By Jonathan Coppess, Nick Paulson et.al

Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics

University of Illinois

By Carl Zulauf

Department of Agricultural, Environmental and Development Economics

Ohio State University

On Friday, March 27, 2020, Congress passed, and President Trump signed into law, the 3rd FY2020 Coronavirus Supplemental Appropriations Act (P.L. 116-136). At a reported appropriation of $2 trillion, the bill is the largest federal economic relief measure ever enacted (Snell, March 26, 2020; Siegel-Bernard and Lieber, March 28, 2020; Cochrane, March 30, 2020). This article reviews the funding for USDA agencies and programs in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, including reimbursement of Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) expenditures, rural assistance and food assistance.

Background

On December 31, 2019, China first confirmed an outbreak of the novel coronavirus with its first reported death on January 11, 2020; the first confirmed case in the U.S. was in Washington State around January 20-21, 2020, by a man in his thirties who had traveled from Wuhan, China on January 15, 2020 (Taylor, March 27, 2020; Rabin, January 21, 2020). On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (W.H.O.) declared a global health emergency and on February 11, the W.H.O. officially named the disease caused by the novel coronavirus as COVID-19. The first reported death in the United States was in Seattle on February 28, the same date that infections in Europe were reported to have spiked. As of April 1, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 186,101 cases in the United States (CDC Coronavirus Disease 2019). As many as 941,000 people are reported to have been infected with the novel coronavirus worldwide (CNN).

The $2 trillion relief package began with a bill negotiated among Senate Republicans released on March 19, 2020, followed by five days of negotiations and approval by the Senate by a margin of 96 to 0 just before midnight on Wednesday, March 25, 2020 (Cochrane, Tankersley and Rappeport, March 19, 2020; Cochrane and Fandos, March 25, 2020). The House of Representatives passed the measure by voice vote on March 27, 2020, after avoiding an attempt to use procedural maneuvers to block action; President Trump signed it that evening (Cochrane and Stolberg, March 27, 2020). Barely more than a week from introduction to signing of the bill represents an extraordinarily rapid turnaround by Congress of legislation to respond to this public health emergency; more stunning still given the sheer size of expected spending and the scope of the reach of the bill’s provisions.

Discussion: USDA Funding in the CARES Act

The coronavirus relief bill titled Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security or CARES Act contains two Divisions (H.R. 748). The Division A addresses assistance to employees and businesses, as well as assistance to the health care system and providers. It also includes economic stabilization provisions for severely distressed sectors of the U.S. economy. Division B of the bill includes emergency supplemental appropriations provisions for various accounts or to agencies for use in response. The funding for the U.S. Department of Agriculture accounts are in this Division, with the bill providing a total of $48.4 billion. These funds can be divided into two basic categories: (1) operational funding for salaries and other expenses to cover costs for response efforts or usual operating efforts that have required additional costs; and (2) direct relief funding or reimbursement for funds previously spent in direct assistance. The following discussion reviews the funding in these two categories.

(1) Funding for USDA Operational Needs

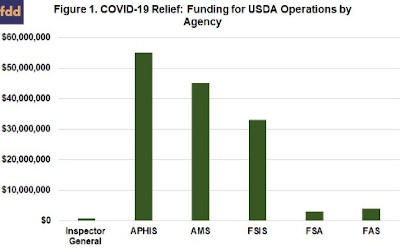

In general, the bill provides $140.75 million to USDA agencies for helping with salaries and expenses in light of the coronavirus pandemic. For example, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is appropriated an additional $55 million to “prevent, prepare for, and respond to” the pandemic, including costs for the Agriculture Quarantine and Inspection Program. The Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) is also appropriated additional amounts ($45 million) for prevention, preparation and response, including additional costs for grading, inspecting and audit activities for commodities. The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) received an additional $33 million for its efforts, including supporting temporary workers or relocating inspectors, as well as overtime for inspectors under the Federal Meat Inspection Act, the Poultry Products Inspection Act, and the Egg Products Inspection Act. Figure 1 illustrates the emergency funding appropriated to the various USDA agency accounts.

Note that the Farm Service Agency (FSA) received additional funds ($3 million) to cover additional expenses, including for temporary staff and overtime, while the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) received additional funds ($4 million) that included expenses for relocating employees and dependents from overseas posts. Finally, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) received $750,000 for audits and investigations of the activities carried out and expenditures under this emergency act.

