By Brad Carlson

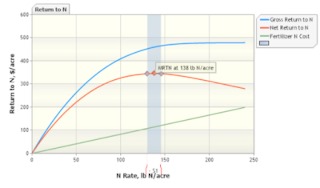

Nearly 20 years ago, Minnesota, together with many other states in the North Central region, adopted the Maximum Return to Nitrogen (MRTN) system for determining optimum nitrogen (N) rates for corn. Despite all of these states using the same system, the N rates the system produces for different states vary from state to state. This post explores the reasons behind these differences and why the MRTN system works the way it does.

What is the Maximum Return to Nitrogen (MRTN) system?

The MRTN system combines data from N response trials with the economics of N price and crop value. Every state that uses this system has shown that optimum N rates do not increase in a linear fashion as yield increases. This means that for a given area or year, the optimum N rate is likely the same whether the maximum yield is 180 bu./ac or 250 bu./ac. To many farmers this seems counterintuitive, however there are mountains of research data to support this. Those who have dug into this phenomenon quickly learn that the factors that limit yield are more related to climate and soils than to N rate.

The current recommendations can be found using the corn nitrogen rate calculator. The system is “alive,” meaning the optimum N rates change regularly when new research data is added into the system.

Why do N rate recommendations differ from state to state?

When using the N rate calculator, it doesn’t take much effort to discover that optimum N rate recommendations differ from state to state. While some criticize the system, or their home state, because the local research is different from a neighboring state, the reason there are differences is very simple, and it is the exact same reason why optimum N rate does not correlate to yield: different states have different climates and soils.

The fact that the system is the same across states was based on a desire to unify how rates are established. It was always understood that there would be differences in optimum N rates from state to state due to differences in climate and soils. Everyone knows that it is warmer, on average, as one moves south. Furthermore, most know that average precipitation in this region increases as one moves from west to east. This is why Minnesota has lower optimum recommended N rates than Iowa or Illinois.

The primary reason why high-yielding environments do not respond to ever-increasing N rates is due to the soil’s ability to supply the crop with N. Soil does this by mineralizing organic matter (OM). While this process is very complex and hard to predict, a basic reality is that when there are higher levels of organic matter, the soil has a greater ability to supply mineralized N. Large portions of Minnesota’s prime agricultural soils have 3% - 4% or even higher levels of organic matter. Organic matter levels decrease as one moves south due to warmer and wetter climate conditions. It is common for soil types found in southern Minnesota to have 3.5% OM, while the same soils in central Iowa have 2.5% OM. A typical soil in central Missouri or southern Illinois will have 1.5% OM or even less. This is one reason why optimum N rate recommendations increase as one moves south.

Nitrogen is mobile in the environment and subject to leaching or denitrification when soils are saturated. N that is mineralized late in the growing season, or after the crop matures, is subject to be lost prior to next year’s growing season because of these processes. Leaching and denitrification also put pressure on N fertilizer that is applied. These processes essentially “suspend” when the soils are frozen in the winter. It is simply intuitive that leaching and denitrification has more time to happen the farther south one goes. This is further exacerbated by the fact that denitrification (when N is lost to the atmosphere) is a microbial process that is temperature-dependent, again favoring higher N loss the farther south one goes. The potential for N loss is another major factor leading to N rates increasing as one moves south and east.

Source : umn.edu