By Jonathan Coppess

Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics

University of Illinois

As if reminders were needed, the early days of the 118th Congress continue to provide them. The U.S. government reached the statutory debt limit on Thursday, January 19, 2023, requiring the Treasury Department to take so-called extraordinary measures to avoid a default; Treasury’s extraordinary measures are likely to keep the problem at bay until June (Tankersley and Rappaport, January 19, 2023; Tankersley, January 22, 2023). Recently, it was reported that Representative Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) reached a private deal with one of the factions opposing his bid for Speaker to have the House to pass a payment prioritization plan instead of raising the debt ceiling. (Stein, Caldwell, and Meyer, January 13, 2023). The current demand from House Republicans is for President Biden to negotiate an agreement to reduce federal spending (Morgan, January 25, 2023; Sprunt and Jones, January 24, 2023). Speaker McCarthy’s deal-making and the contretemps over the debt ceiling connect back to the concerns of the Framers, begging questions about the design of Congress and the ability to protect the public interest from factions. It serves to introduce an initial critique of the theories in the design and the design, itself, for this fifth installment in the series considering the U.S. Congress.

Background

To review, factions were the mortal disease of all government (farmdoc daily, November 11, 2022). The Framers designed what they called a republican remedy to the mortal disease: government by representation, which avoided many of the problems of an open, Athenian-style democracy; representation allowed for governing an extended republic consisting of a large, diverse population, geographic area and variety of interests or factions. Instead of the cacophony and chaos of an open democracy, a republican form of democracy could be better managed and, in turn, better manage and govern an enlarged society. The extent and diversity of that society—or the various interest groups and factions within it—would have to compete, bargain, negotiate, and compromise with and among each other (farmdoc daily, January 5, 2023). The structural design was extraordinarily critical because it provided the arena for the factional competition at the heart of Madison’s theory. The structure of Congress, more than any other branch, and the procedure and process for legislating, would determine the fairness and effectiveness of that competition. For Congress, the Framers’ created a double majority requirement for legislative enactments, through a procedure requiring passage of identical legislation by both the House and Senate before being presented to the President (farmdoc daily, January 12, 2023). Through this, Madison theorized that the government could arrive at decisions most nearly aligned with or approximating the public’s interest.

Discussion

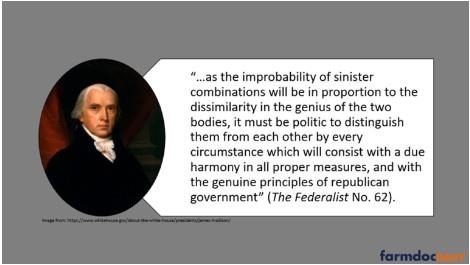

Critiquing the design for Congress and the theories of the Framers is a rather daunting task, to say the least. This attempt will begin with the paradox and conflict at the core: a system of self-government in which the legislative power was intended to achieve outcomes in the public interest, but not by simple majorities of the representatives elected by the public; a representative democracy in which majorities were considered the factional interest of primary concern. The design was not just bicameralism, but a double majority requirement for enactment: a majority of the public, and a majority of the States. According to Madison, the intent was two very different representative bodies with little representation in common, as highlighted by his quote in Figure 1. The “constituency differences between the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate can convert simple majority rule in each house into what is effectively super-majoritarian decision making” (Grofman, Bernard and Brunell 2012, at 158).

Figure 1. Madison on the Double Majority, The Federalist No. 62

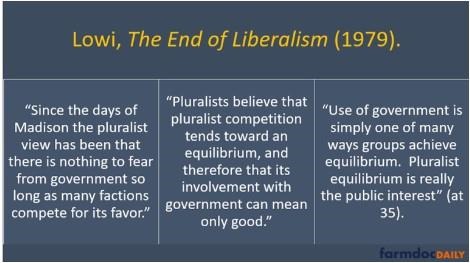

Arguably the most critical component of Madison’s theory was that this double majority system would channel factional political power through political competition. Channeled political competition provided the method for factions to check each other internally, rather than seeking external controls or mechanisms, which were likely to be ineffective at best. Political scientists label this pluralism, theorizing that a pluralist competition among factions provides the method by which the public interest could be achieved. Theodore Lowi, for example, discussed pluralism with some skepticism, as highlighted by his quote in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Excerpt from Lowi’s Discussion of Pluralism

The most obvious concern with designing a system that is based on a theory of competition among factions is whether the competition is fair and effective. The fairness and effectiveness of the competition is where theory meets reality in the operation of government over time. On this score there is reason for concern. While “[n]othing weighed more heavily on [the Framers’] minds” than the “dangers of faction,” Madison’s arguments make clear the extent to which he was “more inclined to stress the dangers that could arise from a willful or tempestuous majority than from a minority; for he assumed that in a republic a majority could more easily have its own way” (Dahl 1967, at 11-12). Bicameralism does not operate “in a neutral way” because “some interests are advantaged at the expense of other interests” depending on how it is designed; for example, Madison “expected that property owners would constitute a blocking coalition in the Senate” and “antebellum slaveholders were advantaged by control of the Senate” (Miller, Hammond, and Kile 1996, at 99). The political competition is stacked against majority interests—and by extension possibly the public interest.

