Ag Secretary Vilsack has called for the USDA to conduct an investigation into skyrocketing costs for farm inputs, such as fertilizer and crop protection products. It begins with a 60-day comment period seeking input from stakeholders. Vilsack summed up the situation well by stating "As I talk with farmers and other stakeholders, I keep hearing significant concerns about whether large companies along the supply chain are taking advantage of the situation by increasing profits and not just passing along higher costs."

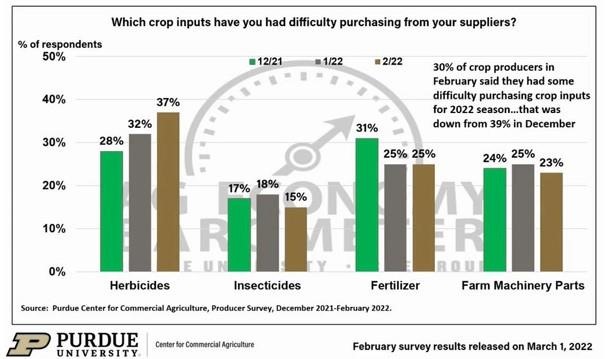

He's not blowing smoke about the scope of the problem. Purdue University polls farmers across the country monthly on a variety of key issues costing them money and sleep at night. They display results in a series they call their Ag Economy Barometer. February survey results for one of the questions asked are telling: "Which crop inputs have you had difficulty purchasing from suppliers?"

Notice that important herbicides top the list, rising even further in February, to 37% of respondents. Next was fertilizer at 25%, then farm machinery parts, and then insecticides at 15%, down just a bit from December and January readings. However, Jeff Stow, President of the online input marketplace FarmTrade.com warns the insecticide woes could still be ahead. Why? "Because a lot of farmers only buy their insecticides and fungicides as needed."

Supply crisis "explanations" sound more like "excuses" to Stow, who addressed them one by one in an interview where I asked for his take on them as one among the "stakeholders" Vilsack referenced in announcing USDA's investigation plans.

* Explanation 1: Ag chem companies focused on clearing inventory in years leading up to 2020, blaming stagnant crop prices and high costs of storing inventory. Stow told me "Here at FarmTrade, we took steps to ensure that all our vendors understood that any product they sold on our platform had to be a product they had on hand. Once the farmer buys, we move quickly to get the order on the road to him."

* Explanation 2: Tariffs rose for imported crop input products, especially post-patent chemicals. Stow told me "While true some imported products have tariffs, prices didn't rise substantially until the summer of 2021. While the tarrifs play a role in the price increases, I don't believe they are the driving force."

* Explanation 3: Freight costs and truck driver shortages created huge problems for farmer customers of companies relying on "just in time" delivery schedules. Stow's take? "Nobody can argue that's an issue for low value cargo shipped a long way. But relative to the high value of herbicides and other input products you can pack on a truck, the extra freight cost is minor compared to the price spikes we've seen blamed on them. The worst freight cost hikes have been for ocean-shipping and here at FarmTrade, we are not involved in the shipping process prior to the inputs arriving in the United States."

Most analysts see input price increases to continue through 2022

A common reason cited is the simple fact that grain prices have risen so sharply on weather problems in South America, sanctions on Russian exports and the disruption to grain exports and even '22 production prospects for Ukraine. Both of those countries are major exporters of corn, wheat and sunflower oil. In my own long experience as an ag economist, it's not "sour grapes" or "cynicism" that sees costs often less an issue than "the farmer's ability to pay" that's factored into rising prices for everything they buy.

That's been proven during times of stable energy and inflation where input prices and even farm equipment hikes exceeded cost inflation. Yet, the only thing that really explained it was higher farm income and "ability to pay." Stow says farmers are keenly aware of that and doesn't argue the point. "In fact," he says, "that's one of the things that gives a multiverse of vendors a competitive advantage over retailers captive to the price hikes passed down to them by manufacturers."

Retailers and distributors captive to price hikes "passed down from above" are even contacting Stow for products they can buy on the FarmTrade site at little more than their own wholesale cost and be assured of delivery besides. He's also had farmers ask why they can buy from their local retailer at or below the offers on his site and he immediately asks them to ascertain if their retailer actually has the product on hand or will guarantee timely delivery. I asked what happens when they do. Stow said, "Nine times out of ten they call back and say the answer was no, and stay with us."

Even prepayment doesn't guarantee delivery. I've found farmers complaining that not only are they not getting the usual discounts for pre-payment, there are often expanded "force majeure" clauses that go beyond specific reasons often referenced as "Act of God" clauses to vaguely-worded reasons like "unforeseen extraordinary circumstances." I asked Stow how they handle that. Answer: "That's why we insist inventory sold be inventory on hand. Further, not only is that a rule from FarmTrade, it's sort of a moral code among our sellers as well. It is not an iron fist that runs our business. It's our sellers' a deal-is-a-deal attitude. We are rarely forced to remove a seller, because the ones on our platform are trustworthy and honorable."

Are farmers themselves "hoarding" unneeded inputs for resale? I've read ag chem companies in short supply actually contacting farmers to offer re-purchase and asked Stow about that. "We did see some farms selling back chemicals, like glyphosate as they doubled in price, only to see them continue to rise. But even though all sellers on FarmTrade must have a chemical dealer's license, we refer farmers with unneeded inventory to retailers we know are looking, but see very little of this going on now."

Experts say the "Digital Age" offers some hope. I've read some mentioning how labor shortages, for example, are changing how agricultural companies operate, including input suppliers. They cite efficiencies in online order entry, order tracking and warehouse management systems. Stow couldn't agree more. His platform pioneered online purchasing of farm inputs a la today's "Amazon" model in 1999 when Amazon itself was just 5 years in business and just moving from book selling to book publishing.

Farmers pooling orders can win volume discounts. Another big competitive advantage of their business model, according to Stow, is their ability to "bundle" shipments among many different retailers on their platform. Manufacturers won't "break a pallet" for a buyer, but retailers with offerings on their platform will. He's finding yet another way to save farmers money is to facilitate "pooling" of their orders to win volume discounts normally limited to only the largest operations.

CLOSING COUNSEL? Waiting for lower prices has a poor reward:risk ratio. Interviewed by DTN's Emily Unglesbee, Rabobank Executive Director of Research Sam Taylor, told her "Almost all the flex in the supply chain is now gone … everything that might not have had an impact on the supply chain in the past is now going to because of the length of delays that have built up ... farmers have to be cognizant of scarcity."

Stow totally agrees. "The days of controlling inventory expenses with 'just in time' delivery are over for the foreseeable future. Now having inventory on hand is an asset, not a liability. That's why we insist on it among our vendors. Waiting until the last minute in hopes of lower prices is rolling the dice and, in this environment, the dice are loaded against you."

Source : AgPR