By Jessalyn Bachler

How do you know when your pastures are ready to be grazed? This question is especially important in years of drought when delays in forage production are commonly seen. If you graze too early, you can harm our valuable native range plants. If you graze too late, you risk invasive plant species getting a head start and miss out on the early spring nutrition bump. Grazing timing is key when managing rangelands during a drought.

How does grazing timing affect turnout dates?

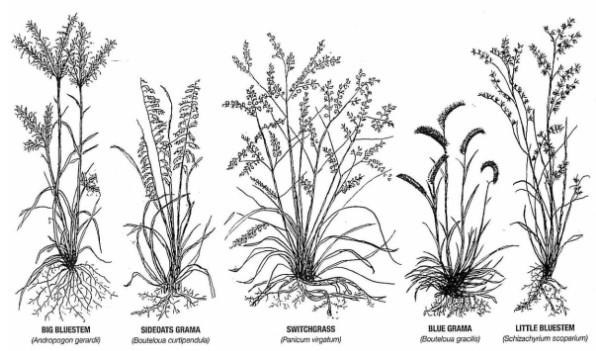

It is critical to wait to turnout livestock until pastures are ready to be grazed. This decision should be based upon grazing readiness of the plant community that is found throughout the pasture. If the pasture is dominated by native grass species, such as western wheatgrass, needlegrasses, grama grasses, and big and little bluestem (Figure 1), the pasture will likely need longer to break dormancy and get started than if it were a tame grass pasture. Native pastures should not be grazed until later in spring or early summer. On the other hand, if the pasture is invaded with tame-season grasses, such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, or crested wheatgrass, the pasture will likely be ready to be grazed in early spring. Turnout should be timed with plant species composition found in the pasture.

Across South Dakota, turnout dates can vary by region. In northwestern South Dakota, proper turnout dates for native rangeland are generally around the end of May or beginning of June; tame grass pastures are usually ready for utilization in the beginning of May. As one progresses further south in South Dakota, these dates will change, and grasses should be ready to be grazed sooner. These are general rules of thumb for when pastures might be ready for grazing. These dates can be highly impacted in a drought situation; if adequate spring moisture is not received, turnout dates will be later (see Adaptive Management: One Strategy To Increase Your Operation’s Flexibility and Resiliency). If pastures are grazed too early before the grasses are ready, seasonal forage production can be decreased, in turn causing reduced livestock performance.

Another question to ask when looking at timing of grazing is if the pasture is dominated by cool-season or warm-season grasses because the growth curve for each group of plants is different. Pastures dominated with cool-season grasses are commonly seen throughout South Dakota. Cool-season grasses tend to be highest in crude protein and total digestible nutrients early in the growing season, when they temperatures are mild. They may also get a fall regrowth when temperatures cool down. Warm-season grasses are in active growth and have higher nutritional contents during the hot months of summer. Thus, timing of grazing is important to not only maximize forage production, but also to allow grazing to occur on the highest quality forage at the proper time to meet livestock nutrient requirements. Being able to identify the plant communities that are present in pastures will help ranchers utilize their available forage base to its fullest potential.

Figure 1. Native grasses that are commonly found throughout South Dakota rangelands.

When is the range ready to be grazed?

Figure 2. Crested wheatgrass ready to be grazed at the three-leaf stage.

After plant communities are identified in pastures, it is time to look at grazing readiness. One way to measure grazing readiness is to look at growing degree days (see Options for Spring Turnout). Another way to assess grazing readiness is to look at actual forage growth of the plant community in your pasture to see what stage the grasses are at.

Native cool-season grasses, such as western wheatgrass and green needlegrass, should not be grazed until they reach the 3.5-leaf stage to ensure no harm will be done to the plant. If native grasses are grazed too early, not only will it reduce forage production, but it will also cause negative changes in the plant community, such as allowing invasive grasses or weeds to become established. Pastures that are dominated with cool-season tame grasses, such as Kentucky bluegrass, crested wheatgrass and smooth brome are ready for grazing at the three-leaf stage (Figure 2). Tame grasses tend to reach maturity earlier and handle grazing pressure better; therefore, it is recommended to utilize these pastures first for spring grazing.

How does drought affect the timing of grazing?

Spring moisture and temperatures play the largest role in determining spring forage growth. This is particularly true of the months of April, May and June. Research has demonstrated that precipitation received during these months accurately predicts annual forage production in the central and northern Great Plains (Smart et al. 2020). Typically, if there is a drought and timely spring rains are received in April and May, we can possibly see normal amounts of forage production if soil moisture reserves were refilled the previous fall. If there is not sufficient spring moisture and turnout needs to be delayed, producers should expect to feed livestock longer until forage production is adequate for turnout.

As critical as spring moisture is, it is crucial to not downplay the importance of previous grazing management, as it will largely influence forage production as well. If pastures were harshly overgrazed in years prior, they need adequate time (up to a year) to recover. However, if pastures were managed with proper grazing management and enough residual plant material was left behind after grazing, a pasture may only need a few months to recover. It all comes down to how well you manage your grazing before a drought hits!

Summary

The type of plants that are found throughout your pastures will indicate when they are ready to be grazed. As a rule of thumb, tame grasses should always be grazed before native grasses in the spring. Pastures that are dominated by cool-season grasses should be utilized in spring and fall, while warm-season pastures should be grazed in the heat of summer. The timing of spring turnout dates for grazing can vary from year to year, depending upon spring moisture (drought status) and previous management. Thus, it is critical for ranchers to “read the range” to identify when their pastures are ready to be grazed, especially in years of drought.

Source : sdstate.edu