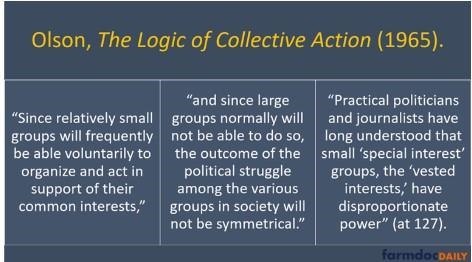

Neither Madison’s theory nor his design distinguishes between a majority operating in the public interest and one that is a problematic factional interest. His arguments discount—if not dismiss outright—the potential that a majority may constitute the public interest, or at least present the most accurate representation of and best version of the public interest. The result was a design that favors minority factions and relies on pluralism to approximate the public interest, creating asymmetries in the competition. It risks empowering minority factional interests by providing them further advantages. This concern is magnified because, according to Mancur Olson, smaller factions will organize and form much easier than larger interests resulting in further advantages in the political competition (see, Figure 3; Olson 1965). This same logic is more applicable to the public interest, which would struggle the most to organize and act in a coordinated, effective fashion.

Figure 3. Mancur Olson on Factional Interests

In addition, as Robert Dahl has pointed out, if “a minority has enough representation to prevent a majority from acting unjustly toward it, it will also have enough representation to prevent a majority from acting justly” (Dahl 1967, at 115). Both Madison and Hamilton acknowledged their willingness to sacrifice some legislation that could be considered in the public’s interest or necessary to a significant—even a majority—of the general public. They considered this outcome acceptable if it prevented enactment of legislation that could be considered bad or problematic because it is not in the public interest or could threaten the rights of individuals or other factional interests. Risking the failure of legislation in the public interest to provide better certainty that bad legislation would be prevented from enactment is a tradeoff that could be “problematic because it is an over-inclusive solution to the problem of unwise or dangerous legislation” (Eskridge, Frickey and Garrett 2006, at 80). It does more than that; this design provides immense protections for the status quo, rendering change, revision or reform extraordinarily difficult. These are challenges that extend to innovations in policy and new ideas or concepts. To the extent that the status quo favors any factional interests, moreover, that faction would be empowered to prevent a majority from acting to reform or revise the status quo from which it benefitted disproportionately, as well as a status quo that was to the detriment of the greater public interest. Here again, the design raises concerns that the competition for legislative outcomes favors some interests over others.

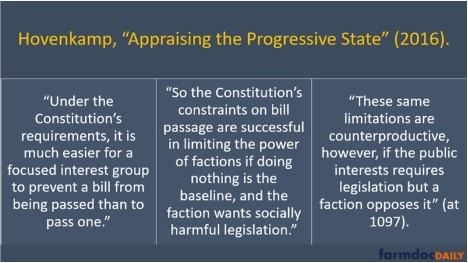

Herbert Hovenkamp has pointed out that the Framers’ design has failed to eliminate capture by factions. He traced the problem to Madison’s assumption “that the effect of factions would show up in efforts to pass legislation, not in efforts to prevent it from being passed” (Hovenkamp 2016, at 1097). Former Senator George Norris (R-NE) criticized the design “because ‘special interests, corporations and monopolies’ find it easier to ‘prevent legislation’ with two chambers than they would with only one” (quoted in Rogers 2003, at 510). This feature of the design is most problematic when the public interest demands legislation that is opposed by a factional interest. The power to block such legislation can provide outsized negotiating leverage to a factional interest to achieve ends that it would not be able to achieve in the pluralist competition—take hostage the public interest to get what a faction wants when the faction could not achieve the double majority on its own. Figure 4 quotes Hovenkamp and the debt ceiling issue currently roiling Congress provides a case-in-point.