(2) Funding for Direct Assistance

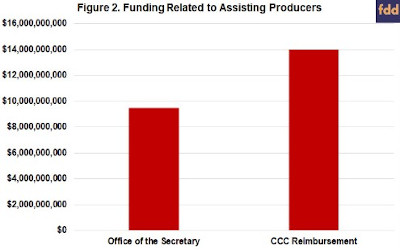

In total, this is the largest portion of the funding provided in the CARES Act to USDA at just over $48.3 billion. Funds are largely for three different program activities. The first, illustrated in Figure 2, are the funds for providing direct assistance to producers. The $23.5 billion includes $9.5 billion to the Secretary of Agriculture to support producers impacted by coronavirus but it specifically mentions “producers of specialty crops, producers that supply local food systems, including farmers markets, restaurants, and schools” as well as “livestock producers, including dairy producers” (Division B, Title I). The way it is written, it appears unlikely that any of these funds are to be used to support producers of the commodities generally covered in Title I of a farm bill (except dairy).

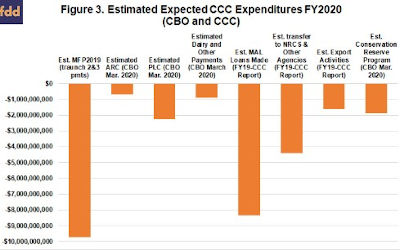

The second account funded is a $14 billion reimbursement of the net realized losses of the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) not previously reimbursed. This is not a direct appropriation for new spending or the creation of new programs and payments but rather a reimbursement for funds already spent by the CCC. In general, the CCC Charter Act of 1948 provides authority to USDA to spend funds on a line of credit from the federal treasury; the cap on that line of credit is $30 billion (USDA, CCC Charter Act). The CCC line of credit is used to make farm program payments, conservation payments (including transfers to NRCS and other agencies), Marketing Assistance Loans and export activities pursuant to programs authorized in the farm bill. The CCC Charter Act also provides specific authorities for assisting commodities, markets for commodities (domestic and export) and similar efforts. Notably, it is the specific authorities in section 5 of the Charter Act that were used by USDA to create the Market Facilitation Program (MFP) and provided related trade assistance in 2018 and 2019. An initial estimate of CCC spending to date compiled from Congressional Budget Office forecasts and the fiscal year 2019 CCC report offers a perspective although not an actual accounting for the line of credit. It is illustrated in Figure 3.

Based on this estimate, CCC would be expected to spend $29.6 billion of the $30 billion line of credit in FY2020 to cover programs, payments and other obligations already in the budget. The reimbursement in the CARES Act most likely reimburses spending for the second and third tranches of the 2019 MFP payments (estimated $9.7 billion), the estimated ARC/PLC payments for the 2018 crop made in October 2019 (estimated $2.9 billion) and possibly CRP rental payments (estimated $1.9 billion). Whether this reimbursement allows for USDA to initiate a new round of commodity program payments to farmers program remains an open question.

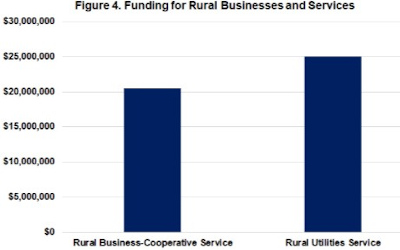

The CARES Act also appropriated additional funding to Rural Development agencies. The Rural Business Program operated by the Rural Business-Cooperative Service received an additional $20.5 million for loans to rural businesses. The Rural Utilities Service received an additional $25 million for “telemedicine and distance learning services in rural areas”; especially helpful assistance as schools are transitioning to online learning and hospitals in rural areas brace for the need to respond to the pandemic. Figure 4 illustrates the additional funding for these accounts.

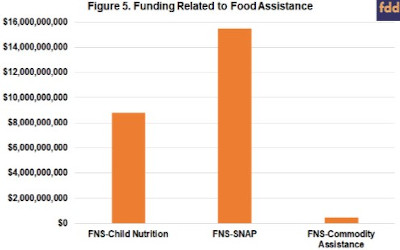

The CARES Act also provides approximately $24.8 billion in additional emergency funds for food assistance. Child Nutrition Programs received $8.8 billion in additional emergency funds to help with needs due to the pandemic, and the Commodity Assistance Program received $450 million, with $150 million used for costs associated with the distribution of commodities. Figure 5 illustrates the emergency funding related to food assistance accounts listed in the CARES Act.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is also illustrated in Figure 5 with $15.8 billion in additional funds. Notably, $15.5 billion of that is to be held in a contingency reserve for use if cost or participation exceeds budget estimates. Also, $100 million is for food distribution on Indian reservations, with $50 million for facility improvements and upgrades, $50 million for food purchases and $200 million for grants to the Commonwealth of the Northern Marian Islands, Puerto Rico and American Samoa for nutrition assistance.

