By Alvaro Garcia

Although belonging to the family Bovidae (bison, cattle, sheep, etc.), and sharing some characteristics with their ruminant cousins, goats are unique. They are represented worldwide by two genus: Oreamnos and Capra. The mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) resides in the American Northwest. The wild goat (Capra aegagrus) has a widespread distribution ranging from Europe and Asia Minor to Central Asia and the Middle East and is considered the ancestor of the domestic goat. Domestication of goats has been going on for thousands of years and it apparently started in the Persian Empire (today’s Iran), and Asia. Through centuries of selection the domestic goat (Capra aegagrus hircus) resulted to date in 165 breeds (dairy and meat) recognized worldwide. One of their characteristics is that, similar to their ancestors, they have retained the ability to thrive in harsh environments; granted, modern breeds selected for high production will need more feed than under maintenance conditions. Goats are termed browsers because of their selective feeding habits, that is they like to choose. They are also extremely fond of leaves (shrubs and trees) and thus some also label them as folivores (“leaf eaters”). However, nothing is definite with goats; if they find a nice pasture they will graze particularly relishing prickly weeds that grow in it! If these characteristics were not enough to admire, goats are also very hardy when it comes to weather extremes. They originate from environments that are very hot during the day but can be freezing at night. If there is one thing goats particularly dislike however is to get wet! There is one other aspect besides their natural biological advantages, and that is their temperament. When walking in the field they will follow their owner to a different feeding station, and enjoy this interaction in the meantime.

Why Goats in the Upper Midwest?

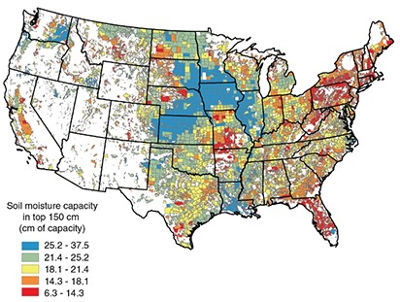

The short introduction above helps better understand why we can successfully raise goats in this region. Their adaptability to different environmental conditions makes them an excellent choice for small acreages and or land where crops do not prosper without significant investments in equipment or soil amendments. To optimize productivity and profitability without taxing the environment there is an adage worth considering: “It makes more sense to adapt the genetics to the environment than to modify this one to accommodate certain genetics”. This goes for both plant and animal genetics. For centuries man has modified the land so species less adapted to it can prosper. This practice is becoming increasingly expensive and oftentimes detrimental to the environment. The map shows that west of the Missouri river the moisture storage capacity is low compared to the east. Even during years of normal rainfall there can be short-term dry spells that affect crops.

Soil moisture storage capacity helps determine drought vulnerability.

Note: Soil moisture capacity is lower in areas with shallower soils and soils that contain high clay content. A lower soil moisture capacity limits the ability of the soil to store winter and early spring precipitations for use by crops during the summer growing months. The counties in this map are clipped to show cropland only. Source: USDA, Economic Research Service using characteristics data from USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, Soil Survey Geographic Database, 2010.

Most of the Great Plains have always been considered a semi-arid area of the U.S. This Region is characterized by hot, relatively short summers, and usually cold, dry winters. Annual precipitation increases by almost 70 percent between the Western (East of the Rockies) and Eastern ends of the Region. Potential moisture losses by evapotranspiration also increase by almost 400 percent between the Northern (Canadian border) and the Southern extremes. In addition to these moisture gradients, agricultural production is challenged by high climate variability interspersed with periods of severe precipitation shortages. Susceptibility to drought is not only determined by the yearly precipitation but also by the moisture storage capacity of the different types of soil.

Goats however can easily adapt to the variable environmental and foraging conditions of this region with only minor management strategies in order to meet their requirements. Their foraging behavior will more than likely allow them to prosper in parts of the state while they take care of most of the weeds. Granted, there will be a need for mineral supplementation as well as some grain for higher producing animals. Similarly, if forage is extremely scarce or during the winter months, hay and grain supplementation will also be needed. Fresh clean water should always be available; goats have a very keen sense of smell and will reluctantly drink dirty or off-flavored water. Finally, and as far as “accommodations” go, just remember they need protection from the rain, wind, and potential predators (dogs, coyotes, etc.).

Choosing the Right Goats

The most common dairy goat breeds registered with the American Dairy Goat Association are: Nubian, LaMancha, Alpine, Oberhasli, Toggenburg, Saanen, Sable, and Nigerian Dwarf. Choosing the right breed is more of a personal preference between milk volume, milk solids, better resistance to environmental conditions or just looks. Regardless of the decision, there are local farms that successfully keep any of these breeds in the Upper Midwest. This article is not meant to delve the advantage of each breed. It is worth noting however that Saanens are considered the “Holsteins” of the goat world because of their high milk production; Nubians and Nigerian Dwarfs on the other hand produce less milk, however much more concentrated in solids, particularly fat and protein. The remaining breeds productivity is somewhere between both extremes and varies on individual goats depending on their genetics and management. Granted, one could choose not to work with pure breeds but incorporating the desirable characteristics of two or more breeds through crossbreeding. The offspring of crosses between a breed characterized by high milk production (for example Saanen) with another with more milk solids, will usually result in animals that may produce less milk volume, but with more solids than the original Saanen. This first generation of animals will show what has been described as “hybrid vigor” with excellent production, breeding, and adaptability to their environment. Over time though, when they are crossed back to any of the two parental breeds it is difficult to maintain the positive traits of this first cross, and the productive advantages of the first crossbreds are slowly lost.

