By Daniel Munch

Foreign investment in U.S. agricultural land is a hot topic, largely spurred by media reports raising concerns about bad actors from adversarial nations purchasing land for potentially hostile purposes. For most, understanding of the formal processes for reviewing foreign investments and tracking existing ownership dynamics is limited. Under the authorities granted to it by the Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act of 1978 (AFIDA), USDA is required to track information pertaining to foreign ownership of U.S. agricultural land. Successful monitoring of investments and enforcement of the law by USDA, however, has been challenging and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently released recommendations outlining how USDA can improve their data collection and processes. A deep dive into AFIDA and the data available can be reviewed in a previous article: Foreign Investment in U.S. Ag Land – The Latest Numbers.

Though USDA plays an important role in tracking foreign-owned farm, ranch and forest land, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is the primary entity authorized to review and potentially block transactions involving foreign investment. Farm bill frameworks released by both Senate and House Agriculture committees include specifications related to improving AFIDA and bolstering the effectiveness of CFIUS. Today's article describes the CFIUS process and highlights the recent upward trend in the number of actions the committee has been tasked with reviewing.

History

CFIUS traces back to concerns during the Cold War, when foreign investments, particularly from adversarial nations, began raising alarms about potential threats to U.S. national security. In response, President Gerald Ford issued Executive Order 11858 in 1975, establishing CFIUS to monitor and evaluate the impact of foreign investments. Initially, CFIUS had limited authority and acted primarily as an advisory body, often to dissuade Congress from enacting burdensome restrictions that could hinder U.S. economic growth. Original interagency members included representatives from the departments of State, Defense, Treasury and Commerce, and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. The executive office of the president also had representation.

As the geopolitical landscape evolved over the following decades, so did the nature of foreign investments. High-profile acquisitions by foreign entities, such as the Japanese purchase of significant American assets in the semiconductor, telecommunications and automotive industries in the 1980s, prompted Congress to enhance CFIUS' powers. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 included the Exon-Florio amendment, which granted the president of the United States the authority to block or unwind foreign acquisitions, mergers or takeovers of U.S. companies if current laws were inadequate to protect national security in the situation and there was credible evidence that the foreign investment could impair national security. This power was utilized in 1990 when the Bush administration directed China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation to divest acquisition of Mamco Manufacturing Inc., a Seattle-based firm producing metal parts and assemblies for aircraft.

Post-9/11, the security paradigm shifted again, and the Foreign Investment and National Security Act (FINSA) of 2007 further strengthened CFIUS. FINSA provided statutory authority to many of the committee's practices and required more rigorous reporting to Congress, reflecting the increasing complexity and importance of national security considerations in foreign investment reviews. FINSA also added the secretaries of Energy and Labor and director of national intelligence as ex officio members.

Regulations released in 2008 created a voluntary system of notification by parties to an acquisition and allowed for notices by agencies that are members of CFIUS. Entities that potentially fall under CFIUS’ jurisdiction and do not voluntarily notify the committee remain indefinitely subject to possible divestment or actions by the president. This incentivizes entities to voluntarily notify the committee of investment actions for a form of immunity to future CFIUS review.

In 2018, Congress and the Trump administration enacted the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) to address growing concerns about national security risks posed by foreign investments in critical U.S. industries and technologies, which can include significant agricultural assets. FIRRMA significantly expanded CFIUS' authority and resources, allowing it to review a broader range of transactions, including non-controlling investments and real estate transactions near sensitive sites. It introduced mandatory reporting requirements for some transactions involving critical technologies and established clearer timelines and procedures for reviews. Mandatory declarations are required if a foreign person has a “substantial interest” in a U.S. business and a foreign government holds a “substantial interest” in the foreign entity making the investment. The regulations define “substantial interest” as a voting power threshold of 25% between a foreign person and a U.S. business and 49% or greater between a foreign government and foreign person.

