By Greg Halich

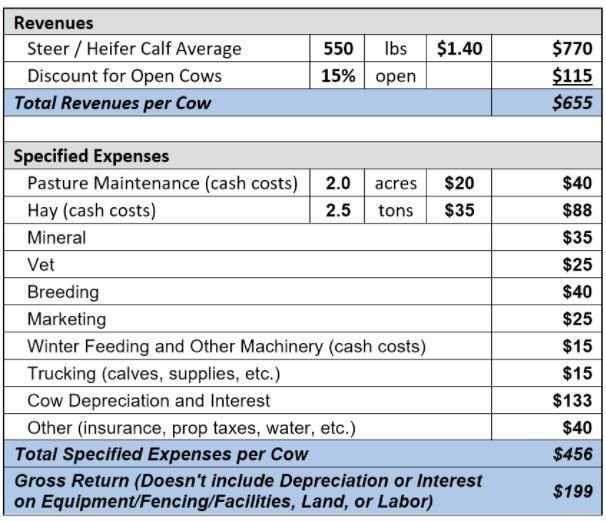

The purpose of this article is to examine cow-calf profitability for a spring calving herd that sold weaned calves in the fall of 2021 and provide an estimate of profitability for the upcoming year. Table 1 summarizes estimated costs for a well-managed spring-calving cowherd for 2021. Every operation is different, so producers should evaluate and modify these estimates to fit their situation. Note that in this table we are not including depreciation or interest on equipment/fencing/facilities, as well as labor and land costs.

Calves are assumed to be weaned and sold at an average weight of 550 lbs. In the fourth quarter of 2021, steers in this weight range were selling for prices in the upper $140’s and heifers in the low $130’s, on a state average basis. Therefore, a steer/heifer average price of $1.40 per lb is used for the analysis, which was $0.10 per lb higher than last year. However, it is important to note that calf prices were much higher in December of 2021, than in October and November. So, the timing of calf sales would have had a significant impact on cow-calf revenues. Weaning rate was estimated at 85%, meaning that it is expected that a calf will be weaned and sold from 85% of the cows that were exposed to the bull. Based on these assumptions and adjusted for the weaning rate, average calf revenue is $655 per cow.

Pasture maintenance costs are assumed to be relatively low at $20 per acre and would include only basic cash costs of pasture clipping (fuel, maintenance, repairs), and a limited amount of reseeding, fertilizer, and fencing repairs. Producers who consistently apply larger amounts of fertilizer to pasture ground would see much higher pasture maintenance costs. The pasture stocking rate is assumed to be 2.0 acres per cow, but producers should carefully consider the stocking rate for their operation, as this will vary greatly. Stocking rate impacts the number of grazing days and winter feeding days for the operation (i.e. high stocking rates will mean more hay feeding days), which has large implications for costs on a per cow basis.

These spring calving cows were assumed to use 2.5 tons of hay per cow, and the estimated cash cost of making this hay (fuel, maintenance, repairs, supplies, fertilizer, etc.) was $35 per ton. Mineral cost is $35 per cow, veterinary / medicine costs $25, trucking costs $15, machinery cash costs for winter feeding and other miscellaneous jobs is $15, and other costs (insurance, property taxes, water, etc.) are $40. Breeding costs are $40 per cow and should include annual depreciation of the bull and bull maintenance costs, spread across the number of cows he services. Marketing costs are currently around $25 per cow, but larger operations may market cattle in larger groups and pay lower commission rates.

Breeding stock depreciation and interest are major costs that are often overlooked. They are generally not cash costs that need to be paid on a yearly basis, unless you have a loan on the cattle, but they are real costs that need to be paid at some point. As an example, assume a bred heifer is valued at $1500, has eight productive years, and has a cull cow value of $700. The average yearly depreciation is calculated as follows:

$1500 bred heifer value

–$700 cull-cow value

$800 total depreciation

$800 depreciation / 8 productive years = $100 cow depreciation per year. The actual depreciation will vary across farms. When buying bred replacement heifers, the initial heifer value is clear. With farm-raised replacements, this cost should be the revenue foregone had the heifer been sold with the other calves, plus all expenses incurred (feed, breeding, pasture rent, etc.) to reach the same reproductive stage as a purchased bred heifer. At an average value of $1100 (halfway between bred heifer and cull value) over her lifespan on your farm, and assuming a 3% interest rate results in a $33/cow/year interest cost, or a total of $133/cow/year in combined depreciation and interest.

Note that based on the assumptions in our example, the total specified expenses per cow are $456 and revenues per cow are $655. Thus, the estimated gross return is $199 per cow. At first glance, this positive return looks impressive but is also misleading. A number of costs were intentionally excluded because they vary greatly across operations. Notice that no depreciation or interest on equipment/fencing/facilities was included. Notice also that labor and land costs were also not included. Thus, the gross return needs to be adjusted by these costs to come up with a true return to the farm.

Table 1: Estimated Gross Return to Spring Calving Cow-Calf Operation

Since these costs vary so much from one operation to the next, it may be helpful to pick a specific sized farm and provide estimates for these costs: a 40-cow operation that is producing its own hay and has all farming operations on its own land (80 acres of pasture and 30 acres of hay).

Assume this farm has on average $50K in equipment which depreciates roughly $1000 every year, or $25/cow/year in depreciation. At 4% interest, an additional cost of $2000 in interest per year, or $50/cow/year, would be realized. Assume also this farm has fencing, barns, working facilities, etc., with an initial value of $50K and a lifespan of 25 years. That would amount to $50/cow/year in depreciation and $25/cow/year in interest.

If we have 2.0 acres of pasture and .75 acres of hayground per cow, and value that at a land rent of $36/acre, that would be $100/cow/year in land rent. Assume also that we have determined we have $100/cow/year in labor, which would amount to $4000 total per year for the entire herd.

