By Sara Bauder

It is no secret that this past fall and seemingly never-ending winter have caused many hardships for farmers. As spring (supposedly) approaches, planting comes to mind and for many, this means deciding what to do about last fall’s field ruts. There is no easy fix, but there are ways to mitigate the issues associated with ruts before planting begins.

In many cases, people assume that deep tillage is the best ‘fix’ for ruts and compaction, but in this case deep tillage may be more of the culprit than the cure. When soils experience compaction like we see in wheel tracks, a lasting impact is made, often resulting in a few inches to several feet of compaction in those areas. The degree of compaction depends on many factors, with one being how saturated the soils where when harvest occurred, as the number of water versus air filled pore spaces in the soil can change the level of compaction. Deep ruts are usually noticed first, but keep in mind that even shallow ruts of a few inches can cause issues with optimal seed depth during planting if they exceed planting depth. Regardless, when running a 20+ ton loaded combine or grain cart over wet soils, it is not surprising that compaction of any kind may happen. It is best to survey your fields and determine if your rutted areas are severe enough to effect planting before taking action.

Allow Soils to Dry

Before hooking up the tillage equipment, it is important to allow soils to dry. Attempting to repair ruts while soils are still very wet may only complicate matters. This act of ‘repairing ruts’ will work best when waiting for top soil (top 2-4 inches) to dry adequately prior to planting to avoid making issues worse with smeared, compacted soil surfaces. Essentially, if you would not plant into the soils, it is not dry enough to repair ruts.

Another helpful option for some growers may be to allow any winter annual cover crops or volunteer crops to grow up until you prepare for planting, and then chemically burn down the growing plants before no-tilling your cash crop. This can help producers looking to dry out saturated soils prior to planting this spring; however, careful management of these types of practices is needed for success. For more information on cover crops see the SD NRCS

Cover Crops Resource page.

Choose Target Areas to Lightly Till

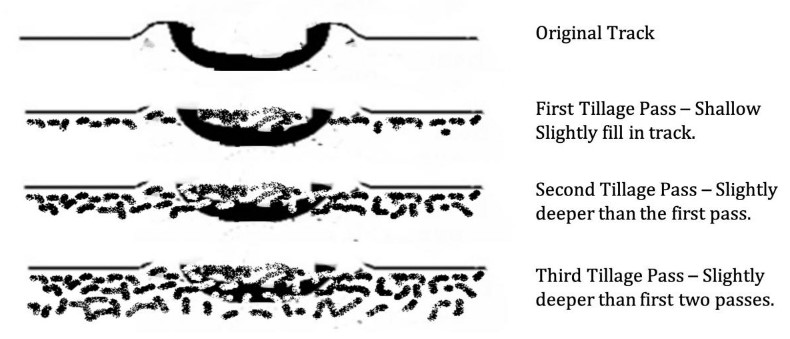

The key to repairing ruts is targeting specific areas rather than taking a pass at the entire field; essentially, make the field plantable without full width tillage. Ideally, we should shallowly fill in the areas where ruts occurred, rather than turning over the entire soil layer down to the plow pan. This type of deep tillage will reach back down into soil with excessive moisture and may cause even more compaction damage in the end. Keep in mind, that when filling in ruts, there is likely nothing growing in your soils so you are solely relying on evaporation to dry out these soils, therefore pulling up additional moisture is not going to help. Simply using a light tillage pass such as a vertical tillage tool, light disk, soil finisher, or harrow (in shallow rut cases) is going to be most ideal to fill in ruts and prevent further compaction as best as possible. In some cases, with very compacted ruts, multiple tillage passes may be needed with time (at least 2 weeks) in-between passes for drying before tilling slightly deeper than the previous pass if needed; see Figure 1 as an example of a multiple tillage pass repair. Just level the surface to make planting possible this spring and look towards dealing with any major compaction issues next fall.

Figure 1. Multiple Tillage Pass Graphic Example. Adapted from Anthony Bly.

Preventative Actions

Although we cannot change what happened last fall, some options can help avoid soil compaction and improve soil structure moving forward. In many southeastern SD fields last fall, it became apparent that some producers who had established no-till fields and followed the main principles of healthy soils were able to enter fields earlier and had minimal to no issue with field ruts as compared to conventionally tilled neighbors.

In general, tillage practices ultimately result in poor soil structure and increased compaction due to the disruption of soil particles. Moving in the direction of no-till can help producers build soil structure, giving soils a stronger shear strength and structure. These properties allow producers to get out into fields faster during wet times. However, these changes do not happen overnight and are an investment in the soil. There are many additional soil health principles that, when added to minimal soil disturbance, can greatly improve the health and productivity of soils. For more information on these topics, see the SD Soil Health Coalition

Technical Resources page.