If dairying were as easy as milking a cow and collecting income on the milk, everyone would be doing it. Right? The reality is that dairy farmers have an extensive list of tasks – among them are efforts to protect animal health and welfare. Producers may have a refrigerator full of vaccines and medicines to deal with a host of diseases that can affect the health, welfare, and productivity of their cows. But what if they are treating one ailment because a different, undetected virus is impairing the animal’s immune system?

You will not find a vaccine or medicine labeled to treat Bovine Leukemia Virus (BLV), but in some cases, it is the hidden culprit

If the farm doesn’t test for BLV, the virus and any resulting illness or death will remain hidden as unassigned health problems. We’ve consistently heard from producers about how some animals do great on the farm – until they don’t. These animals produce milk and may have repeated treatments for poor health, but nothing that stands out in management systems. Then one day, the animal stops – stops lactating, maintaining health, or even living. These animals are found to be BLV-positive animals, finally succumbing to the effects of the virus. Let’s dive further into this virus and how it can be managed.

Enzootic Bovine Leukosis is a contagious disease in cattle caused by BLV

Today, 21 countries have eradicated the disease by testing and removing animals that showed an immune response to the virus. The U.S. and Canada ignored eradication measures in the 1970’s when overall infection rates were below 10%. Today, most U.S. dairy farms have BLV with upwards of 50% of cattle on each farm testing positive for BLV. There is currently no cure or vaccine available, and infected cattle will carry the virus for life. While animals infected with BLV may not show any indications of carrying the disease, other profit-related issues may arise.

Cows infected with BLV suffer from the following consequences:

Decreased milk production. We see that first lactation milking heifers typically produce the same amount of milk regardless of infection. However, as the BLV- infected cow ages, she exhibits lower milk production than her non-infected herd mates. In general, a higher BLV herd prevalence is associated with a lower rolling herd average, and infected cows have a lower predicted 305-day mature equivalent milk yield. Also, genetically superior animals infected with BLV under-perform their estimated genetic potential.

Decreased lifetime within the herd. BLV-infected cows are likely to be removed from the herd earlier than their uninfected herd mates (i.e., have a lower herd longevity). As such, BLV-infected cows often have a lower economic return due to a shortened productive life. Moreover, consumer perception of animal welfare issues may be raised around BLV prevalence on U.S. dairy farms.

Decrease reproductive success. Cows infected with BLV need to be bred more times to obtain a pregnancy and have longer calving intervals. In rare cases, BLV-infected cows may develop tumors in the uterus resulting in the inability to become pregnant.

Risk of slaughter condemnation. Tumor development may occur in animals with high levels of virus. These tumors are the main reason for carcass condemnation at slaughter by USDA inspectors.

Negative economic impacts. It is challenging to estimate the true economic impact of BLV, given the multitude of underlying and confounding factors. In 2017, our team estimated an annual loss of approximately $283 per milking cow, resulting in a $2.7 billion national deficit due to BLV.

Bovine Leukemia Virus: A Hidden but Damaging Infection

BLV is a virus that integrates into cattle DNA. The virus favors integration into a type of lymphocyte, the B-cell. These immune cells are best known for their ability to produce antibodies against pathogens. By integrating - or hiding - within the cattle’s own cells, BLV can remain undetected by the animal’s immune system leading to a persistent, life-long infection.

Within a few weeks after initial infection, the animal typically maintains a normal number of lymphocytes but antibodies to the virus can already be detected. Antibodies to BLV indicate that the animal’s immune system has identified BLV as a stowaway and has started to create mechanisms to recognize and potentially fight the hidden invader. At this point, however, the virus remains hidden, or latent, without doing much damage. Most cattle infected with BLV can be found in this stage of bovine leukosis and lack any sign of illness. These cattle simply act as carriers of the virus.