Figure 4. Hovenkamp Critique of the Design of Congress

Here the critique stumbles. For example, the “over-inclusive solution to the problem of unwise or dangerous legislation” does not include “a separate track with fewer procedural hurdles for thoughtful, public-regarding legislation” (Eskridge, Frickey and Garrett 2006, at 80). Such a design, however, might be more problematic than the problem it seeks to solve. It is difficult to imagine an effective or acceptable method for determining in advance which policies or bills are good and which ones are bad, in the public’s interest or contrary to it; the internal political competition was to determine such matters. Moreover, governing is not simply a contest to enact legislation, nor is success defined by having enacted more laws than other interests; it is not simply a matter of counting wins and losses. Political competition “is fundamentally about the exercise of public authority and the struggle to gain control over it” (Moe 1990, at 221-23). Achievements in the political competition result in outcomes for the governed, or some portion of it. Those outcomes could impact winners and losers similarly or disparately, such as redistributing public benefits from one faction to another. These realities do not lend themselves to separate tracks, nor to predetermination. A workable alternative remains elusive.

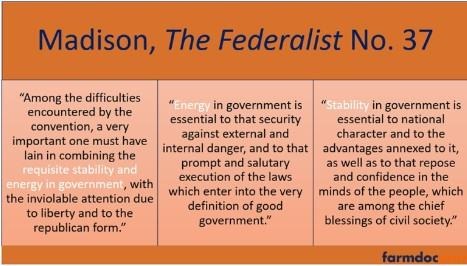

Part of the challenge is the need for stability in government and the potential instability that can result from simple majority rule. Where it is easy for a majority to enact legislation, it is also easy for another majority to change or revoke it and “the problem is that there is usually some alternative that a majority prefers to any status quo” (Miller, Hammond, and Kile 1996, at 84). Except that stability does not result only from preventing change or making it difficult and the “overall volatility of the statutory regime is what is important” (Rogers 2003, at 512). For Madison, the “great desideratum” was to “secure the public good and private rights against the danger” of factional interests “and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government” (Madison, The Federalist No. 10). He explained the intent in terms of combining both energy and stability in the government, as highlighted in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Madison on Combining Energy & Stability in Government, The Federalist No. 37

Bicameralism and the double majority cause legislating to be exceedingly difficult. One result could be a design that is conservative “in the sense that it minimizes change in statutory regimes” and “deter[s] successful legislative activity” (Rogers 2003, at 509-10). Adding another layer of paradox, however, the design could also provide energy and spur innovation. With two different representative bodies “working in large measure independently of one another, it is possible that some of the legislation originating in one of the two chambers would not have been conceived of, let alone enacted, by the other chamber legislating alone” (Id., at 514). The Senate and the House each have veto power over the other’s legislation, but they also each have the power to originate legislation. The concerns highlighted in critiquing the design do not have to be immutable characteristics, which Madison recognized. He wrote, “[w]hat change of circumstances, time, and a fuller population of our country may produce, requires a prophetic spirit to declare, which makes no part of my pretensions” (Madison, The Federalist No. 55).

Concluding Thoughts

Considering Congress in modern light, after substantial history and lived experience, we possess much that the Framers could not know at the time (see e.g., Dahl 2003). Any honest evaluation or review must acknowledge that, but also acknowledge many of the successes of the design over the course of more than 240 years. Any critique threads a difficult needle; the Framers were brilliant and far looking, but also very conflicted and fallible products of their time. Many, like Madison, owned property in enslaved humans while designing aspects of the Constitution to protect property rights. They were also designing not just a new government for a new Nation, but a new kind of government with very little precedent in the history of human society. Intuitively, they were setting up a basic structure and leaving much about it to themselves and future generations to sort out; little about the Constitution was set in stone and fixed for all time, but much of it was to evolve with the people and society. To critique is not necessarily to attack, nor to condemn.

To the extent that the theory for the design was a political, pluralistic competition, the structure stacks the competition against majorities and legislative achievement. By making legislation too difficult to enact, the design risks being too protective of the status quo and renders change or reform too challenging to achieve. Contrary to Madison’s emphasis on factional majorities, the smaller factional interests are more likely to form; combined, these matters all work to empower smaller, factional interests. Arguably, the most important point of the critique and its most significant contribution is to recognize the impacts of the design on this theory of political or pluralistic competition. And while much about the framework or structure cannot be simply changed, this recognition helps focus attention on matters that worsen the original shortcomings and exacerbate the asymmetries, and that can be revised, reformed or improved. One example may be the fact that the size of the House has basically been unchanged for 100 years due to the Permanent Reapportionment Act of 1929 (farmdoc daily, October 27, 2022). Further examples are to be found in other federal statutes, as well as in the rules, procedures and practices. Future considerations of Congress will cover those topics and build upon this initial critique.

Source : illinois.edu