By Sjoerd Willem Duiker and Kyle Alexander Imhoff

The crop water balance equation states:

Precipitation (P) + Irrigation (I) = Runoff (R) + Deep Drainage (D) + Evaporation (E)+ Transpiration (T) ± Soil Water Content (∆S).

The water balance equation considers the crop and soil as a box with inputs and outputs, the inputs being P+I and the outputs R+D+ET and ∆S soil water in the root zone a storage component. The components of the water equation are expressed in units of depth (such as inches or cm of water). In the previous issues we discussed R, D, E, T and ∆S and today we will wrap it up with a discussion of our climate with a focus on precipitation, and how it is expected to change in the future.

Annual precipitation averages roughly 40 inches in Pennsylvania, although it varies between regions (Figure 1). Air movement is typically from the west to the east, so clouds will move in that direction most of the time. Orographic effects (lifting and lowering of airmasses when air flows over mountains) cause higher precipitation west and lower precipitation east of the Allegheny mountains, and higher precipitation in the Poconos. The effect of large water bodies can also been seen - Humidity from Lake Erie causes increased precipitation in the northwest, while the effect of proximity to the Atlantic Ocean results in higher precipitation in the eastern part of Pennsylvania.

Figure 1. 30-yr average annual precipitation in Pennsylvania.

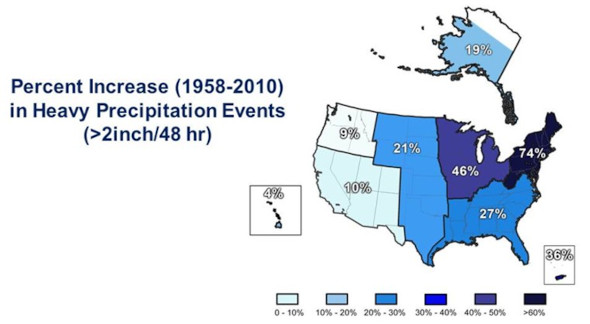

Precipitation includes snow, hail, and rain and its distribution over the year matters too as any farmer knows, as our soils can only hold so much water to help our crops survive from one to the next precipitation event. Precipitation is relatively evenly distributed over the months of the year, but because it is warmer, the water disappears more quickly in summer because of greater evapotranspiration. Climate scientists expect our climate to change in the future. Climate models show that we will experience higher precipitation in the northeastern United States, warmer winters so snow cover and frozen soil is likely to be less continuous, while we may expect increasingly intense rainstorms and hot dry periods between. These changes are already happening, with higher precipitation, warmer weather, and more intense rainstorms. In fact, fall and winter precipitation have been on the rise while summer precipitation has been relatively consistent over the past ~150 years Warmer, moist winters open an opportunity to make greater use of winter precipitation by growing winter grains and forages such as wheat, barley, triticale, annual ryegrass, and clovers that may be harvested or grazed. Double cropping or triple cropping may become options in Pennsylvania which can result in greater water use efficiency. While crops growing in winter may be favored, increased heat and more intense rainfall events separated by hot and dry weather will increase the risk of growing summer crops such as corn. More precipitation will result in increased challenges with soil compaction and delays in planting and harvesting. More flooding may be possible in low-lying areas and flood plains. It will therefore be important to evaluate the profitability and yield of the entire crop rotation instead of just focusing on one crop. Another aspect of the changing climate is that runoff and erosion threat is likely to increase – due to more intense precipitation events. It will therefore be doubly important to protect our soils from the impact of these rainstorms by keeping the soils covered with crop residues or living vegetation throughout the year.

Figure 2. Intense precipitation has increased in the Northeastern United States and is expected to continue to increase (Image provided — National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration via the Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell University).

In summary, we are blessed with a humid climate that makes it possible to grow crops without irrigation. But our climate is changing. Winter precipitation is increasing. Summer precipitation is becoming more intense. At the same time temperatures are inching up, causing increased risk of drought in summer. All this means that it only becomes more important for farmers in our region to find ways to get more crop for each drop.

Part 1 - the different components of the water balance and how they are affected by our management.

Part 2 - Increased yield with improved water use efficiency can be achieved by managing several soil properties.

Source : psu.edu