After a period of hiding, ranging from months to years, BLV begins replicate. Approximately one-third of cattle infected with BLV will exhibit an increased number of blood lymphocytes due to abnormal replication of BLV- infected cells. This phase of BLV replication leads to a decrease in immune system function – allowing other pathogens or infections to develop. An ongoing study has collected samples from groups of cattle across multiple Michigan dairy farms, and we have found that animals with BLV suffer an impaired response to vaccines. These cattle may become ill due to a wide variety of ailments or suffer health issues, such as lameness and mastitis, due to immune system dysregulation caused by BLV.

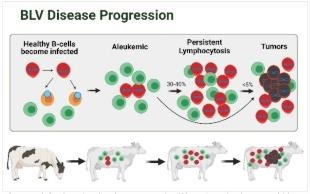

After BLV infection, the virus incorporates itself into the animals’ DNA within lymphocyte cells. There the virus can remain silent or “latent” within the cell, undetected by the animal’s immune system. However, 30% - 40% of BLV-infected animals will experience lymphocyte cell growth due to BLV influencing cell replication. Cell growth may cause a depressed immune system within the animal. Only a few (<5%) of the animals infected with BLV will display tumor growth due to a mutation in the infected cells, causing them to replicate and form a solid mass. Cattle with a tumor due to bovine leukosis will suffer early death and condemnation at slaughter. Image modified from EFSA Panel Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW): Enzootic bovine leukosis (2015).

Less than 5% of BLV-infected cattle will develop dramatically elevated lymphocyte numbers, tumors (lymphosarcoma), and death due to BLV infections. Animals suffering terminal stages of bovine leukosis are characterized by loss of body condition and overall weakness preceding death. Tumors associated with BLV infection are one of the leading causes of carcass condemnations in U.S. dairy cattle. Regardless of stage of disease, animal welfare continues to be of concern, as do associated effects on cattle health and productivity.

The disease progresses differently in each animal. Sometimes the disease generates tumors and leads to death, while other cattle simply harbor the virus, showing no direct signs of illness – all the while spreading the virus to their herd mates.

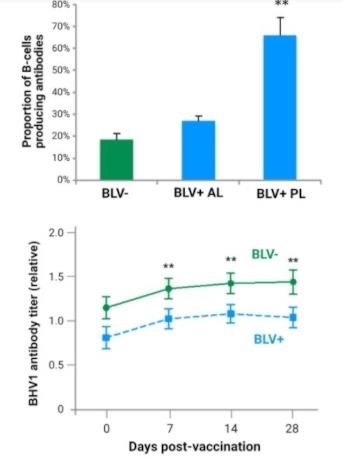

B-cells are part of the immune system, producing antibodies against pathogens, such as BLV. The top graph shows antibody producing B-cells in animals uninfected, or BLV negative (green bar) and BLV-infected (blue bars) cows. The two blue bars indicate BLV-infected cows at two different stages of bovine leukosis: aleukemic (BLV+ AL) and persistent lymphocytotic (BLV+ PL) cows. Aleukemic (BLV+ AL) cows have lymphocyte counts near healthy (BLV-) cows while persistent lymphocytoitic (BLV+ PL) cows have elevated lymphocyte numbers. Vaccines and boosters provide the animal with the ability to create antibodies to fight against the pathogen. The bottom graph shows 28-day bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV1) antibody titer levels between BLV-infected and uninfected cows. Cows were given a normal booster dose of a commercial multi-valent vaccine on day 0. The level of antibodies against BHV1 were monitored each week for three weeks. Antibodies against BHV1 were lower in BLV-infected cows. Two other antibody levels were tested (Leptospira hardjo and Leptospira Pomona) and showed similar results. These results demonstrate a decrease in vaccine efficiency within BLV-infected cattle. Lower panel modified from Frie et al., Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol., 2016.

Tools and Management Strategies to Reduce BLV

Michigan State University scientists and their collaborators continue to work with producers across the country to study bovine leukosis, viral progression, and management strategies for a healthier, more productive herd.

