By Jenna Falor

If you are a wheat farmer, especially if you have soft white wheat, at one point or another you have probably received a discount at the elevator after delivering wheat. But what exactly does a falling numbers test measure and why does it matter?

What is going on with wheat after maturity in the field?

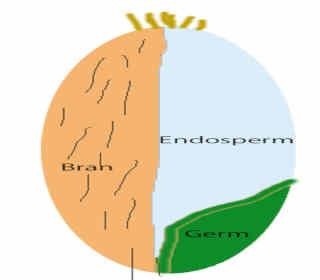

A wheat seed at physiological maturity is typically 83% endosperm (this is what makes up white flour), 14.5% bran (which can be used in whole wheat flower) and 2.5% germ. The physical makeup of endosperm is approximately 80% starch, 10% protein and 10% other.

Frequent rainfall during wheat harvest can cause seed to absorb water, the initial step in germination. When this occurs in an unharvested wheat crop, also known as preharvest sprout, the physiological makeup of that seed begins to change. A protein called alpha-amylase is produced. This then starts turning the starch in that endo-sperm into simpler carbohydrates such as sugar to feed the sprout. The germination process not only changes the production of alpha-amylase but also of other hormones. The increase in proteolytic activity during preharvest sprout causes protein degradation to occur, which includes gluten, which is key in bread structure.

How is a falling number tested and what does it mean?

A falling number test estimates the amount of preharvest sprout that has occurred in the grain while still in the field. This is tested at the elevator by grinding a sample and then making a slurry of the flour and water. A plunger is then put in and it measures how long it takes for the plunger to fall to the bottom of the test tube. For wheat, a typical range would be 300-400, though the rejection point for any elevator may be higher based on the specs of mill they are shipping to. The higher the falling number means it takes longer for the plunger to fall. A low falling number indicates the enzymatic process of the starch breaking down has begun to occur. So, the lower the number, the more enzymatic activity has occurred, causing the starch to break down.

Why does it matter?

Wheat flour is typically used in baking, among other things. This means that starch balance is crucial. If seed has started to convert the starches into more simple carbohydrates like glucose, which occurs during preharvest sprout, this can cause issues when baking by disrupting the fermentation process, causing issues with rise and overall quality. Mills can blend wheat with varying falling number levels to obtain the overall balance they want per batch. This cannot typically be done by a farmer because it takes such a large quantity of high-quality wheat to blend with low falling numbers, as little as 5% of wheat having low falling numbers can drastically affect results.

What causes low falling numbers?

There are two main causes of low falling numbers. The first is preharvest sprout, which is typically caused by cool, rainy weather after the wheat has turned gold. This is the one that farmers usually think of because you can see the physical damage to the wheat as it progresses. The second is the presence of late maturity alpha-amylase caused by large temperature swings during the grain maturation phase.

While the environment plays are large role, genetics are also involved. Some varieties are more susceptible to low falling numbers. One example of genetics playing a role is soft red winter wheat, which has been shown to have fewer issues with low falling numbers than soft white winter wheat. In the Michigan State University variety trials for 2021 and 2022, the preharvest sprout rating (0-9 with 0 being better) for red winter wheat averaged 2.0 versus 5.9 for white winter wheat.

Why is there so much variability in falling numbers?

There are a number of reasons why falling numbers can be variable even within a single field. The first reason goes back to the weather. There are different microclimates within fields that can cause variability in preharvest sprout. The next two reasons are human: since the sample size is so small it can be hard to get a completely representative sample and there is variability within the testing procedure itself.

This article was published by Michigan State University Extension. For more information, visit https://extension.msu.edu. To have a digest of information delivered straight to your email inbox, visit https://extension.msu.edu/newsletters. To contact an expert in your area, visit https://extension.msu.edu/experts, or call 888-MSUE4MI (888-678-3464).

Source : msu.edu