By Erin Hodgson and Ashley Dean

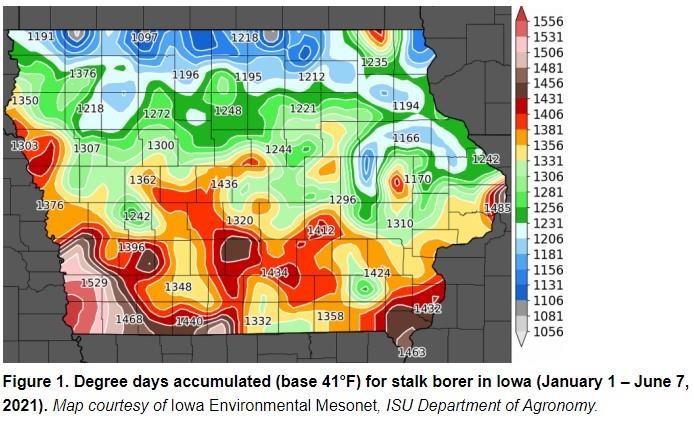

Stalk borer is an occasional pest of corn, but it can be persistent in some fields, especially those fields near fence rows, terraces, and waterways that serve as overwintering sites. Tracking degree days is a useful tool to estimate when common stalk borer larvae begin moving into cornfields from their overwintering hosts. Foliar insecticide applications are only effective when larvae are migrating and exposed to the insecticide. Start scouting corn for larvae when 1,300-1,400 degree days (base 41°F) have accumulated. Much of Iowa has reached this important benchmark (Figure 1); therefore, scouting for migrating larvae should begin now to make timely treatment decisions.

Figure 1. Degree days accumulated (base 41°F) for stalk borer in Iowa (January 1 – June 7, 2021). Map courtesy of Iowa Environmental Mesonet, ISU Department of Agronomy.

Figure 1. Degree days accumulated (base 41°F) for stalk borer in Iowa (January 1 – June 7, 2021). Map courtesy of Iowa Environmental Mesonet, ISU Department of Agronomy.Management

Female moths prefer to lay eggs in weedy areas in August and September, so managing weeds (especially smooth brome and giant ragweed) within the field can help make fields less attractive. Small grain cover crops may also be a potential egg-laying site. Additionally, long-term management requires mowing grassy edges and roadsides around fields so that females will not lay eggs in that area during the fall. Mowing, burning, or using herbicides on grasses and weeds in field margins, terraces, and waterways while stalk borers are active (between planting and July) will only force them to move to nearby crops.

Stalk borers tend to re-infest the same fields, so prioritize scouting fields with a history of stalk borers, paying extra attention to the field edges. Finding “dead heads” in nearby grasses or weeds is an indicator of stalk borers in the area. The larvae are not highly mobile and typically only move into the first four to six rows of corn. Young corn is particularly vulnerable to severe injury; plants are unlikely to be killed once they reach V7 (Photo 1).

Photo 1. Stalk borer larvae can shred corn leaves and destroy the growing point.

Photo 1. Stalk borer larvae can shred corn leaves and destroy the growing point.No rescue treatments are available for stalk borer, but tracking degree days and scouting the field can determine whether larvae are present and still migrating. Once larvae have bored into the stalk, an insecticide will not reach them. Larvae excrete a considerable amount of frass pellets in the whorl or at the entry hole in the stalk, which is a good indication that larvae are present. Also, look for new leaves with irregular feeding holes that may indicate the presence of larvae. Look for larvae inside the whorls and determine the percentage of plants infested. Young larvae are a distinct brownish-purple color with three prominent stripes at both ends of the body and a purple band in the middle of the body that disrupts the stripes on the sides (Photo 2). Fully grown larvae are uniformly gray and may be up to 2 inches long.

Photo 2. Identification features of a young stalk borer larva. Photo by Adam Varenhorst.

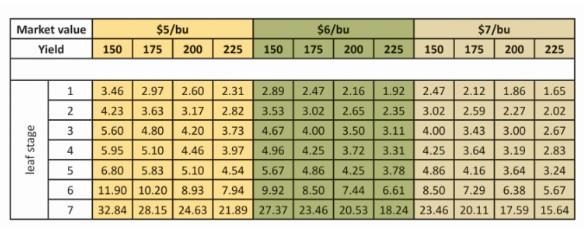

Photo 2. Identification features of a young stalk borer larva. Photo by Adam Varenhorst.The use of an economic threshold (Table 1), first developed by Iowa State University entomologist Larry Pedigo, will help determine justifiable insecticide treatments based on market value and plant stage. Young plants have a lower threshold because they are more easily killed by stalk borer larvae.

Table 1. Economic thresholds (expressed as percent of infested plants) for stalk borer in corn, based on market value, expected yield, and leaf stage.

Table 1. Economic thresholds (expressed as percent of infested plants) for stalk borer in corn, based on market value, expected yield, and leaf stage.If an insecticide is warranted based on stalk borer densities, the application must be well-timed to reach exposed larvae before they burrow into the stalk. Target applications at peak larval movement, or 1,400-1,700 degree days (base 41°F, beginning January 1). Applying insecticides after larvae have entered the stalk is not effective. Since larvae are not highly mobile, consider border treatments. Make sure to read the label and follow directions, especially if tank-mixing with herbicides, for optimal stalk borer control.

Source : iastate.edu