The Review Process

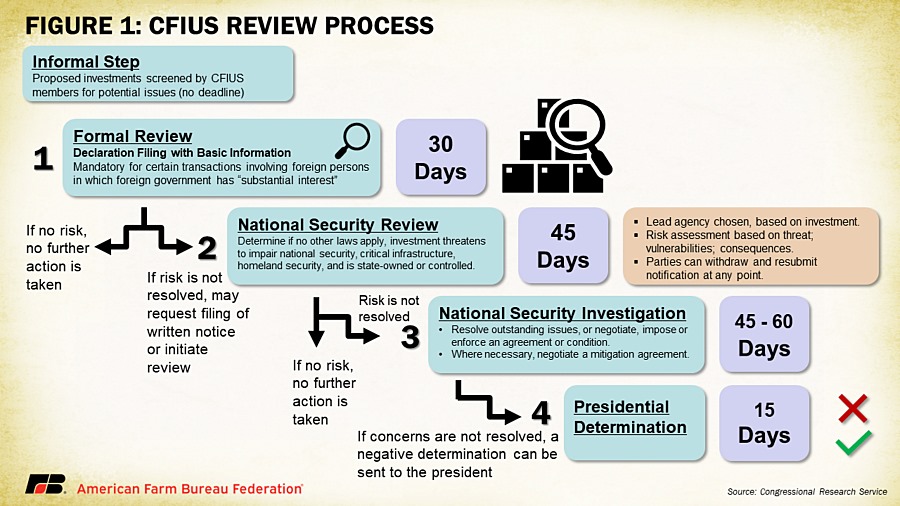

CFIUS has the power to review transactions, whether they are pending or already completed, even if the involved parties did not voluntarily file for review. This can occur, informally, if a committee member believes the transaction falls under CFIUS' jurisdiction and might present national security concerns. The formal CFIUS review process begins when parties submit a notice or declaration regarding a foreign investment in a U.S. business. CFIUS has 30 days to review a declaration or written notification to determine if a transaction involves a foreign person in which a foreign government has a substantial interest. If any risk is revealed, a 45-day review period is initiated, during which CFIUS examines the transaction for potential national security risks. If further concerns are identified, a 45-day investigation phase is launched. This phase can be extended up to 60 days under “extraordinary circumstances.” If the transaction is deemed a threat to national security, CFIUS may negotiate a mitigation agreement that is imposed as a requirement for approval for the investment or recommend the president block or unwind the deal. If unresolved risks persist, the president has an additional 15 days to decide on the transaction. Throughout the 135–150-day process, CFIUS communicates with the involved parties, requesting necessary information and updates to ensure a comprehensive assessment.

Trends in CFIUS Reviews and Notifications

Under FINSA starting in 2008, CFIUS is required to release annual reports to Congress to enhance transparency and accountability regarding its activities. These reports include detailed information on the transactions reviewed, national security concerns identified, and measures taken to mitigate those concerns. The latest report available covers transactions reviewed up until and through 2022.

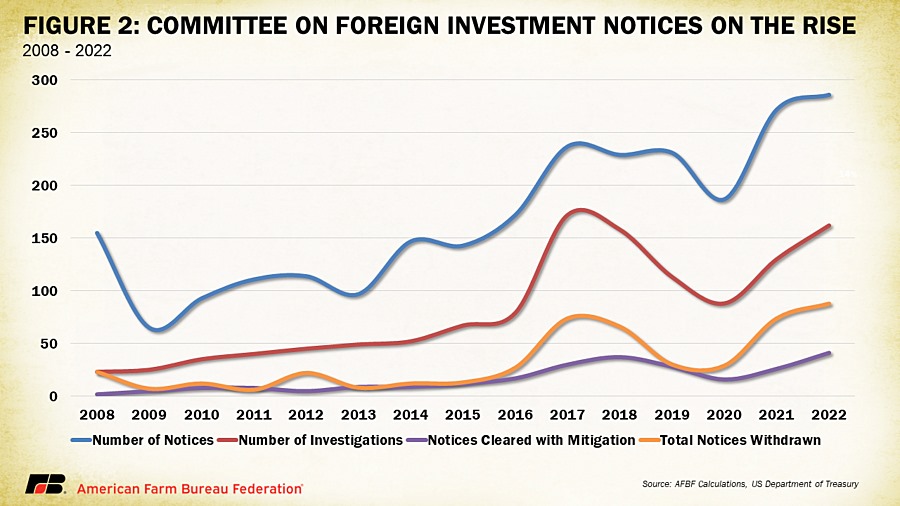

In 2022, CFIUS reviewed 286 notices, a 5% increase from 272 in 2021 but 131 (84%) more than in 2008. The committee conducted investigations for 162 of these notices, which was up 25% from 2021 when they conducted 130 investigations. This is seven times higher than in 2008 when the committee conducted just 23 investigations. The percentage of notices formally investigated has increased from a low of 14% in 2008 to 56% in 2022. The highest percentage of notices investigated occurred under the Trump administration in 2017 when nearly 73% of all notices were investigated by CFIUS. There also has been a notable increase in the number of mitigation measures imposed, with 52 instances in 2022 compared to 31 in 2021 and just two in 2008, indicating a more aggressive stance on mitigating potential security threats. In general, CFIUS has received more notices, conducted more investigations and put in place more mitigation agreements in recent years as compared to when reporting began in 2008 (Figure 2). The number of notices withdrawn has also increased substantially. Notifying parties may withdraw a notification if they need more time to provide details to address CFIUS’ concerns, they would like to restructure the deal to alleviate concerns or they believe concerns cannot be resolved and do not want to be blocked in a presidential decision (which can be very public in nature).

The 2022 report also noted that Singapore was the most frequent country of origin for filed notices, followed by China and the United Kingdom. The number of filings from Chinese investors decreased, possibly due to heightened U.S.-China geopolitical tensions and increased scrutiny of such investments.

