By Dan Undersander and Craig Saxe

How does forage dry?

If we understand and use the biology and physics of forage drying, not only does the hay or haylage dry faster and have less chance of being rained on, but the total digestible nutrients (TDN) of the harvested forage are higher. As mowing and conditioning equipment has evolved, some of the basic drying principles of forage have slipped by the wayside and we need to review them.

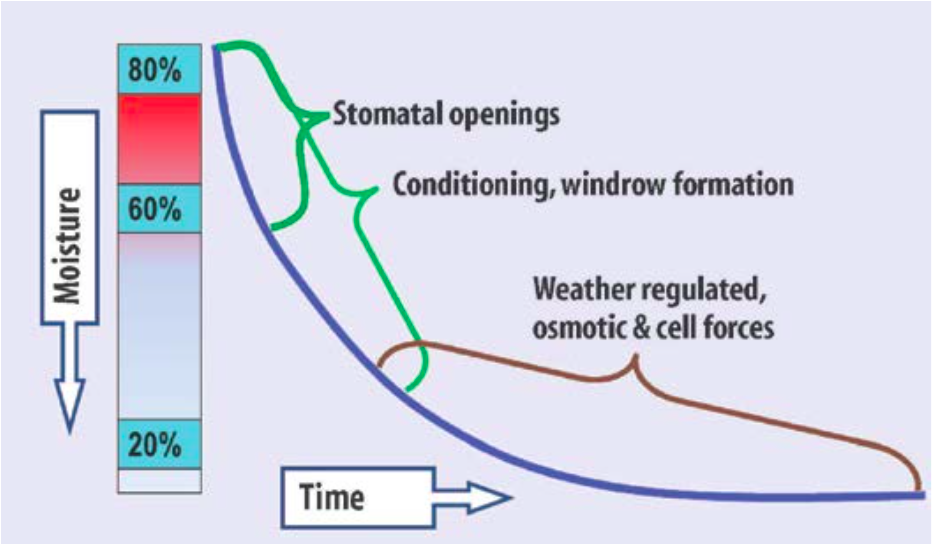

The general pattern of drying forages is shown in the figure at right. When forage is cut, it has 75 to 80 percent moisture that must be dried down to 60 to 65% moisture content for haylage and down to 14 to 18% moisture content for hay (lower figures for larger bales).

The first phase of drying is moisture loss from the leaves through the stomata. Stomata are the openings in the leaf surface that allow moisture evaporation from the plant to cool it and carbon dioxide uptake from the air as the plant is growing. Stomata open in daylight and close when in dark and when moisture stress is severe. Cut forage laid in a wide swath maximizes the amount of forage exposed to sunlight. This keeps more stomata open and encourages rapid drying which is crucial at this stage because plant respiration continues after the plant is cut. Respiration rate is highest at cutting and gradually declines until plant moisture content has fallen below 60%. Therefore, rapid initial drying to lose the first 15% moisture will reduce loss of starches and sugars and preserve more total digestible nutrients in the harvested forage. This initial moisture loss is not affected by conditioning.

The second phase of drying is moisture loss from both the leaf surface (stomata have closed) and from the stem. At this stage conditioning can help increase drying rate, especially as the forage becomes drier.

The final phase of drying is the loss of tightly held water, particularly from the stems. Conditioning is critical to enhance drying during this phase. Conditioning to break stems every two inches or scrape the waxy cuticle off will increase water loss through the waxy cuticle of the stem.

How does swath width influence drying rate?

