By Bernt Nelson

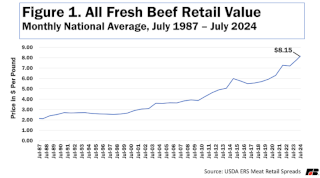

USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) reported record retail beef prices for the month of July, with the all fresh value of beef estimated at $8.15 per pound (Figure 1). This marks the first time in history the national average price for all fresh beef moved above $8. Consumers across the country are asking, “Why is beef so expensive?” The answer to this question has been several years in the making. This Market Intel will break down the events that have led to record beef prices in the United States and explain how farmers, despite these record prices at the grocery store, are more vulnerable now than ever.

The Story – Drought, Inflation and Inventory

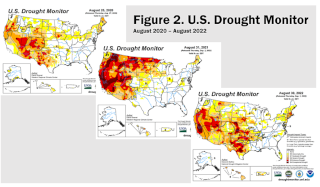

Pasture conditions began to deteriorate across the United States in 2020. The La Niña-driven drought would press on for the next three years causing pasture conditions to deteriorate and sending prices for feed grains to record levels (Figure 2). At the same time, inflation began to rise, driving up costs for everyone in the United States, including farmers and ranchers. The combination of drought and high input costs compelled farmers to place a higher-than-normal percentage of female cattle on feed for slaughter, rather than keeping them for replacement breeding, resulting in increased short-term beef production but contraction in the cattle inventory.

This contraction has led to the smallest cattle inventory in 73 years and a reduction in the U.S. beef supply. The cattle inventory takes more time to rebuild than other livestock inventories because it takes 18-24 months from a calf’s birth until it is fed to slaughter weight and ready for market. For cow-calf operations, where farmers breed cattle and sell the calves, once a female calf is held back for breeding purposes – rather than sent for feeding and slaughter – it takes about a year before that cow produces a calf that is added to the cattle inventory. Fewer cattle on feed in the long run will result in more upward pressure on beef prices. Retail beef is already hitting record prices, but ranchers have not yet begun holding back females so retail beef prices are likely to climb higher.

Cattle on Feed

This year has been an anomaly with regards to cattle on feed. Despite a lower cattle inventory and higher prices, the number of cattle on feed has remained elevated. According to the latest Cattle on Feed report, released on Aug. 23by USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), there were 11.1 million cattle on feed on August 1, up slightly from 2023. Placements were 1.7 million head, up about 6% from 2023. This is a strong number for placements and indicates that the inventory of cattle on feed will remain strong through the third quarter of 2024, keeping prices from rising dramatically until the number of cattle on feed begins to decline. USDA cancelled the July 2024 Cattle Inventory survey for budget reasons, so the exact size of the calf crop is unknown; but it is expected to be near record lows, which means when the current supply of cattle available for placement on feed dries up, there will be fewer calves coming to fill feedlots.

Cash prices offered by packers dropped substantially over the last couple of weeks. Feed grain prices are down about 25% in 2024, which has incentivized placing more cattle into feedlots as well as keeping them on feed longer. This large quantity of very heavy cattle available in the short run has resulted in a short-term reduction in price that allowed packers to secure a lot of fed cattle at a low price while selling for a high cutout (processed and boxed beef) value. Marketings of fed cattle in August were 1.855 million head, a strong number that shows that the packing sector has been able to aggressively buy cattle when markets are edging downward to help secure profitability. Packers are gaining from high grocery store beef prices, while farmers are losing from the drop in price packers pay them.

Cold Storage

NASS’s Cold Storage report, which provides data for the national stocks of meats, dairy products, fruits and vegetables in public, private and semi-private warehouses, shows the supply of all meat products in the survey decreased from the previous month. Beef, pork and lamb are all down year-over-year, while poultry meat in freezers is up about 2% from July 31, 2023. More specifically, the latest report, released on Aug. 23, estimates that total red meat supplies on July 31 fell 3% from the previous month and 3% from July 31, 2023. Beef supplies were down slightly from the previous month and down about 1% from July 31, 2023. Keep in mind, while beef in cold storage is only down 1% from one year ago, it’s down about 20% over two years from July 31, 2022. This decrease in supply when paired with strong domestic demand provides a snapshot of why consumers are seeing record beef prices in grocery stores.

Obstacles to Expansion

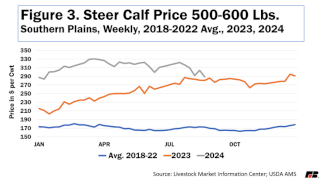

One of the positive results of lower cattle supplies is higher prices for ranchers. However, higher prices do not affect all farmers and ranchers equally, especially during an economic downturn in agriculture. The national 5 area market average weekly fed steer price for all grades for the week of Aug. 25 was $185.54/cwt, up just 1.5% from the same week in 2023, but 56% higher than the 2018-2022 average. The weekly average price in the southern Plains for 500-600 medium and large steer calves for the week ending Aug. 25 was $288.91/cwt, up 3% from $280.65 during the same week in 2023 and 67% higher than the 2018-2022 average (Figure 3).

While prices have come up, so have expenses. According to ERS’ February 2024 Farm Sector Income Forecast, production expenses in all of agriculture are forecast to increase 4%, or $16.7 billion, in 2024 to reach a record-setting $455 billion. This marks the sixth consecutive year of production expense increases, and the fourth consecutive year production expenses have hit a new record high (and the updated numbers to be published on September 5 are expected to show an even worse bottom line for American farmers.)This rise in prices combined with the lingering effects of drought and higher production expenses, provided farmers incentives to liquidate cattle rather than trying to hold on.

Higher prices are helpful if a farmer is selling calves or getting out of the business. But what about when they are trying to buy, expand or buy cattle to get started? While higher prices benefit the seller, they make things hard for the buyer. This perspective, along with the current financial conditions in the overall farm economy, makes it difficult to predict when expansion in the cattle industry will happen again.

The Farmers’ Perspective - Why We’re Not Expanding

According to USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture, the average age of a farmer rose from 57.1 years old in 2017 to 58.5 years old in 2022. Put yourself in the shoes of the aging farmer or rancher. Prices are high enough to make money from sales. Expanding might require borrowing at the unusually high current interest rate and paying top dollar to buy any additional cattle. Selling cattle avoids these extra costs and time needed to pay off debt and gives the farmer a good price for his or her cattle. This makes selling some or all of the herd a tempting proposition.

The same factors are also obstacles to new and beginning farmers. Livestock used to be a way for new and beginning farmers to get into farming. Rather than having to buy expensive equipment and land involved with crop production, a new farmer could start out with a few cows and limited resources and build their herd, purchasing additional resources over time as needed. My family’s farm in North Dakota got its start in livestock this way. Two orphaned calves were purchased, bottle fed in a neighbor’s barn and later sold.

Click here to see more...