Once the decision of the breed has been made then it comes the search for the individual animals. An acceptable milk production is obviously the individual trait producers usually look for first. Since it is an inheritable trait transmitted by both parents to the doelings, it is important to verify milk records whenever possible. This does not mean that in absence of records one cannot choose animals based on their conformation and current milk production. When choosing virgin doe yearlings, it is highly recommendable to take a look at their dam and its overall conformation, particularly the udder. Udders should be adequately attached, look full when in lactation, both teats centered and of adequate size. Some does may develop disproportionally large (wide) teats, one or even both. This ends up becoming a problem when milking by hand and even with a milking machine. It is sometimes the result of kids being allowed to suckle, if they show preference for one teat over the other. A possible explanation of this preference is that a thinner teat canal in one teat that does not allow for an easy milk flow discourages the kid(s) to suckle that teat with milking accumulating in the teat cistern and progressively stretching it. Make sure kids suckle alternatively from both teats and if not, milk out the one that’s being refused. The other very important aspect is udder attachment. In lactating does udders should be adequately attached to the abdomen by strong ligaments. This is apparent in heavy producers and particularly from their second lactation on. Well-attached udders should be high, with both teat ends not surpassing a horizontal line drawn through the hocks. Extremely low udders can lead to udder or teat injuries which if deep enough can progress into fatal mastitis cases. The topline of the body should be straight (withers to rump) with some goats showing a slight slope from the withers to the rump. One other important aspect is to verify that the hoofs are trimmed regularly; badly trimmed or untrimmed hoofs can lead to painful lameness that will reduce feed intake and milk production.

If checking an adequate conformation is important, making sure the goats are free from a couple of critical diseases is crucial. If kept properly, goats are quite sturdy when it comes to ailments that may affect them. When purchasing the initial stock however, one needs to be fairly strict with a couple of diseases that they may bring with them: Caprine Arthritis Encephalitis (or CAE) and Caseous lymphadenitis (CL). The first one is viral in nature, it is specific to goats, and it is transmitted to each other via infected colostrum, milk, or blood. Symptoms are not apparent in goats except for five clinical presentations including arthritis (the most common, and usually observed after 6 months of age), encephalitis, interstitial pneumonia, mastitis, and progressive weight loss. Goats may show joint stiffness, shifting leg lameness, decreased ambulation, weight loss, reluctance to rise, and abnormal posture. Acute swelling of the joint is also possible which may lead to arthritis. The encephalitic (brain) form of CAE affects kids 2 to 6 months of age, which show signs of incoordination and inappropriate placement of limbs while walking which can progressively develop into paralysis. The interstitial pneumonia is characterized by chronic cough, labored breathing, and weight loss. In adult does mastitis can be observed usually around kidding time; it is characterized by a firm udder with difficult or no milk ejection. It is a sound practice to ask for negative CAE blood analysis tests before purchasing goats. The second disease or Caseous Lymphadenitis (CL), also called pseudotuberculosis, or just “abscesses”, is a chronic contagious disease affecting sheep and goats. It is bacterial in nature (Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis) characterized by swelling, rupture, and pus draining from affected peripheral subcutaneous lymph nodes. It can be detected by palpating enlarged lymph nodes under the skin in the angle of the mandible, right at the base of the neck and before the scapula (shoulder blade), right before the femur & tibia joint (stifle joint), and supra-mammary (above the udder) right behind the rear legs. This bacterium can survive in the environment for a minimum of one year, and it is usually spread through cuts during shearing, fences, and feeders. This disease has the potential to be transferred to humans (zoonosis) so affected animals and their lesions should be handled with surgical gloves. Treatment involves draining the pus from the abscesses and using a 7% iodine solution to flush them. Of course there are other ailments that can affect goats and that can be treated by their owner if minor or that may need veterinary attention. The two described above however, are in my opinion, the two most important to start a goat herd with the right foot.

Managing the Herd

Once the right location, breed, and animals are identified, it is time to think about how to manage the herd. Since this is about small-scale let’s assume 10 lactating does.

Let’s suppose we have decided to buy 10 alpines with an adult body weight of roughly 140 pounds each. Depending on the standing forage available, this number of animals can easily be kept in 1-2 acres of foraging area. Granted, one could have more animals (or less surface area) if they are supplemented with forage and grain. The author has kept up to 20 goats in a little less than one acre with the caveat that it was a spot with very lush forage growth with plenty of brome, reed canary grass, and other palatable forbs. There were also plenty of weeds; at least initially, since the goats gradually took care of most of them! Goats are grazed in this unfenced pasture under supervision, since the neighbor rotated corn and beans and goats were fond of both!

Click here to see more...