and what — the timing of planting and harvesting — and picking more climate-suited breeds of crops.

They find that adaptation could offset climate impacts, at least at a global level. Crops such as maize would see yield losses without adaptation but could see an increase in yields with a change in practices and investments in the right places.

Let’s look at what these adaptation measures would mean in practice.

Planting and harvesting crops at different times and using more suitable crop types can improve yields

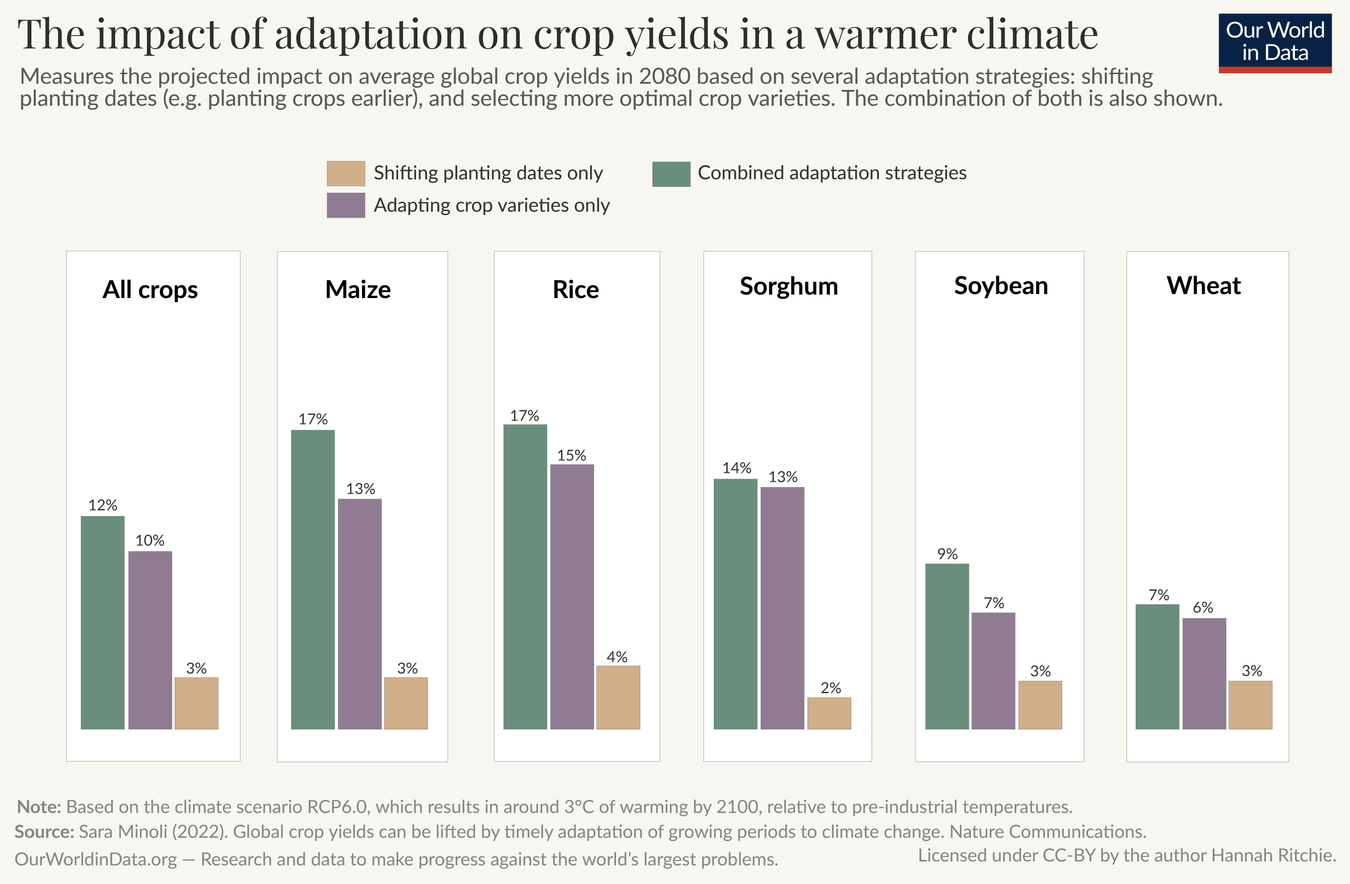

Sara Minoli and colleagues modeled two adaptation methods. The first is changing the dates that farmers planted their crops — in the chart, this is shown in brown.

There are two key stages in the year when farmers plant their crops: either at the start of warm weather for spring crops or the beginning of colder weather for winter crops, such as winter wheat. Climate change will affect the optimal time to plant. Warmer temperatures mean that in many countries, spring crops can be planted earlier.5 For the scenario of 3°C warming, The researchers estimate that toward the end of the century, spring crops in many places should be planted 10 to 30 days earlier than they are today. On the other hand, winter wheat should be planted 10 to 30 days later so the crop doesn’t develop too early or too quickly when it’s vulnerable to damaging conditions like frost.

In the chart below, you can see the estimated impact of changing the sowing date and adopting different crop varieties on crop yields at the end of the century under the RCP6.0 scenario that we looked at before.

At high latitudes — especially across Northern Europe and Canada — farmers who grow spring wheat might benefit from switching to winter wheat.

The second adaptation measure is choosing better-suited crop strains — in the chart this is shown in purple. Through plant breeding, scientists have adapted crop varieties to suit the local climatic conditions. Some varieties will need longer or shorter periods to reach maturity, will be more adapted to warmer, drier, or wetter conditions, have different optimal day lengths, and need different exposures to cold conditions to flower properly. Farmers can, therefore, select better-suited crop varieties over time as the climate changes. They already do this.6

Both measures help farmers to adapt, although changing crop varieties is expected to have a bigger impact on improving yields for all crops. The adaptation benefits for maize, rice, and sorghum are much larger than for wheat and soybean. This is good news because maize, millet, and sorghum could suffer the most from higher temperatures and don’t benefit much from higher levels of CO2. Wheat yields, on the other hand, are projected to increase under climate change regardless of adaptation.

Other studies that focus specifically on the increased risk of waterlogging find that adaptation using more tolerant crop strains, and changes in planting dates can offset many of the declines expected with warming.7

Click here to see more...