By Craig Sheaffer and Nathan Drewitz et.al

Cereal winter rye is used in Minnesota as a winter cover crop following corn or soybeans. Because it's very winterhardy, it has the potential to reduce soil erosion and scavenge excess soil nutrients when used as a cover crop. Winter rye also can be used as an early spring forage source. While it has high yield potential, harvest timing must be managed carefully to obtain the desired forage nutritive value.

Maturity affects yield and quality

Maturity at harvest affects winter cereal rye forage yield and nutritive value. To obtain both reasonable forage yields and quality for hay and haylage systems, harvesting at boot stage is recommended. Boot stage is just before seed head emergence when the head can be felt near the top of the last leaf.

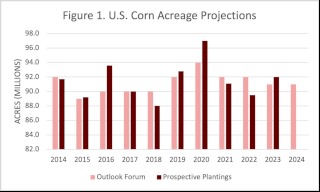

Figure 1. Winter rye forage yield at six growth stages (21=tillering,

31=stem elongation, 41=boot, 51=head emergence, 61=anthesis,

81=dough). Results averaged for two varieties and three locations

in southern Minnesota. Source Kantar et al., 2011.

As rye maturity advances from vegetative stages in May to flowering in early June, forage yield increases (Figures 1-3). In contrast, forage nutritive value, including crude protein and digestibility, decrease. Relative feed value likewise declines from 150 at leafy vegetative stages to about 100 at the boot stage.

Figure 2. Winter rye forage protein concentration at six harvest growth stages (21= tillering, 31=stem elongation, 41=boot, 51=head emergence, 61=anthesis, 81=dough). Source Kantar et al., 2011.

Figure 3. Winter rye forage digestibility at six harvest growth stages (21= tillering, 31=stem elongation, 41=boot, 51=head emergence, 61=anthesis, 81=dough). Results averaged for two varieties and three locations in southern Minnesota. Source Kantar et al., 2011.

Until boot stage, rye forage can be used in rations of growing heifers and lactating cows. However, rye forage RFV and energy content decline rapidly after boot and is best suited for maintenance diets or for use as a fiber source in higher energy diets. Rye can also provide a high-quality forage when grazed during vegetative stages and will regrow for an additional harvest at boot stage. For accurate measurement of nutritive value, test forages at a forage testing laboratory.

Changes in forage yield and nutritive value are closely related to increases in the stem and inflorescence fractions of the forage while the leaf proportion decreases. Stem quality is significantly lower than leaf quality because of high levels of lignin and structural fiber. Grain formation can increase the energy portion of the forage. Results shown in Figures 1-3 were from St. Paul and Morris (Kantar et al., 2011), but forage yield potential can vary depending on weather conditions, latitude, fall planting date and soil fertility. For example, forage yield decreased when planted after September and increased by N fertilization.

Maturity effects on mineral content

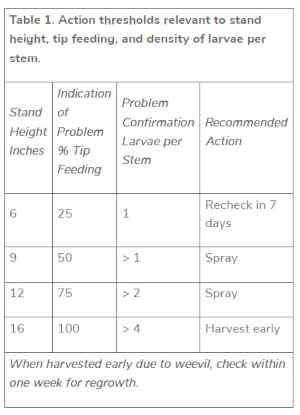

Mineral contents for cereal rye forage at several developmental stages are shown in Table 1. Concentrations of nitrogen (N) and potassium (K), the most prevalent minerals, show the greatest decrease with maturity. Changes in other mineral concentrations are small. The mineral concentrations are adequate to meet the nutritional requirements of most ruminants.

However, high levels of K in dairy cow diets before calving can cause milk fever. This is also known as hypocalcemia or low blood plasma Ca levels at the onset of lactation. Rye is efficient in extracting soil K, and as a result, its forage K levels can routinely be over 2%. This can predispose cows to milk fever regardless of the forage calcium (Ca) level.

Table 1. Concentrations of minerals in cereal rye forage at several developmental stages when harvested at a 4-inch height. Results from several locations in Iowa (Dahlke, 2019).

N= nitrogen; Ca=calcium; P=phosphorus; Mg=magnesium; K=potassium; S=sulfur

Nutrient scavenging

Winter rye is noted for its ability to remove nitrogen from the soil that remains after an annual crop. Nutrient removal is a function of not only nutrient concentration but also forage yield. Using data shown in Table 1, each ton of forage harvested at the boot stage removes 76, 6, and 76 lb/acre of N, P, and K, respectively.

Source : umn.edu