The farm bill is already a year late, the stakes are high and time is running out.

The law from which USDA takes its marching orders is supposed to be revised and renewed every five years. The last five-year farm bill expired with September 2023, so American agriculture has been working under a one-year extension of a six-year-old law. Though it was a good farm bill at the time, there are a lot of pieces of this 2018 law that are badly in need of an update. Six years of tumult – including the highest inflation in 40 years, geopolitical disruptions to markets for the things that farmers sell and the things they buy, and rising expectations for what farmers can and should do for the planet – have left key parts of the 2018 farm bill outdated. The world is undeniably different than when the last farm bill was written.

Here is a short list of things that farmers – and all of us – will miss out on if an update doesn’t happen this year:

1. Farmer Safety Net: The safety net for farmers includes support when prices fall to unsustainable levels. This helps farmers get through the bad years so they can continue producing the food, fuel and fiber that America – and the world – relies on. There are many multi-generational farms and many rural communities that have thrived through the years thanks to an occasional assist from USDA.

One part of this safety net is the crop insurance program, which is a permanent program that wouldn’t go away without a new farm bill, but which needs some improvements to make it more affordable to all farmers.

Unfortunately, a big part of the farmer safety net is tied to the renewal of the farm bill and, more unfortunately, depends on a set of relatively fixed “reference prices” for key crops.

The Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programs provide so-called “shallow loss coverage” for farmers’ losses not covered by crop insurance. Reference prices are important in both programs, but are the key trigger for PLC.

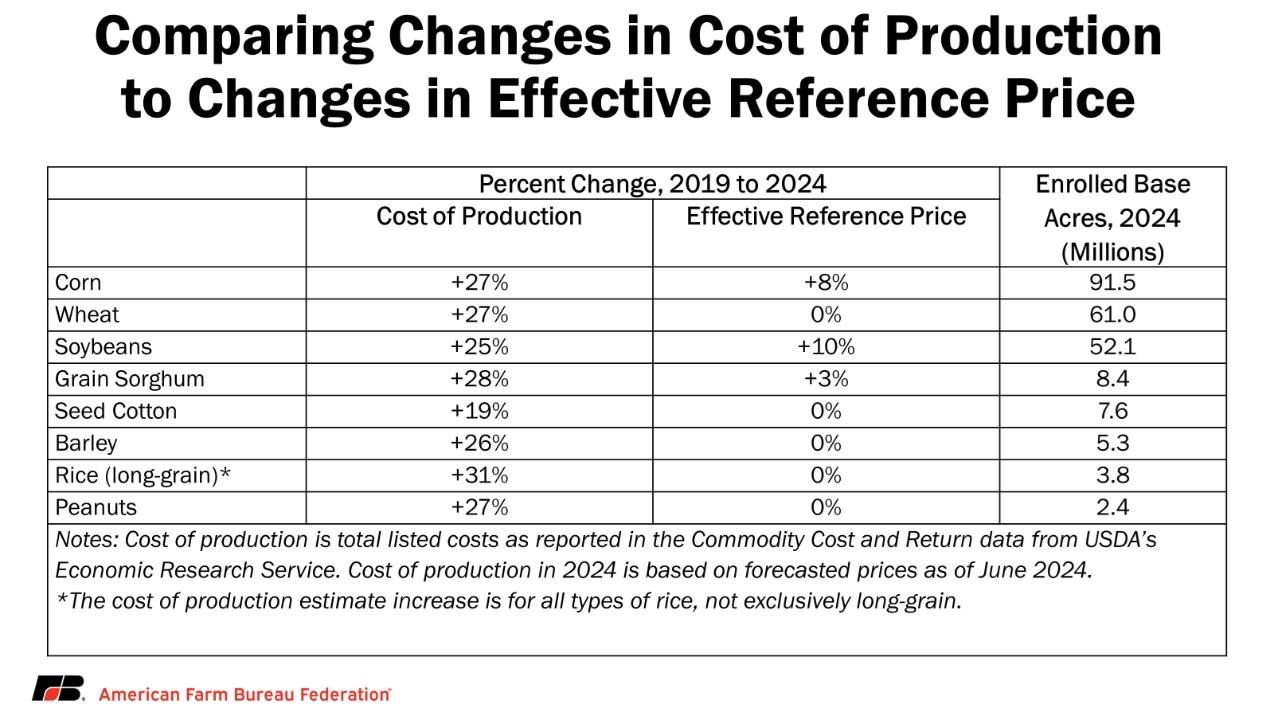

Fundamentally, the fixed “statutory reference prices,” which were set in 2014, do not account for unforeseen market forces, such as the exceptional inflation in recent years. The inflation of the last few years has raised costs and market prices but left this safety net so close to the ground that it provides little or no protection for many farmers. Adjusting these prices, or the formulas that use them, is necessary just to make these programs do what they were intended to do a decade ago.