It is the provision for SNAP that draws particular attention. Recall that SNAP provides direct assistance to individuals and families for the purchase of food with eligibility generally to those who are below 130% of the poverty line. This is a category of Americans likely to grow substantially in coming months given the extraordinary shock to the economy from the efforts to slow the spread of the coronavirus and flatten the curve (Roberts, March 27, 2020). For example, the U.S. Labor Department reported that an all-time record 3.3 million Americans applied for unemployment benefits from March 15 to March 21 (Long and Flowers, March 26, 2020). The Labor Department reported an additional 6.6 million people filed new claims for unemployment this past week (Casselman and Cohen, April 2, 2020). By comparison, the highest number of unemployment claims during the Great Recession was 665,000 in March 2009 and the previous high was 695,000 in 1982.

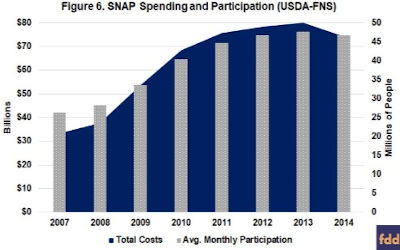

SNAP assistance to purchase food is counter-cyclical and is expected to increase spending and participation as more and more people fall below the poverty thresholds for the program. For a point of reference, SNAP spending increased drastically in the wake of the Great Recession that followed the economic collapse in the fall of 2008. Figure 6 illustrates SNAP during the Great Recession. The navy area represents the total costs as reported by USDA-FNS and the gray bars are the total average monthly participation, millions of people receiving benefits (SNAP Data Tables). Total costs of the SNAP program increased from $37.6 billion in 2008 to $53.6 billion in 2009, peaking at $79.9 billion in 2013.

Note that some of the SNAP spending illustrated in Figure 6 was the result of temporary policy changes contained in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. ARRA increased benefits and expanded eligibility in the wake of the economic collapse by an estimated $20.74 billion (Brass et al., CRS 2009). Specifically, ARRA increased the maximum monthly benefits a person or household could receive by 13.6% by replacing the annual food cost inflation indexing with an across-the-board increase beginning April, 2009; the effective result for the average household was a 15% increase in SNAP benefits (Aussenberg, Monke and Falk, CRS 2010). Because it was a temporary replacement for annual inflation, the increase was expected to end in FY2018 as inflation caught up; Congress revised the program again in 2010, scheduling the increase to end earlier. While the CARES Act does include additional emergency assistance for SNAP (Figure 5), it is a fixed contingency amount and not the broadly applicable benefit increase as was included in ARRA.

Concluding Thoughts

On this matter an overused word is applicable; the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act is an unprecedented response, both in terms of total spending ($2 trillion) and the quick turnaround by Congress, to a global pandemic and public health crisis unlike anything since the global flu pandemic in 1918. The CARES Act is also the third phase in a series of increasingly larger legislative responses as the pandemic unfolded, but unlikely to be the last. If the current social distancing measures continue for an extended period of time, the impacts on families and businesses could be unfathomable; CARES may be just a down payment.

Reviewing the provisions to USDA agencies and programs indicates some relief targeted to specialty crop and livestock farmers, as well as rural businesses, schools and healthcare. It leaves as an open question what is available for USDA to use in providing additional assistance to farmers that typically receive farm program payments. The CARES Act leaves other open questions as well. Central among them are questions involving SNAP, especially as compared to experiences in the Great Recession and with the 2009 recovery act.

Next to healthcare needs, it is difficult to imagine anything more important to individuals and families in this crisis than being able to put food on the table. It has been reported, however, that negotiations stumbled over partisan opposition to increasing SNAP benefits and that an increase of the CCC cap to $50 billion was dropped as a result (Carney and Lillis, March 24, 2020; Ferguson and Krawzak, March 23, 2020; Boudreau and McCrimmon, March 23, 2020). If the reports are accurate, this development should be deeply concerning both from general public policy and farm bill/farm policy perspectives. Partisan opposition to SNAP fueled problems in the 2014 and 2018 farm bill debates, a feud over this vital program and critical coalition in efforts to respond to this crisis would seem to represent a major, troubling escalation.

Much remains unknown, uncertain and unsettling in the wake of this pandemic. It is therefore of paramount importance that cooler, more conscientious heads prevail at this perilous moment; critical in a society that needs to pull together even as we individually embark on extraordinary efforts at social distancing. At the core should be sincere efforts toward ensuring that every person receives the assistance they need in these most difficult times.

Source : illinois.edu