By Walt Fick

It has been a late spring in 2022 across most of Kansas. Lack of fall and winter moisture has delayed plant growth this spring. Cool-season pastures of tall fescue and smooth brome are normally producing adequate forage for grazing by April. Turn-out on our native grasslands dominated by warm-season grasses varies across the state from mid-April to mid-May (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Cattle grazing native grass pasture. Photo by Walt Fick, K-State Research and Extension.

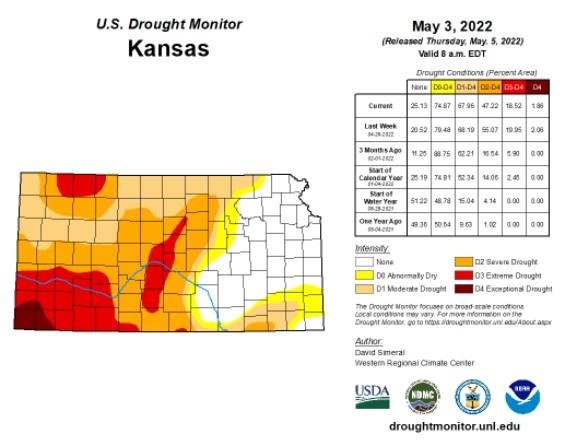

Lack of sub-soil moisture, persistence of drought, and cool temperatures have slowed green-up in many areas of the state. In the last report from the U.S. Drought Monitor nearly 75% of Kansas was experiencing abnormally dry to exceptional drought conditions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. U.S. Drought Monitor for Kansas, May 3, 2022.

The question becomes, when should I turn-out livestock on my pastures? Historically, this decision has been referred to as range readiness, especially on seasonally grazed pastures. Range readiness occurs when plants have had the opportunity to make good growth and grazing may begin without damage to the vegetation or soil.

As pastures start to green-up the temptation is to start grazing as soon as possible. Initially, plants use stored food reserves to start growth. These reserves are stored in the roots, rhizomes, crown, and stem bases, depending on the plant species. Once the plant has enough leaf area, photosynthesis takes over and supplies the energy required for plant growth. Repeated defoliation before sufficient leaf area exists to supply the plant’s energy needs can result in reduced plant vigor and even plant death.

Grasses vary in their resistance to grazing pressure. The amount of leaf area needed before grazing starts varies, but some have suggested that grasses should have a minimum of three leaves. Warm-season grasses that are 2 to 4 inches tall and rapidly growing are ready to graze. Even at this height, dry or cool and cloudy days can reduce plant growth rates allowing the livestock to get ahead of available forage. Remember, a 1200-pound cow will consume over 31 pounds of dry matter per day.

If pastures are not ready to graze, one option is to use deferred grazing. That is, continue to feed or graze alternative forages, such as cool-season grasses, and delay moving animals to native range. Don’t delay too long though, as forage quality declines with plant maturity and livestock gains may suffer. Increased stocking rates may be used with deferred grazing assuming normal plant growth and fewer days of grazing. Another option would be to supplement an energy source for cattle grazing in the early season.

What should a manager do if drought persists and forage production is reduced? Be prepared. The National Weather Service is predicting above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation for the next 30 to 90 days in Kansas. Hopefully, managers have a drought plan in place with specific target dates used for making decisions. Once drought is eminent, implement the plan and stick to it.

If forage production is going to be less in 2022, what can I do about stocking rates? Forage production varies across the state depending on precipitation and ecological site. A common ecological site in Kansas is loamy hills. In a normal year production can vary from 1500 lbs/acre in the west to 4250 lbs/acre in the east. Here are some stocking rates across Kansas with normal and below normal production (lbs/acre) for cow-calf pairs for a 150-day grazing season:

Forage production | West lbs/a | Acres/pair | Central lbs/a | Acres/pair | East lbs/a | Acres/pair |

Normal | 1500 | 16 | 3000 | 7.6 | 4250 | 5.5 |

Below normal | 750 | 32 | 2150 | 10.7 | 3000 | 7.6 |

Normally, we would like to leave 50% of current years’ production. What would utilization be if we have below normal production and want to graze for 150 days?

| West | Central | East |

Utilization (%) | 98 | 72 | 71 |

What are the consequences if we remove more than 50% of current years’ production? At 50% removal of leaf volume, root growth stoppage is minimal, or just starting to occur for a short period of time. As utilization increases, root growth stoppage increases exponentially. At 70% removal of leaf volume, root growth stoppage is 78% and at greater than 80% removal, root growth stoppage is 100%.

Root growth depends on the amount of leaf area remaining after defoliation and the presence of buds to initiate growth. High defoliation rates will not only reduce root growth, but also prune back the root system. Fewer shallower roots will reduce plant vigor, decrease water and nutrient uptake, and make the plants less tolerant of drought.

One way to reduce utilization would be to decrease the length of time animals are grazing. How long can we graze with lower forage production and not decrease stocking rates?

| West | Central | East |

Forage production (lbs/acre) | 750 | 2150 | 3000 |

Acres/pair | 16 | 7.6 | 5.5 |

Days of grazing | 77 | 105 | 106 |

All the examples discussed are based on a cow-calf pair weighing 1500 lbs and consuming 2.6% of their body weight. Adjustments would need to be made for different size or class of animals.

Source : ksu.edu