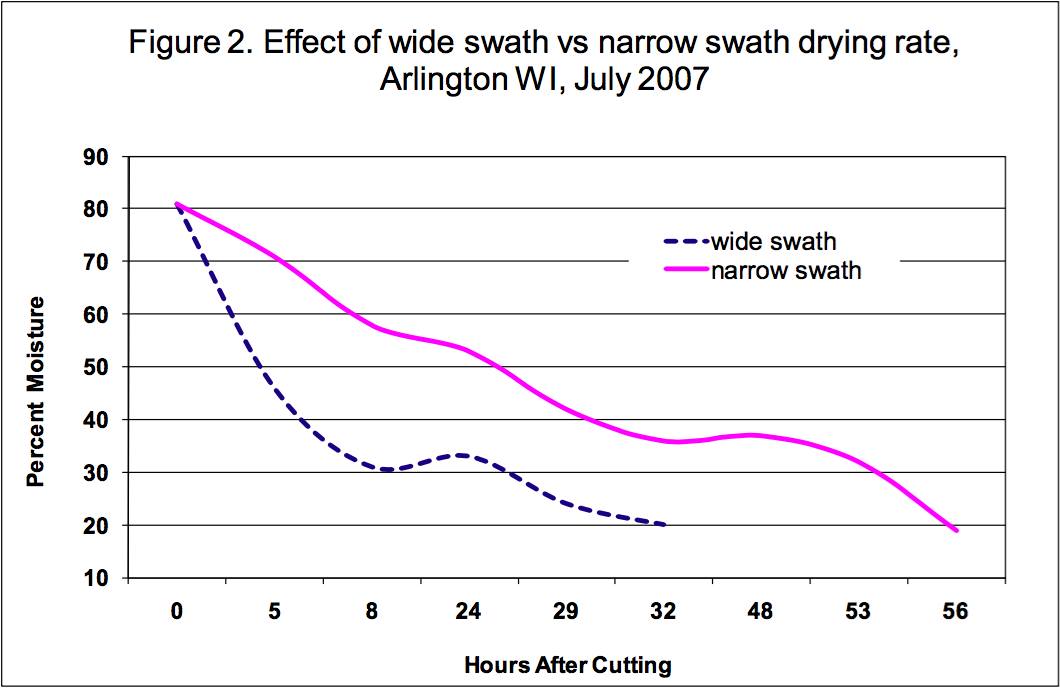

Understanding these principles will allow us to develop management practices in the field that maximize drying rate and TON of the harvested forage. The first concept is that a wide swath immediately after cutting is the single most important factor maximizing initial drying rate and preserving of starches and sugars. In a trial at the UW Arlington Research Station (Figure 2) where alfalfa was put into a wide swath (covering >70% of cut area) it reached 65% moisture in about 8 hours and could be harvested for haylage the same day as cutting. The same forage from the same fields put into a narrow windrow (covering approximately 30% of cut area) was not ready to be harvested until late in the day or the next day!

In fact, a wide swath may be more important than conditioning for haylage.

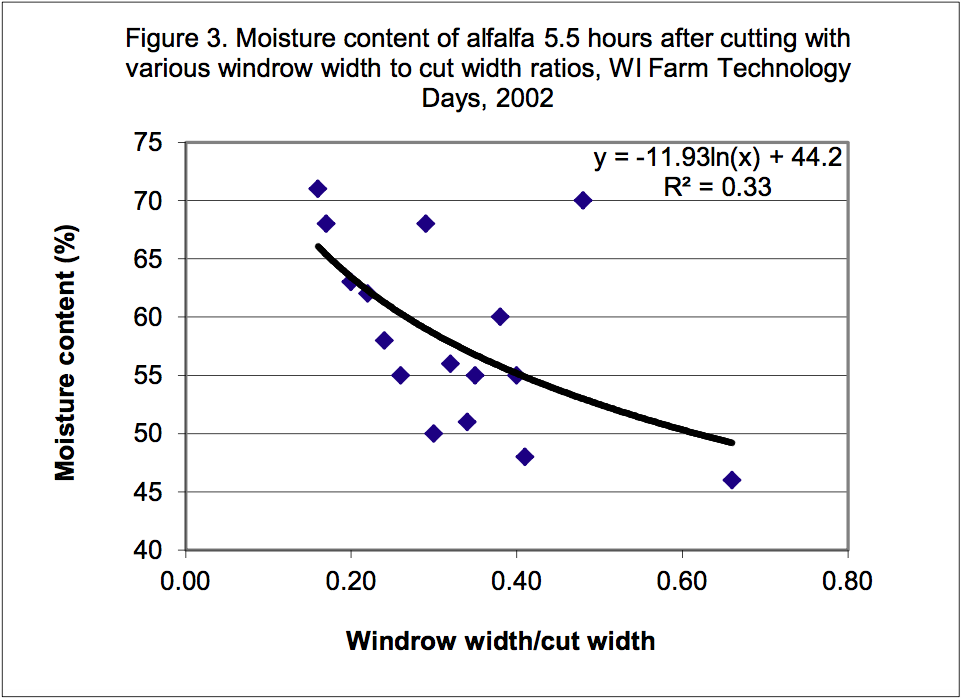

The importance of a wide swath is supported from drying measurements taken at the Wisconsin Farm Technology Days in 2002 (figure 3) where different mower-conditioners mowed and conditioned strips of alfalfa and put the cut forage in windrow widths of the operators choice. Moisture content of the alfalfa was measured 5.5 hours after mowing. Each point is a different machine that included sickle bar and disc mowers and conditioners with steel, rubber or combina- tion rollers. Across all mower types and designs, the most significant factor in drying rate was the width of the windrow.

