A computer software package widely used in the Midwest to strategically position riparian buffers and other structures aimed at protecting water quality on agricultural land can be used effectively in the eastern United States, with some limitations, Penn State researchers report in a new study.

The Agriculture Conservation Planning Framework (ACPF) applies high-resolution soil maps and topographic data, now available for many areas of the U.S., to show locations for the placement of conservation devices that provide the greatest benefits in agricultural watersheds. The geospatial tool was developed in Iowa and also has been used successfully in Nebraska, Wisconsin and Ohio.

However, most most of the water-quality protection devices can be used in the Chesapeake Bay drainage and in other Northeastern watersheds, according to the study’s lead author Jonathan Duncan, assistant professor of hydrology, College of Agricultural Sciences. Calling the framework “high-precision conservation,” he suggested that its application to watersheds in the eastern United States represents both opportunity and challenge for conservation planning.

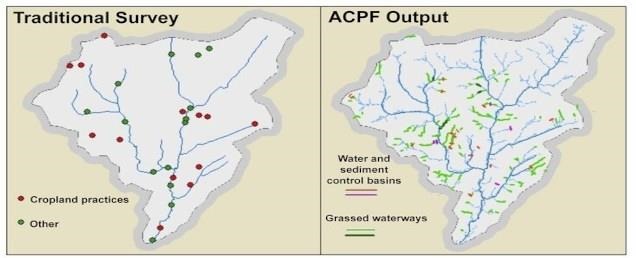

This graphic from the study contrasts watershed-planning maps from traditional, expert-based assessment (left) and Agricultural Conservation Planning Framework (ACPF) assessment of row-crop-in-field practices of water and sediment control basins and grassed waterways for a small watershed within the Susquehanna River Basin. IMAGE: PENN STATE

“In the Chesapeake Bay watershed, we have seen that best-management practices don’t always work, and one reason might be because they’re going into the wrong parts of the landscape,” Duncan said. “This ACPF tool helps address this problem, and it can identify potential locations for the positioning of the right practice in the right place to improve Chesapeake Bay water quality.”

However, he emphasized, ACPF must be adjusted for ways in which Pennsylvania’s landscape differs from the Midwest.

The Agriculture Conservation Planning Framework is used as a tool in agricultural watershed management by identifying site-specific opportunities to install conservation practices across small watersheds. The approach provides a menu of conservation options such as riparian buffers, grass waterways, filter strips, wetlands and impoundments on farms.

The framework is used in conjunction with local knowledge of water and soil resources, landscape features, and producer conservation preferences to provide a better understanding of the options available in developing watershed conservation plans, Duncan pointed out. The ACPF concept focuses on soil conservation as the foundation to agricultural watershed management.

The Agriculture Conservation Planning Framework provides a menu of conservation options such as riparian buffers (shown here), grass waterways, filter strips, wetlands and impoundments on farms. IMAGE: GETTYIMAGES 4 LOOPS

To determine whether ACPF would work in the Northeast, the researchers analyzed the application of the tool in eight watersheds in the eastern United States, from Vermont to North Carolina. They assessed ACPF’s strengths and weaknesses and analyzed the opportunities and threats resulting from employing the tool in the East.

In findings published today (Sept. 14) in Agricultural & Environmental Letters, the researchers reported that there are many potential locations where ACPF can be used in the East, but its applicability is not universal. Understanding its limitations is necessary to avoid the potential for inappropriate application and ensure appropriate adaptation, they cautioned.

Among potential limitations to successful application of ACPF outside of its original context is that some of its conservation practices are impractical in Eastern agricultural settings. For example, the researchers noted, Eastern field sizes are so small that water- and sediment-control basins and nutrient-removal wetlands are often too intrusive to be recommended.

“We see a future for ACPF in the Northeast, and in the Chesapeake Bay watershed in particular,” said Duncan. “But the adoption and utility of the tool requires interaction with scientists and conservation planners familiar with the region to avoid misapplication. Candid communications with stakeholders and local partners will help set realistic expectations about the tool.”

One of the limitations of using ACPF in the Chesapeake Bay drainage is that some of its conservation practices are impractical in Eastern agricultural settings. For example, the researchers noted, Eastern field sizes are so small that water- and sediment-control basins (such as the one shown) and nutrient-removal wetlands are often too intrusive to be recommended. IMAGE: LYNDA RICHARDSON, USDA NRCS

The ACPF framework identifies locations where specific landscape attributes are favorable for implementing certain conservation practices and includes methods to help prioritize these locations according to their susceptibility to runoff and erosion, Duncan explained. He added that a large part of the agricultural pollution problem in the Northeast is coming from a very small part of the landscape.

“If ACPF can identify the best locations for installing conservation structures, that’s better than what we’ve done to date,” he said. “It’s not like pixie dust — you can’t just sprinkle best management practices across the landscape and have them magically work well. We know they must be placed in the right locations. But at the same time, we don’t know every location in every watershed — so that’s where this tool can be super helpful.”

Also involved in this research at Penn State were Matthew Royer, director of the Agriculture and Environment Center in the College of Agricultural Sciences, and William Ryan, a master’s degree student in soil science. Other members of the research team were Zachary Respess, extension associate with North Carolina State University, formerly a master’s degree student in Duncan’s research group at Penn State; Rob Austin and Deanna Osmond, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, North Carolina State University; and Peter Kleinman, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service funded the research through its Conservation Effects Assessment Program.

Researcher Zach Respess surveying a riparian zone and stream in central Pennsylvania. IMAGE: JONATHAN DUNCAN/PENN STATE

Source : psu.edu