By Nathan Briggs and Ronald P. Lemenager

Introduction

A challenge that beef and dairy producers manage through during the wet season is mud, which can deteriorate areas of heavy use (Figure 1). Some of these areas can be found around bale feeders, waterers, feed bunks, gateways, and/or alleyways. Mud is a combination of soil, manure, and urine. Cow comfort and health will be decreased when exposed to pathogen enriched mud. Unhealthy or uncomfortable cows do not have the growth rate or milk production of healthy cows. Cattle that are exposed to muddy environments have decreased efficiency, which includes muscle or fat deposition in feedlot cattle or milk production in lactating cows. If the cows are producing less milk, then the calves will have lower weaning weights. The economic inefficiencies will come from animal temperature imbalances or activated immune systems, requiring energy to be used for maintenance rather than for production purposes. A wet hair coat caused by mud along with the cooler temperature during the Northeast wet season will increase the animal’s environmental heat loss. This will then lead to an increased maintenance energy need and cause a decrease in production and efficiency.

Figure 1

In addition to the economic challenges, rainwater can mix with manure, urine, and sediment, which can cause runoff into water sources. When excess nutrients enter into water sources, algae utilize the nutrients, which result in algal blooms (Figure 2). Fish and other aquatic life struggle to survive in algal blooms, because the algae produces toxins and decreases oxygen that can kill fish and the rest of the aquaculture ecosystem according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The detrimental effects of the algal blooms can impact the county and national economies.

Figure 2

Heavy use areas with livestock are inevitable, but some structures can be used to help limit the amount of runoff that enters into sources of water. The Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) defines a heavy use area as “all areas where livestock congregate and cause surface stability problems.” Provisions should be designed and implemented to collect, store, utilize and/or treat the contaminated runoff from the area. There are many types of changes that can be implemented in high traffic areas to help mitigate the mud.

One durable technique is to pour a concrete pad, redirect any ‘clean’ water flow around the pad, and redirect pad runoff towards dense vegetation. This vegetation will help in the absorption of water pollutants, so water sources stay clean and prevent algal blooms. The issue with this method is the relatively high cost of concrete.

Alternatively, a method using geotextile fabric and gravel can be used to reconstruct the heavy use area, which is less expensive than concrete. This method will require maintenance every few years but is a feasible solution to muddy areas. Vegetation should still be at the edges of the pad to absorb water and potential water pollutants. The ease in constructing the pad, in addition to the lesser price, makes the gravel heavy use area pad an attractive solution to improve animal efficiency and the environment.

Construction: Layout

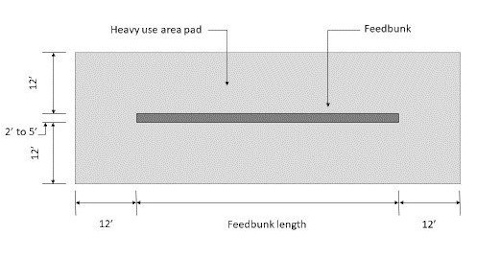

Heavy use area pads should cover all high traffic areas. The pad should extend 12 ft. from the edge of the object of interest that causes high traffic (feeder, water, etc.). If multiple feeders are used, then add to the length of the pad to ensure that it extends 12 ft. past the feeders on either end (Figure 3 and 4). A slight slope (1/4 in. per 1 ft.) should be incorporated into the pad to prevent water from puddling on the pad, but not too steep that the slope causes erosion within the heavy use area pad. If building on a slope, the entire pad should be leveled to ensure that water does not channel and increase erosion. ‘Clean’ water from the high side of the pad should be diverted around the pad. Any place that mud builds up will be an ideal location for a heavy use area pad. If the pad is a winter feeding pad, then plan how to minimize additional mud spots caused by equipment when delivering feed or hay. This can be accomplished by not driving through low points in a field or by building a pathway to the feeding area. Figures 3 and 4 are the construction guidelines for a heavy use area pad.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Construction: Excavation

Once the area of the pad has been determined, the first step in the project is to remove the sod and soft soil (organic matter, mud, etc.) in the desired location. If the desired location is muddy, all mud will need to be removed down to a solid surface. Choose a different location if the location is extremely muddy. The goal is to take a couple inches off. If the area is excavated too deeply, the pad could act like a French drain or a pond, which will harbor water in the area and eventually become problematic. The final pad should be higher than the grass surrounding it. Any removed soil can be utilized to fix any other water flow issues on the farm or to divert water around the pad if it is constructed on a slope.