In figure 3, note the one outlying point at 70% moisture content and a windrow width/cut width ratio of 0.48. This shows how much drying can be slowed by improper adjustment of the conditioner.

Many farmers have gradually gone to making windrows that are smaller percentages of the cut area as mowers have increased in size. Generally, the conditioner has stayed the same size as mower cutting bars have gotten bigger, resulting in narrower windrows. There is some variation among makes and models and growers should look for those machines that make the widest swath.

Does swath width influence forage quality?

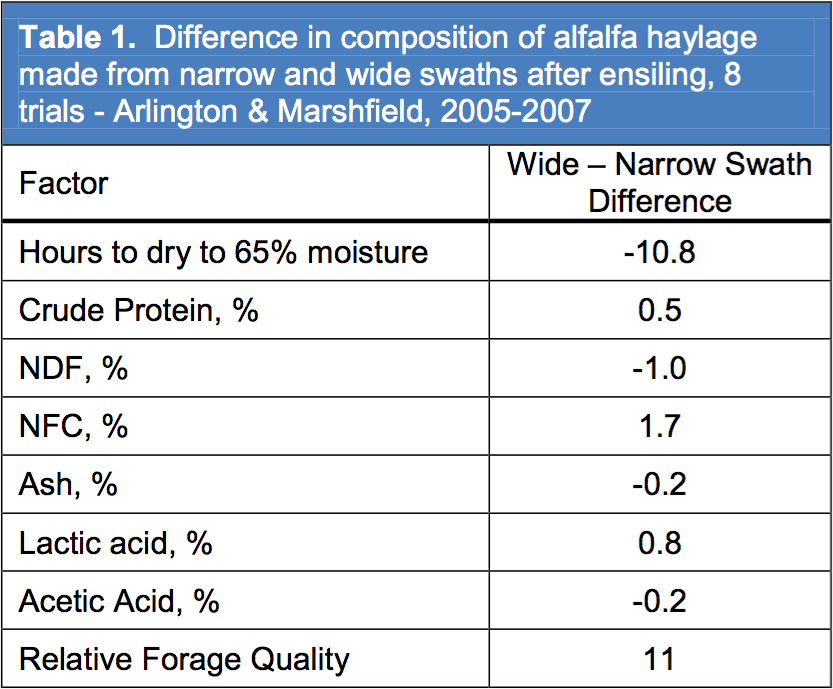

Putting alfalfa into wide swaths (72% of cut width) immediately after cutting often results in improved quality of alfalfa haylage compared to narrow windrows (25% of cut width) in studies at UW Arlington and Marshfield Research Stations in 2005 to 2007 (Table 1 ). Alfalfa was mowed with a discbine, conditioned, and haylage was sampled approximately two months after ensiling in tubes. The alfalfa from the wide swaths had 1.0% less NDF, and 1.7% more NFC. Haylage from the wide swath had more substrate for fermentation which resulted in more lactic and acetic acid. The higher acid content would indicate less rapid spoilage on feedout.

A wide swath requires that one or both tractor wheels drive over the swath. While this may not be desirable, it results in less loss than making a narrow windrow. The reduced drying of the wide swath with a driven-over portion is less than if a narrow windrow is made. Also, as table 1 shows, the ash content of haulage from wide swath alfalfa was actually less than from narrow windrows with no wheel track. Narrow windrows tend to settle to the ground causing soil to be included with the bottom of the windrow when it is picked up. Wide swaths tend to lay on top of the cut stubble staying off the ground. Driving on the swath can be minimized by driving one wheel on the area between swaths if swath covers less than the full cut width.

Grasses, especially if no stems are present, must be laid into a wide swath when cut. They generally must also be tedded about 24 hours after cutting and then raked into a windrow later. Grass forage, when put into a windrow at cutting, will settle together, dry very slowly and be difficult to loosen up to increase drying rates.

Recommendations

- Cut at the proper height – 2 to 4 inches for alfalfa and 3 to 4 inches for grass or legume/grass mixtures.

- Adjust conditioner properly. Roller conditioners are best for alfalfa due to reduced leaf loss. Either type, if properly adjusted (1 to 5% of leaves show some bruising), will cause drying at a similar rate.

- Lay hay in a wide swath covering 70% or more of the cut area to enhance rapid drying.

- Rake/merge ahead of chopping or at a moisture content that minimizes leaf loss for hay (40 to 60% moisture – often reached 24 hours after mowing).

Source:uwex.edu