Summary of Additional Non-Cash Costs (Example Farm):

Equipment Depreciation $25/cow/year

Equipment Interest $50/cow/year

Fencing-Facilities Depreciation $50/cow/year

Fencing-Facilities Interest $25/cow/year

Land Rent $100/cow/year

Labor $100/cow/year

Total Additional Non-Cash Costs $350/cow/year

These non-cash costs add up to $350/cow/year on our example farm: $150 per cow in depreciation/interest on equipment/fencing/facilities and $200 per cow in land rent and labor. We encourage you to estimate these for your own operation, but the unfortunate reality is that they quickly add up on most farms. The $199/cow/year gross return over cash costs and cow depreciation does not look quite as good now. After adjusting for these other costs, the net return (all costs included) is –$151 per cow per year, or –$6,040 for the 40-cow farm.

Another way to look at this is to just include the depreciation and interest for equipment/fencing/facilities ($150/cow/year), and not include land and labor ($200/cow/year). In this case, the return would increase to $49/cow/year, and would represent the farm's return to land and labor. Did this farm actually lose money on a cash basis? No, not if they are using their own labor and their land is paid for. But the farm also did not make a real profit. This farm essentially paid the equipment/fencing/facilities depreciation and interest in full and part of the labor-land cost. However, the farmer and the land worked for free roughly 3/4 of the time.

These numbers will vary across operations, but estimating your own cost structure is extremely important. Our guess is that compared to our example farm, there are far more cow-calf operations of similar size with a higher cost structure than there are operations with a lower cost structure in Kentucky. Put simply, well-managed spring calving herds were likely covering all cash costs, breeding stock depreciation/interest, and depreciation and interest on equipment/fencing/facilities, but were not generating much of a return on their labor or land this last year.

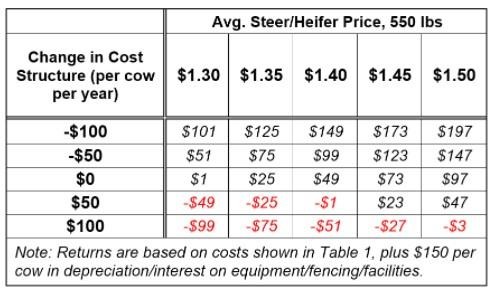

Readers can use Table 2 to modify the analysis based on their cost structure and calf prices for 2021. It uses all costs except for land and labor, so the table shows a return to land and labor.

Table 2: Estimated Return to Land and Labor (per cow) to Spring Calving Cow-Calf

Operation given Changes in Cost Structure and Calf Prices

As an example, we used $1.40/lb in our base scenario as the expected steer/heifer price for 2021. Given the cost structure, we used ($0 change on the left-hand side of the table), the expected return to land and labor is $49/cow/year, just as was previously described. If a cattle farmer also sold their calves for an average price of $1.40/lb, but had a $50/cow/year cheaper cost structure (-$50 change on the left-hand side of the table), their expected return to land and management would increase to $99/cow/year. If another cattle farmer sold their calves for an average price of $1.35/lb calf and had $50/cow/year more expensive cost structure (+$50 on the left-hand side), their expected return to land and management would decrease to -$25/cow/year. In this last example, they had no return to their land and labor and were $25/cow/year short in fully covering all their depreciation and interest expenses.

Predicting cattle prices is nearly impossible given the numerous factors that are likely to impact the market. However, there is good reason to expect higher prices for 2022, and calf prices have already risen quite a bit since last fall. The size of the US cowherd continues to shrink and is actually 5% smaller than it was in 2019. Additionally, beef exports set a record in 2021 and are likely to remain relatively strong this year. Despite high feed prices, 2022 should be the best calf market we have seen since 2015.

Given that, our best guess for fall 2022 prices for that same 550 lb steer/heifer are in the $1.50-1.60/lb range. Spring prices are likely to be much higher than this, but we do expect calf prices to decline seasonally by fall. At a $1.55/lb price, and using the same cost structure as in 2021, the return to land and labor would now be estimated at $119/cow/year. This would compensate a cow-calf operator for about 60% of the value of their labor and land cost, which would be a considerable improvement over 2021. However, fertilizer costs have increased exponentially in the last year, and will significantly reduce profitability on those cattle farms that rely heavily on commercial fertilizer.

For an acre of hay fertilized at 60 units N, 30 units Phosphorous (P2O5), and 100 units Potassium (K2O), this would increase the overall cost from $67 to $144 per acre, an increase of $77 per acre. For an acre of pasture fertilized at 60 units N, 10 units Phosphorous (P2O5), and 33 units Potassium (K2O), this would increase the overall cost from $38 to $87 per acre, an increase of $49 per acre. If we assume one acre of hay and two acres of pasture needed per cow, this would amount to a $175 increased cost for every cow in the herd. Thus at that same average steer/heifer price of $1.55/lb, the return to land and labor estimated at $119/cow/year with the 2021 cost-structure, would sink to -$56/cow/year. The cattle farmer and the land would now be working for free again, as well as being $56 short in fully covering depreciation and interest costs. Managing around these high fertilizer prices will be the paramount challenge in 2022 and potentially beyond. For details of the fertilizer price increases as well as practical strategies to reduce or eliminate fertilizer use on cattle farms see the accompanying article this month “Reducing Your Dependency on Commercial Fertilizers - Strategies for Cattle Farms in 2022 and Beyond”.

In the spring of 2021, the authors of this article partnered with the Kentucky Beef Network to offer a webinar series entitled, Managing Cow-calf Operations for PROFIT. Over the course of three evenings, a large number of topics were discussed that aimed at improving the profitability of cow-calf operations. Videos and materials from each session are available to read and download.

Source : osu.edu