A price escalator was added in the 2018 farm bill based on recent years’ market prices; but the resulting effective reference prices (ERP’s) have not kept up with crop and input price increases, cannot be expected to keep up with long-term trends, and are ultimately capped at 115% of the statutory reference prices. In fact, by 2023 the escalator had only successfully raised the effective reference price for eight of the 23 eligible crops, the largest of which is temperate japonica rice, which only accounts for 343,227 acres in 2024 (0.1% of enrolled base acres). It is evident that the price escalator has not worked as intended, at least not quickly enough to keep up with the massive farm cost inflation of recent years.

The following table shows the percent change in the cost of production of the eight largest commodities by base acre enrollment between 2019, the first year the price escalator went into effect, and 2024, when the price escalator finally kicked in for three major crops (corn, soybeans and sorghum).

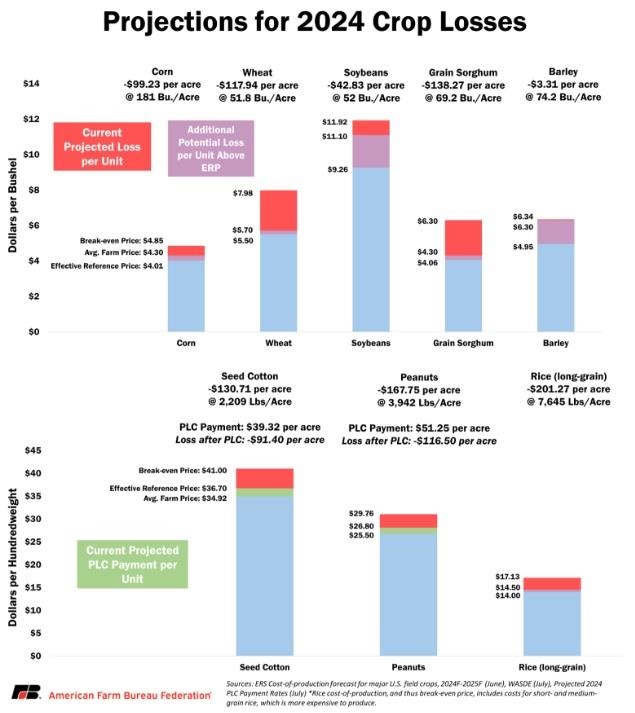

The graphs below illustrate the failure of the current outdated reference prices to address farmers’ financial pain in a down year. They show the ERP’s for 2024, USDA’s projected market year average price, and a break-even price derived from USDA’s cost-of-production forecasts. Of the eight largest covered commodities shown above, all are facing losses this year ranging from -$201.27 per acre for rice to -$3.31 for barley. At current ERP levels among the top eight crops, the PLC program will only trigger for peanuts and seed cotton, the crops facing the second- and third-largest losses per acre, respectively.

(ARC-County is triggered by county-level crop revenues calculated in formulas less tied to reference prices, and may be activated for various county-crop combinations across the country in 2024.)

This year is shaping up as a painful demonstration of the need for higher reference prices. While input prices have eased slightly since post-pandemic highs, commodity prices have been falling at a much faster rate. With sinking commodity prices and stubbornly high input prices, farmers are taking a hit while they wait for Congress to act.

2. Help for Dairy Farmers: When markets turn against them, dairy farmers also rely on occasional help through the Dairy Margin Coverage program, which they help pay for. Anticipated improvements in this program include opportunities to buy coverage for a higher nominal milk-over-feed-cost margin that would cover some (but not all) of the inflation of the last six years.

In 2018, the average farm produced about 5 million pounds of milk, while today the average farm produces over 8 million. So dairy farmers are also hoping to increase the amount of a farm’s annual production that gets extra risk coverage from 5 million to something closer to their average size today.

USDA recently proposed giving a large share of the value of milk priced in the federal milk marketing orders over to processors, based on a questionable voluntary processing cost survey. This would reduce farm milk prices by about 5%. Dairy farmers are counting on the farm bill to direct USDA to make an audited and mandatory survey of milk processing costs, to ensure the fairness of milk price formulas used to price most milk in the U.S.

