By Romulo Lollato

The sudden sharp drop in temperatures across Kansas this week will cause the wheat crop to go into dormancy. Whether it will injure the wheat to any degree depends on several factors which are described in more detail in this article.

Topsoil moisture

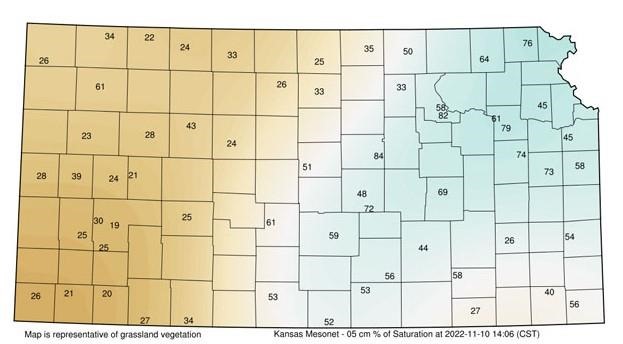

The moisture level in the topsoil will be important because dry soils will get colder easier than wet soils. Soil moisture has been generally low across most of the state during the fall, especially in western Kansas (Figure 1). Meanwhile, the central portion of the state has received varying levels of precipitation in the last week, which can help buffer negative effects of cold air temperatures.

In parts of the state where the soil has been dry enough to preclude wheat emergence, no damage should be expected. The cold temperatures will be more likely to cause injury to wheat if the plants were emerged and showing drought stress symptoms.

Figure 1. Soil moisture status (% saturation) at 5 cm (2 inch) depth for Kansas as of November 10, 2022.

Cold hardiness of the crop

Another important factor in wheat’s response to the cold is whether the wheat had time to become properly cold hardened. Although there were some heat waves in October and early November, the temperatures were overall low enough to have allowed the wheat to develop cold hardiness.

The extent of the unusually large and rapid drop in temperatures from well above normal to well below normal is a concern. If the wheat did not develop sufficient cold hardiness, it would be more susceptible to injury from the upcoming cold snap. We likely won’t know for sure until next spring as the wheat comes out of dormancy.

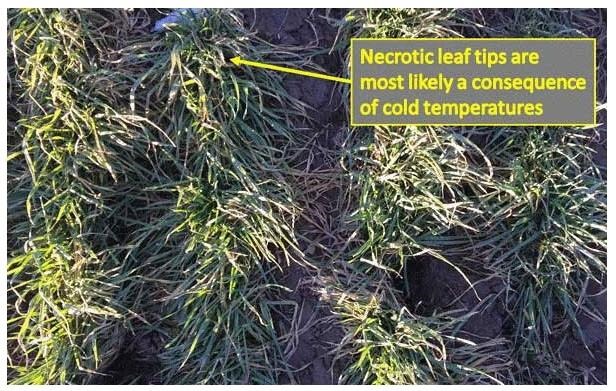

The first thing we’ll be seeing is a lot of burndown of the wheat from these cold temperatures. If the wheat was bigger than normal – which was likely not the case this year due to the dry and mild temperature conditions – the plants may look “rough” with a lot of brown dead-looking foliage on the soil surface (Figure 2). That doesn’t mean the plants are dead, however.

Figure 2. Wheat plants starting to show straw-colored or pale leaf tips as a consequence of cold temperatures near Healy. Brown, dried leaves do not necessarily indicate winter injury. The only way to assess the plant’s condition following winter is to examine the crown for winterkill.

Root system development

Two other factors to consider when assessing the likelihood of cold damage to winter wheat are fall root system development and soil temperatures at the crown level. Good top growth of wheat doesn’t necessarily indicate good root development. Poor root development is a concern where conditions have been dry. Where wheat plants have a good crown root system and two or more tillers, they will tolerate the cold better. If plants are poorly developed going into winter, with very few secondary roots and no tillers, they will be more susceptible to winterkill or desiccation, especially when soils remain dry. Poor development of secondary roots may not be readily apparent unless the plants are pulled up and examined (Figure 3). If secondary roots are poorly developed, it may be due to dry soils, poor seed-to-soil contact, very low pH, insect damage, or other causes.

Figure 3. Differences in wheat development prior to winter dormancy. Both examples shown above should be able to make it through the winter, although the more developed root system in the photo to the right will be able to provide water and nutrients with less limitations to the plant during the winter.

Soil temperatures at the crown level and crown insulation

Soil temperatures at crown level – another important determinant of wheat survival to cold temperatures – depend on snow cover, moisture levels in the soil, and seedbed conditions. Winterkill is possible if soil temperatures at the crown level (about one-inch-deep if the wheat was planted at the correct depth) fall into the single digits. If there is at least an inch of snow on the ground, the wheat will be insulated and protected, and soil temperatures will usually remain above the critical level. In addition, if the soil has good moisture, it is possible that soil temperatures at the crown level will not reach the critical level even in the absence of snow cover. However, if the soil is dry – as it is this year in a large portion of western Kansas – and there is no snow cover, there may be the potential for winterkill, especially on exposed slopes or terrace tops, depending on the condition of the plants. Dry soils and loose seedbeds warm up and cool down much faster than moist or firm soils, contributing to winter injury.

If wheat is planted at the correct depth, about 1.5 to 2 inches deep, and is in good contact with the soil, the crown should be about one inch below the soil surface and well protected from the effects of cold temperatures. If the wheat seed was planted too shallow, then the crown will have developed too close to the soil surface and will be more susceptible to winterkill. Also, if the seed was planted into loose soil or into heavy surface residue, the crown could be more exposed and susceptible to cold temperatures and desiccation.

Source : ksu.edu