By Alyssa Collins and Paul D. Esker et.al

As the wheat begins to flow through the combines in Pennsylvania, many growers are noticing depressed yields and quality issues compared to their expectations. This more modest harvest is not entirely surprising if we recall reports from the regional wheat tours earlier this month.

So, what is causing this in 2024? There are several contributing factors, and they likely differ by location. Let’s explore a few here.

Environmental Conditions

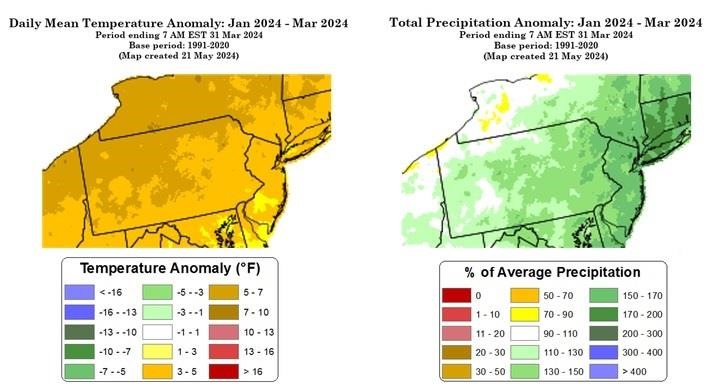

Above-average temperatures and rainfall during the 2023-2024 Winter season were common in many regions of Pennsylvania, while other locations only experienced warmer-than-average temperatures (Figure 1). These conditions were conducive for a faster growing degree-day accumulation and early head development across much of the growing area. For example, in our integrated management trials for Fusarium head blight (FHB or scab), we observed that flowering was from 5-10 days earlier than in previous years.

Figure 1. Left map -Temperature Anomaly: January - March, 2024. Right map - Total Precipitation Anomaly: January - March 2024.

In the Spring, warm daytime temperatures may have caused the plants to push lush, vulnerable growth, and when nighttime temperatures plummeted, sensitive tissues (e.g., flag leaf) were injured. Impacts on yield from such conditions vary considerably among different varieties and even the same variety planted just a few weeks apart. Yield losses from frost injury are greatest when frost occurs between heading and flowering. In some cases, abiotic stress can cause the head to appear completely bleached, which may be confounded with FHB symptoms during grain filling, when the plant is still green. If the head was aborted due to abiotic stress, the stems will also be completely bleached, whereas if the cause was FHB, the stems will be green. Warm and moist conditions in the winter and early spring may also have caused excessive tillering which can promote competition between tillers and result in a higher proportion of unproductive tillers (tillers not bearing a head). In this year’s wheat tour, we observed that almost all fields had less than 3 million heads per acre (typically required for optimum yield) despite timely planting and appropriate seeding rates in most cases.

Disease

Development of FHB is all about timing of plant development and environmental conditions. In other words, if the weather is favorable for the fungus in the weeks just prior to crop flowering, infection increases. In addition, if you missed the window to spray a FHB fungicide at the beginning of wheat flowering, infection goes up. In some regions of Pennsylvania, these two events coincided, and the result may be higher than expected levels of scab. Those farmers who applied a timely spray to at-risk small grains may still see some symptom development. This is because even the best products applied at the perfect time (at the onset of flowering) do not give 100% protection. At best, these fungicides combined with a moderately scab-resistant variety can offer a 50-80% reduction in disease severity and, ultimately, mycotoxin production. If a spray was applied before flowering, disease control will be even less. If the variety being grown was genetically susceptible to scab, disease levels can be high. Those who see scab in their crop naturally worry about elevated levels of deoxynivalenol (DON), but do not panic yet. The fungus does not always produce these chemicals and hot, dry conditions during ripening may have halted disease progression in some areas. Visit our recent article to learn more about assessing your level of FHB and what to do about it.

Other diseases that were observed in localized areas this season include Pythium root rot (a stand and vigor reducer), Stagonospora glume blotch (a yield reducer), sooty mold (quality reducer) and barley yellow dwarf disease (a virus that causes underdevelopment and yield loss).

If you are interested in a deep-dive into mycotoxin management in other crops, plan to join us July 22 for a workshop in Sugarloaf, Luzerne County.

Source : psu.edu