By Justin McMechan, Thomas Hunt and Robert Wright

In late June of 2018, entomologists in Iowa, Nebraska, and South Dakota began receiving reports of soybean fields with visible signs of dead or dying plants that were found to be associated with soybean gall midge infestations. Field surveys were initiated in these states and in neighboring Minnesota to determine the distribution and the extent of the damage.

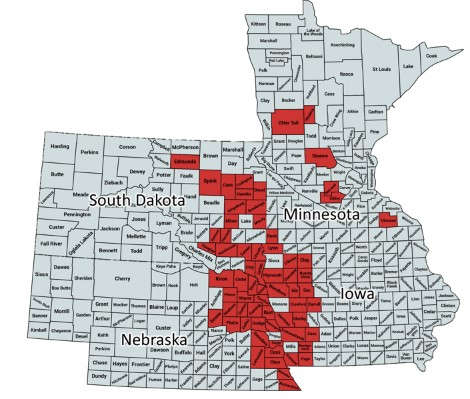

Figure 1. Counties colored in red indicate the presence of soybean gall midge.

Results found that soybean gall midge was present in 66 counties across the four states (Figure 1). This multistate map was the result of a collaboration with Erin Hodgson, Iowa State University Extension entomologist; Adam Varenhorst, South Dakota State University Extension field crops entomologist; Bruce Potter, University of Minnesota integrated pest management specialist; and UNL entomologists.

Figure 2. The distribution of damaged or dead soybean plants from the field edge.

A portion of the fields surveyed had significant levels of damage with a high frequency of dead plants at the field edge with decreasing damage from the edge into the center of the field (Figure 2). Live soybean plants in damaged areas of the field had dark discolorations at the soil surface that extended up to the unifoliate node (Figure 3a). These plants easily snapped off at the soil surface revealing white to orange larvae that appeared to be feeding on the darkened areas of the plant (Figure 3b,c). Additionally, infested plants were observed to have swollen stems near the soil surface or in close proximity to the feeding larvae.

Soybean Gall Midge Adults Identified

Adults of soybean gall midge had not been observed. In Nebraska, emergence cages were placed over midge-infested soybean plants on August 1 and adults later identified to the genus Resseliella were collected within 24 hours from these cages. Emergence of these adults continued for the next 18 days with the last observation on August 19. These specimens were sent to Raymond Gagne, collaborator in the USDA ARS Systematic Entomology Laboratory, and Junichi Yukawa, emeritus professor of Kyushu University, Japan, leading authorities in midge identification.

Raymond and Junichi were able to connect these adults (Figure 4) to the maggots that we had been observing in soybean fields. The identification of the adults will be critical for monitoring their emergence next spring in fields where there was a problem the previous year. Producers, consultants, and other ag professional are encouraged to follow UNL CropWatch or the authors on Twitter (@justinmcmechan, @BobWrightUNL) for updates on soybean gall midge emergence this spring.

Little to no information is available on soybean gall midge. As of now, soybean gall midge has only been identified to the genus Resseliella which encompasses 55 species worldwide, 15 of which have been identified in the United States. None of these species are known to occur on soybeans. DNA and morphological comparisons conducted by Junichi and Raymond indicate that it is likely a new species.

Figure 3. Darkened area at the base of a soybean plant (A) associated with soybean gall midge. Peeling back outer layer reveals large numbers of soybean gall midge larvae (B). Less developed larvae appear white in color until 3rd instar (C).

Management Practices

Studies with management practices such as planting date and soybean maturity group were evaluated for soybean gall midge damage at the Crop Management Diagnostic Clinic plots at the Eastern Nebraska Research and Extension Center near Mead. These plots are used for demonstration purposes and are not replicated. Soybeans were planted every three weeks beginning in late April through the end of June. Each planting date consisted of four maturity groups (1, 2, 3 and 4).

Dissections of random plants from each plot showed that all maturity groups within each planting date were infested with the exception of a late June planting date. This matches observations of later planted soybean fields in Iowa and South Dakota having reduced visual symptoms and lower infestation rates. Maturity groups 1 and 2 showed visible signs of damage at or near the soil surface whereas groups 3 and 4 showed signs of plant damage in the axils of the trifoliate approximately 6-8 inches from the soil surface.

Figure 4. Adult soybean gall midge collected from emergence cages at the Eastern Nebraska Research and Extension Center near Mead on August 2, 2018. Adults are approximately ¼ inch in length with an orange abdomen (not visible under the wings). A key characteristic is the black and white banding on its legs. (Photo by Justin McMechan)

Yield Losses

In heavily damaged fields, losses associated with soybean gall midge are inevitable due to the number of dead or dying soybean plants. Damage to the phloem and xylem of the plant is likely to result in yield reductions for surviving soybean gall midge infested plants. Additional losses are also anticipated due to the lack of stem strength, predisposing plants to increased risk of lodging if harvest is delayed. Yield loss estimates on a small sample of plants from a heavily damaged field indicate nearly complete yield loss from the field edge up to 100 ft., with about a 20% yield loss 200 and 400 ft. from the field edge.

Source: unl.edu