By Jeff Martin

While bison are often thought of as quintessential grazers, their diet is surprisingly variable. However, they also snack on non-grass species throughout the year. The sheer variety of vegetation they consume is both impressive and dynamic throughout the growing and non-growing seasons. Two recent studies, Craine (2021) and Hecker and colleagues (2021), document bison diets using a few techniques, providing valuable insights for management and conservation.

Methods for Studying Bison Diets

Scientists use a combination of techniques to determine what bison eat. One powerful tool is eDNA (environmental DNA). By analyzing bison fecal materials, researchers can extract and sequence DNA fragments, identifying the specific plant species the bison consumed – even those that are quickly digested. This is valuable because some species are highly digestible and leave no physical remains behind for visual identification, especially early in the growing season. However, eDNA doesn't quantify the amount of each plant eaten.

For that, researchers use techniques like microhistology (microscopic examination of plant fragments in processed fecal or rumen matter). This technique is labor-intensive and requires expert knowledge, but it allows for volume correction, which is necessary to fully understand how much biomass of each forage species was consumed. Combining these techniques gives a more comprehensive picture.

Case Study 1: Seasonal Diet Variety using eDNA

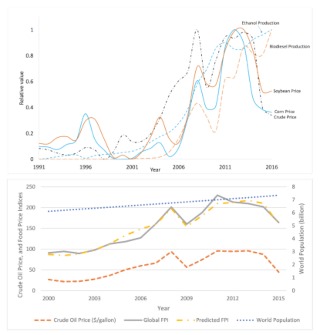

Craine (2021) used eDNA to investigate the seasonal patterns of bison diet across climate gradients, analyzing data from 45 bison herds across the contiguous U.S. in 2019. The study revealed that bison diets change through the growing year, likely responding to what is available.

- Cool-season (C3) grasses (grasses that grow best in cooler temperatures) comprised at least 20% of the species identified in bison diets, with a higher proportion during the early growing season.

- Warm-season (C4) grasses (grasses that thrive in warmer temperatures) made up no more than 10% of the species consumed.

- Forbs (broadleaf, non-woody flowering plants), both leguminous (nitrogen-fixing, like clover, purple prairie coneflower, and lupine) and non-leguminous (like asters), constituted well over 50% of the species consumed, with an even higher proportion later in the growing season.

- Browse and other species include leaves and twigs and other woody material that is neither a grass nor a forb.

In essence, bison consume a widely variable diet, with a greater proportion of cool-season grasses (C3) and non-legume forbs early in the growing season, shifting towards more warm-season grasses (C4) and leguminous forbs later on. These findings have important implications for understanding what bison are selecting across a variety of plant communities throughout the year.

Case Study 2: Diet Composition by Volume using Microhistology and Observation

Hecker and colleagues (2021) focused on diet composition by volume, using techniques like microhistology to analyze data from 16 herds across the U.S. and Canada. Their research found that bison diet composition by volume averages nearly 91% grasses, even though the variety of grass species is less than 50% of the total diet. This highlights that, while bison consume a variety of plants, grasses provide the majority of their dietary intake and comprise the main source of their energy (carbohydrates), fats (lipids), and proteins.

Figure 2. Bar charts comparing the results of different methods used to analyze bison diets. (left) Shows the percentage of the diet made up of each functional forage plant group. (right) Shows the percentage of macronutrient constituents as determined by sampling technique. Metabolizable energy is the energy available to the bison after accounting for losses during digestion. The key difference between the methods is that DNA (environmental DNA analysis of dung) identifies the presence of plant species, while microhistology (microscopic examination of plant fragments in dung) and other traditional methods allow for estimation of the volume of each plant type consumed. This figure highlights that while eDNA may reveal a high variety of forbs in the diet, methods that quantify the amount of each plant type consumed show that grasses are the dominant component of the bison diet in terms of both bulk and energy contribution. Adapted from figure 6 and data in Hecker et al. 2021.

Conclusion

The studies by Craine (2021) and Hecker and colleagues (2021) demonstrate that bison diets are characterized by both a surprisingly high variety of plant species and a strong reliance on grasses for the majority of their nutritional needs. The combination of eDNA and traditional methods provides a more complete picture of bison dietary preferences and their seasonal variations. Importantly, when these techniques are used together, we gain a more complete understanding of how bison grazing and dietary selection contribute to plant variety and landscape heterogeneity. While bison may select forbs (leguminous and non-leguminous), they consume relatively small amounts, which can stimulate forb growth and allow these plants to reach maturity and reseed, ensuring their presence in the following year.

Source : sdstate.edu