Our team has established management tools and protocols to identify the most infectious cattle for removal, even when removal of all infected animals is not economically viable. Once BLV prevalence falls to a low level, the farm may then opt to remove all infected cattle to “Move to Zero” and become a BLV-free herd. Management strategies should also include prevention of new infections through proper calf care, testing of purchased replacements, and potentially segregation of infected animals.

Preventing Transmission

The most recognized route of BLV infection is transmission of infected lymphocytes (via blood) from one animal to another. While the tiniest drop of blood can be sufficient to cause infection, it’s more likely that repeated blood-to-blood exposures ultimately lead to BLV transmission between animals. Small amounts of blood can be transferred when using the same equipment between animals for injections, rectal palpations, foot trims, ear tagging, tattooing, dehorning, and other procedures. Single-use needles and reproductive exam sleeves are often recommended, and the use of fly control has also been shown to reduce BLV infections.

Calves can become infected by consuming BLV- infected colostrum. Freezing or pasteurizing colostrum will kill the virus, preventing BLV replication. Therefore, using processed colostrum or milk replacer will reduce the risk of transmission. Colostrum collected from BLV-infected dams contains maternal BLV antibodies, and studies have indicated that calves fed colostrum with maternal BLV antibodies may be protected from advanced stages of bovine leukosis. Research to investigate the best calf feeding regimen for animal longevity and health is an important ongoing effort.

Bovine leukemia virus has been found in nasal secretions and saliva, but at a much lower concentration than that found in the blood of an infected animal. A low risk of BLV transmission may occur with nose-to-nose contact, natural mating, or dam-to-fetus transfer in utero.

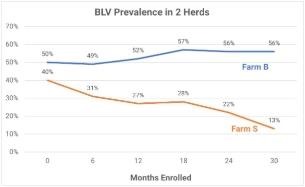

Farm B uses needles only once but reuses palpation sleeves, struggles with fly control, and was not able to prioritize BLV control in the face of other management challenges. Super shedders (the most infectious cows) in the herd were not culled. Farm S uses needles and palpation sleeves once, pasteurizes colostrum and calf milk, prioritizes fly control, uses BLV status in herd management software to make breeding and culling decisions, and has aggressively culled super shedders. These examples show the impact of recommended practices on BLV infection rates in just 2.5 years of effort.

Management Strategies

Our research team, in collaboration with CentralStar Cooperative, has developed a multi-step approach to reduce herd BLV prevalence. The first step determines the herd’s overall BLV prevalence by testing for BLV antibodies (by ELISA). Typically, this testing is performed on the milking herd through DHI, with owner-submitted milk samples, or in serum from submitted blood samples. In most cases, the BLV ELISA prevalence is high enough that culling all BLV- antibody-positive cattle would be economically inviable. The second step of the screening process includes collecting a whole blood sample from BLV-antibody- positive cattle and measuring the concentration of BLV (proviral load). This identifies the “super shedders,” or the most infectious cows that should be separated and removed from the herd as soon as possible. Success of these programs relies on how aggressive the farm can afford to be in removing BLV-positive animals, while preventing incoming infections from replacements.

Genetic Selection

Like humans and other animals, the immune system of cattle can respond to a wide range of pathogens. The genes important for proper immune function are directly inherited from the sire and dam. Not surprisingly, genetics play a role in an animal’s response to BLV infection. One important and diverse DNA region is known as the bovine leukocyte antigen (BoLA) gene.

Research suggests that some versions of the gene are associated with BLV resistance, defined as maintaining a low amount of virus even after prolonged BLV infection. Conversely, other versions of this gene may increase susceptibility to BLV infection. One avenue of research is examining a potential link between BoLA and the possibility of the removal of infected cells by other parts of the immune system. As research to determine genetic associations related to BLV resistance advances, selection of breeding stock to aid in lowering BLV prevalence within a herd may be possible.