By delaying the farm bill another year, Congress would be delaying help that could slow the rate of dairy farm consolidation.

3. Agricultural Sustainability: Most farmers and ranchers live and raise their families on the land that they work, often for many generations, so they naturally care for the land. But expectations have risen, and farmers are increasingly being asked to make up for the environmental impacts of the rest of us. The Inflation Reduction Act dedicated many new federal budget dollars to conservation programs aimed at helping farmers support their own land’s sustainability, as well as the sustainability of the global environment, but over a limited time period. There is an opportunity to incorporate those IRA conservation and climate dollars into a new farm bill and make it part of Congress’ permanent baseline for future farm bills.

This infusion of conservation funding is particularly important because the farm bill budget baseline without it is based on a fixed nominal amount of money being available. Like the safety net programs discussed above, conservation programs are defined by that fixed amount; and like those safety net programs, their value is eroded by inflation.

During the one-year farm bill extension that ends with the 2024 fiscal year in September, over $2.7 billion of this IRA money is projected to be spent outside the farm bill, and so won’t be available for future farm bills, by congressional budget rules. Even more is likely to be spent in fiscal year 2025. Getting a farm bill passed is the simplest, and maybe the only way, to convert the one-time limited spending for sustainable agriculture into a long-term commitment. Every year of delay means billions of dollars lost to future programs.

Boosting conservation funding for agriculture is critical to supporting agriculture’s contribution to the global environment.

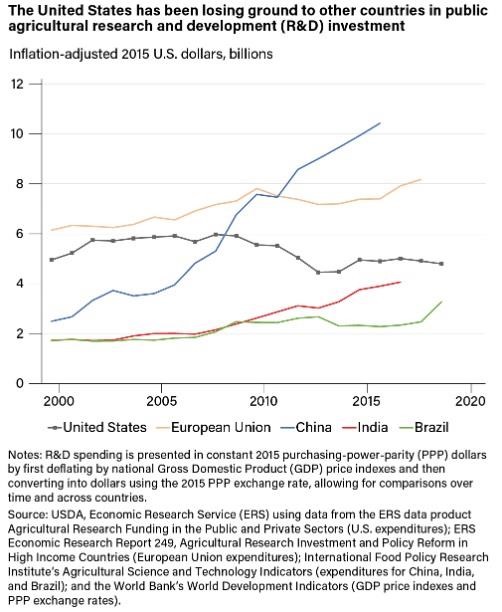

4. Research: Even more critical to the sustainability of agriculture – and to its capacity to clean up the planet – is growing agricultural productivity. Farmers are being asked to do more with less, but this depends on having the technology to do that. A lot of good research is done in the private sector, but much critical work depends on publicly funded research by government agencies and universities. The most productive wheat varieties, for one example, were developed with public research funding and are freely available, because it has historically been difficult for seed companies to cash in on wheat improvement investments.

The United States has been falling behind the rest of the world’s major agricultural producers in our public investment in agricultural research. In real terms, our public investment in agricultural research has fallen by more than a third since 2002. China, in particular, spends more than $10 billion a year on agricultural research, twice what the United States public sector is spending. In fact, China's public research expenditures alone are almost as much as those of the U.S., India and Brazil combined.

Commitment to agricultural research in a new farm bill could provide new investment in research facilities, a boost in the search for a solution to citrus greening – which has devastated Florida’s citrus industry and now threatens California’s – and additional investment in specialty crops research.

Supporting the productivity of U.S. agriculture is critical to our competitiveness in the larger world market; it is fundamental to building our capacity to contribute to environmental sustainability; and it is absolutely necessary to supporting the health and nutrition of the world’s population.

5. Food security is economic and national security: Let us count the ways that the farm bill contributes to our security, at home and around the world.

First, the investment in agricultural research is, as discussed above, absolutely critical to the growth of production on a limited amount of land. This is the arithmetic that reconciles the needs of a hungry world with the care of the planet.

Second, helping farmers get through bad years, with commodity programs and crop insurance, keeps agricultural production capacity in business and helps ensure supplies of food (and fiber and fuel) for the nation and the world. U.S. exports are expected to make up nearly 18% of world grain trade in the 2024/25 marketing year, and a well-fed world is a safer world for all of us.

Click here to see more...