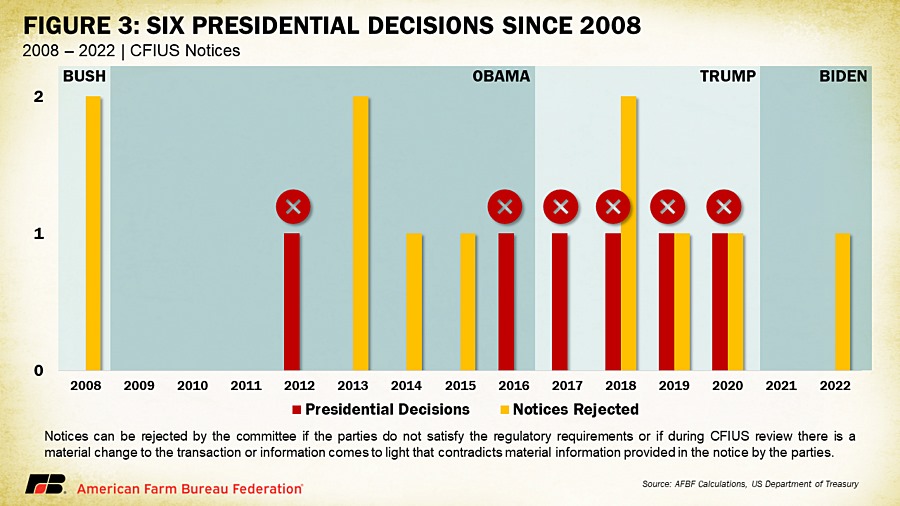

Notably, there have been only six presidential decisions since 2008 and all six resulted in a block. Combined with the block by President Bush in 1990, a presidential decision to block a transaction under CFIUS has only occurred seven times. That said, the rigorous review process, pressure to comply and the public nature of the process incentivize investors to resolve concerns or withdraw their investment before reaching the president. Notices may also be rejected by CFIUS if they do not satisfy the requirements or there is a material change that contradicts information provided in the notice. Presidential decisions and notices rejected by presidential administrations are displayed in Figure 3.

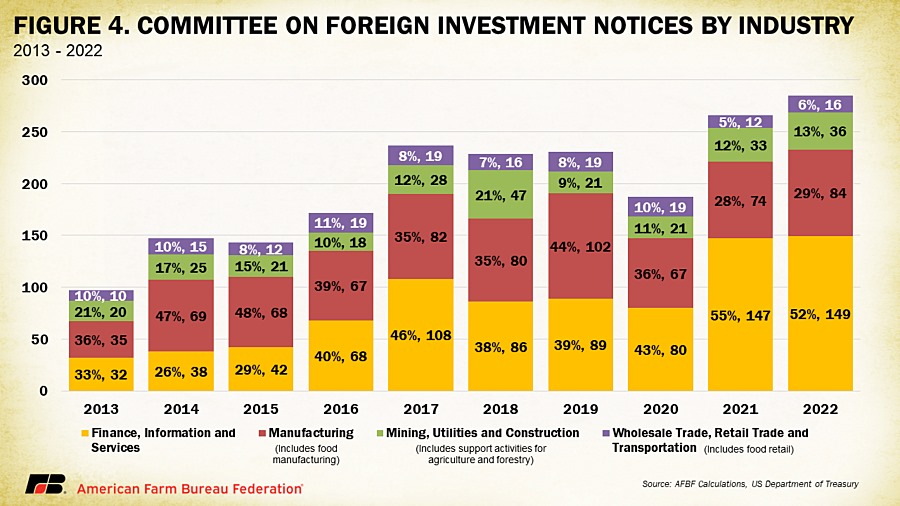

In its annual reports to Congress, CFIUS also reports on notices by industry sector. In 2022, the finance, information and services sector accounted for 52%, or 149 of the 286 CFIUS notifications. Professional, scientific and technical services was the largest subsector, accounting for 44% of the sector’s notifications. Telecommunications followed with 22 notices.

In 2022, the manufacturing sector accounted for 29%, or 84 of the 286 CFIUS notifications. Computer and electronic manufacturing accounted for 37% of all manufacturing notices, with the next-largest subsector accounting for 17%. Food manufacturing is included in this sector, but no food manufacturing notices occurred in 2022 or 2021.

Mining, utilities and construction had the third-largest segment of notifications at 13%, or 36 of the 286 CFIUS notifications. The utilities subsector accounted for 67% of this sector, followed by support activities for agriculture and forestry subsector, oil and gas extraction subsector and specialty trade contractors subsector, all of which had three notices each.

Finally, the wholesale trade, retail trade and transportation sector accounted for 6%, or 16 of the 286 CFIUS notifications, in 2022. Support activities for transportation was the largest subsector in this category with 44% of the sector’s total. It was followed by merchant wholesalers and durable goods with 31% of the sector’s total (which includes food retail). Between 2020 and 2022 only seven notices have come from food manufacturing, retail or support for agriculture and forestry industries.

Click here to see more...