The Future of BLV Research at MSU

The MSU BLV research team continues to collaborate with external researchers to enhance our understanding of the biological and economic impacts of BLV. We hold an annual “All Things BLV Meeting” for the researchers and interested producers, and we host an interactive website that serves as a portal for BLV information. We strive to collaborate with and learn from producers, providing tools and management strategies for improved profitability and healthier animals. A subset of collaborating farms have followed our proposed management programs and are nearing a BLV-free herd status. Over the next year, we hope to provide a low-cost monitoring test for BLV-free herds to validate and maintain their BLV-free status. Additionally, we hope to organize new recognition platforms for BLV- free farms to allow them to showcase their hard work.

Our laboratories and research projects also provide opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students to receive mentoring, carry out research, and gain experience within the dairy industry. Over the next few years, we hope our work can answer some of the following questions:

When does BLV transmission commonly happen and how is the animal’s lifespan affected?

We have found that dairy cows typically exhibit an increase in lymphocyte cells due to BLV replication at the start of their second lactation. However, we believe cows are becoming exposed and infected with the virus well before the second lactation. We started a 5-year USDA-funded project in Spring 2021 and are sampling calves at birth, before breeding, 60 days pregnant, and at entry into the milking herd to determine when the animal first becomes exposed to the virus. By tracking the animal over 3-4 lactations, we will also be able to determine if the time of infection affects the animal’s longevity within the herd.

What’s to be gained from reducing BLV herd prevalence?

A study on Michigan dairy herds indicated that BLV- positive cows are 23% more likely to die or be culled than their BLV-negative herd mates over a 19-month period. Additionally, cattle with BLV are known to succumb to other diseases or infections which require treatment. Treatments or unexpected deaths provide an economic strain on the farmer. Beginning this fall, we will be incorporating producer financial data (TelFarm) and animal data from commercial farms for an updated, inclusive economic assessment of BLV. Our project will create interactive producer tools and economic assessments focused on the impact of BLV and the economic effectiveness of BLV management programs.

What are the triggers that cause BLV to come out of hiding and begin replicating in an animal?

The ability of BLV to make copies of itself is largely controlled by many of the same proteins that control the normal growth of B-cells responding to a vaccine. We have evidence that stimulation of the immune system (e.g., vaccination) may cause BLV to begin replicating and increase proviral load. Although temporary, this increase may make such animals more infectious for a period of time. If these observations are validated, the results might lead to management strategies to control BLV transmission following periods of vaccine administration.

What about BLV in beef herds?

Bovine leukemia virus also infects beef cattle, but much less is known about its impact. Survey projects have found that BLV-infected beef cattle are at an 18% greater culling risk than uninfected herd mates. Within Michigan, 26% of breeding beef bulls between 1-10 years old were infected with BLV. In 2017, 34% of the beef cattle in the U.S. slaughterhouses tested positive for BLV, a 20% increase in 20 years.

While transmission of BLV via semen is usually considered unlikely, there are major international trade restrictions on semen from BLV-infected bulls. Collaborative projects have been initiated to explore BLV prevalence and disease progression in U.S. beef cattle and genetic factors contributing to advanced stages of BLV-induced disease. Working with beef producers, we can adapt management strategies that produced positive outcomes in dairy herds.

The MSU BLV research team includes experts with wide-ranging expertise in genetics, epidemiology, veterinary medicine, economics, and outreach, all of whom are proud to work with dairy and beef farmers. We pride ourselves on listening during producer conversations, to enable us to conduct practical research that will promote the success of the farm and health of the animals. We are grateful for the producers who have collaborated with our research team and look forward to continued growth in these collaborations.

Consumers continue to focus on individual animal health and welfare issues linked to products they purchase. The industry needs to act proactively to be ready to address consumer concerns. Starting the discussion of herd BLV prevalence, utilizing our economic estimation tool to understand the benefits of BLV management, and learning from other producers’ experiences provide the foundation to addressing BLV. We encourage anyone to reach out to a BLV team member to share ideas, seek advice, or look for more information.

Source : msu.edu