Construction: Geotextile Fabrics

Geotextile fabrics are commonly used on road construction projects to help secure soil and stone from moving. In this project, the fabric will be used to separate the rock layers from the soil. Without geotextile fabric, time will cause stone and soil to mix and longevity of the pad will decrease. Any water that permeates the pad will eventually reach the soil, turn to mud, and seep up through the stone, which can cause the muddy area to reoccur.

There are two different types of geotextile fabric, woven and nonwoven. Woven geotextile is commonly used in landscaping to prevent weed growth. Alternatively, nonwoven geotextile will work better for this project, because the rocks interlock and create a strong base. A variety of thicknesses are available for geotextile fabric. The NRCS recommends using a minimum thickness of 6 oz/yd2, but 8-10 oz is ideal if the pad will be driven over. A local NRCS conservationist can help select the proper geotextile fabric, if questions arise.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Geogrid is a plastic grid (similar to snow drift fencing) that can be used in extremely heavy traffic areas, or if the pad is commonly subjected to concentrated heavy loads. This could be an option for areas commonly driven over with a tractor or skid steer.

The geotextile fabric commonly comes in widths of 12-15 ft., and it can be rolled over the entire area that has been excavated. Allow for 2 ft. of overlap for large areas that require multiple pieces of geotextile. The fabric should be secured with large nails or stakes, as shown in Figure 7, to prevent movement for the rest of the construction.

Figure 7

Construction: Coarsely Crushed Stone Layer

The base aggregate will be coarser to help make a solid foundation for the pad. Commonly the aggregate that is used to create the base is #53 or #57 stone, because there are multiple sizes of stone that interlock well (Figure 8). The geotextile fabric replaces #2 stone in creating a solid base. A #7 or #8 stone is less than ideal, because the stones will be able to roll around. Sand is not ideal, because sand will move around and not produce the firm base that is needed. Crushed limestone should be used instead of round aggregates, because crushed stone has many different angles to the stone that will interlock together better. The round aggregates will be able to move around, and fail to create the solid foundation that is required for the project.

The heavy use area pad should have 6-8 inches of coarse aggregate on top of the geotextile fabric. If the pad is used heavily or has equipment commonly driven over it, then 8 inches will work best. If more than 6 inches of coarse aggregate is used it should be applied in multiply lifts/layers. The coarse aggregate should be compacted down to create a firm base before adding the finely crushed stone layer.

Figure 8

Construction: Finely Crushed Stone Layer

The final aggregate that should be added to the pad is a finely crushed stone layer. Coarse ag lime or lime screenings will work for this step (Figure 9). Make sure to use a coarse ag lime, rather than normal ag lime, because the lime spread on fields is too fine that the top layer will potentially blow away in the wind. When scraping the pad, the fine layer will aid in knowing how deeply one is scraping the pad. Finely crushed stone in the manure are small enough that manure can be spread on the field or pasture without causing any issues.

At least 2 inches of fine aggregate depth should be used to start. With time, the aggregate will settle down into the more coarse aggregate due to the rain and traffic, providing a more durable surface. The final layer should have a crown to it, so the water will shed off in all directions. This crown is important to prevent erosion and increase the longevity of the pad.

Figure 9

Maintenance:

Maintenance should not need to be done for 3-5 years after construction of the pad. This depends on how often and well the pad is scraped and how often it is used. Replacing the fine aggregate to the top of the pad should be the only maintenance that is required. If the pad is constructed, cleaned well, and maintained, the coarse aggregate layer should not need to be replaced. Water or loader buckets scraping too deeply can cause damage to the coarse aggregate, causing pad integrity issues.

Conclusion:

Heavy use area pads make animals more efficient by keeping them clean and dry. Producers do not want to sacrifice efficiency, because that is not economical. In addition, waterways will be cleaner, because less manure will erode into streams. This combination of benefits to producers and the environment will allow producers to be more sustainable on the land that they have. Contact your regional NRCS for technical help or assistance.

Source : psu.edu