By Aaron Saeugling

The 2021 cropping year will be remembered for a long time as an unusual year in many respects. Corn and soybean growth are off like a turtle race in many locations this season. So, we may be driving around, doing some road scouting, and asking ourselves why this is taking so long. After all, the markets are going up and we would feel better if we could evaluate our stands.

While conditions were dry in most locations and we planted early, we also have had unusually cool conditions. Several things to consider as we worry about the crop:

- Did you plant deeper than normal?

- Did you do less tillage?

- Did you make changes to your planter?

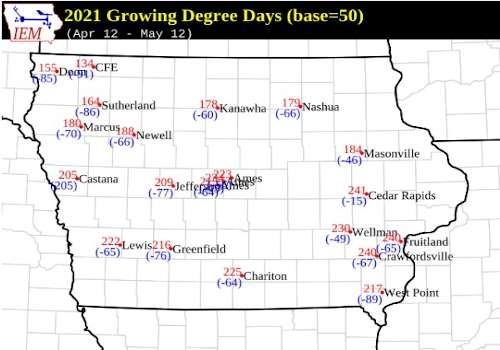

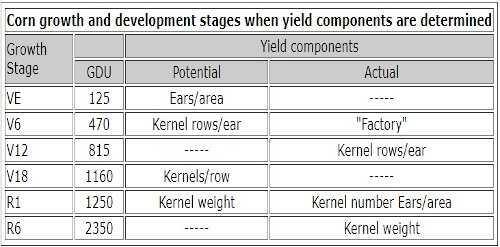

If you answered ‘yes’ to any of these questions, emergence may just take some more time than we’re used to. Keep in mind that once the seed goes in the ground, we are at the mercy of Mother Nature and accumulation of growing degree days/units (GDDs/GDUs) for crop growth and development. Below are a couple of charts to reference when we are out scouting to understand the implication of a cool start to the season. For more farm specific information, use the following website to help predict crop development this season: https://hprcc.unl.edu/agroclimate/gdd.php.

Figure 1. Accumulated growing degree days (base 50 F) in Iowa from April 12 – May 12, 2021.

Figure 2. Corn growth and development stages when yield components are determined.

Source : iastate.edu