Dystocia and stillbirth are two common issues at calving that affect dairy cows' production and reproductive performance and cause substantial economic consequences.

Cows that had dystocia have a higher risk to develop uterine diseases, such as metritis and endometritis, which will increase the calving interval. Dystocia is defined as difficult calving due to prolonged parturition or severe assisted parturition and has been classed as one of the most-painful conditions that a cow can experience. The incidence of dystocia in the United States ranges from 9.5 to 13.2% in primiparous cows and from 5.0 to 6.6% in multiparous cows. The dystocia incidence is highly dependent on calving management, and the case definition of dystocia. Some reports classify dystocia using dystocia scores of 1 to 5, whereas other reports refer only to assisted calving, regardless of the type of assistance used (from pulling a large calf to cesarean section).

Stillbirth is defined as the death of a calf that occurs after at least 260 days of gestation just before, during, or within 24 to 48 hours after calving. Stillbirths often result in impaired reproductive and milk production and the economic losses are not limited to the value of the stillborn calf, but also the dam if she survives or not.

Understanding Risk Factors

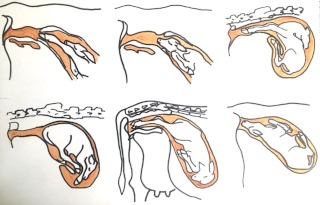

In general, dystocia and stillbirth occur when the size of the fetus is incompatible with the size of the pelvic opening of the cow, when the fetus is abnormally presented (breeched, head, or foot back), or when the cow does not experience normal parturition due to weakness, stress, or hormonal abnormalities. Dystocia and stillbirth may be caused by either maternal factors, fetal factors, or a combination of both. In most cases, dystocia is the result of abnormalities in fetal presentation, position, or posture, but it may also be caused by fetal oversized, pelvic abnormalities, or uterine inertia. Fetopelvic disproportion is a primary cause of dystocia in heifers, while fetal mal-dispositions are a major cause in multiparous cows. First-calf heifers require more assistance (19%) than higher-parity dams (11%). Holsteins are more likely to experience difficult calvings compared to Jerseys.

The various factors affecting dystocia in cattle are grouped into four main categories: direct factors, phenotypic factors related to calf and cow, non-genetic factors, and genetic factors. The first group includes malpresentations and uterine torsion. The second one includes calf birth weight, multiple calvings, perinatal mortality, cow pelvic area, cow body weight, and body condition at calving, and gestation length. Non-genetic factors affecting the risk of dystocia include: cow age and parity, year and season of calving, place of calving, calf sex, and nutrition. calf birth weight, gestation length, and whether the calf was a singleton or twin.

TWIN BIRTH

Cows with twin birth had a higher likelihood of dystocia and stillbirths than cows with single births (stillbirth for Holstein herds single births 3.2 to 5.4%, twin births 12.9 to 15.7%), the incidence of freemartinism, the overall risk of culling and perinatal mortality, and decrease milk production and cow fertility. Twin births in dairy cows are generally undesirable. The occurrence of twin pregnancies in dairy cows with high milk production is most likely caused by multiple ovulations related to low-circulating levels of progesterone.

PRIMIPAROUS COWS

The higher incidence of dystocia in primiparous cows, when compared with multiparous cows, may be due to the feto-pelvic disproportionate size of the fetus with respect to the pelvic area of the dam, influenced by the birth weight and sex of the calves (male calves were more than twice the probability of stillbirth; male calves with a birth weight over 43.7 were larger than female calves).

TIME OF CALVING

The incidence of dystocia is reported highest in winter. It is reported that calves born in winter were 15% more likely to need assistance than calves born in summer. Perhaps, because in colder winters, blood flow to the uterus increases, leading to the heavier calf. A longer dry period was associated with a higher incidence of dystocia: a dry period of more than 100 days had the highest incidence, in comparison with the lowest incidence in cows with a shorter dry period of 46 to 60 days. Cows with long dry periods are more likely to have a higher body condition (fatter). The long dry period may result in altered calcium metabolism too.

ANIMAL HEALTH

In some studies, dystocia was associated with higher blood cortisol levels, blood glucose concentrations (higher in cows who experience dystocia), and mineral imbalance (subclinical hypocalcemia). The reduction in plasma calcium levels reduce calcium stores in smooth muscle. Thus, the absence of uterine contractions, uterine fatigue, and abdominal muscle contractions may prolong the parturition process in cattle and lead to dystocia and stillbirth.

Calves born requiring any kind of assistance should automatically be considered susceptible: they are likely to have hypothermia; low blood oxygen; metabolic and/or respiratory acidosis; and impaired ability to absorb colostrum antibodies, resulting in failure of passive transfer of immunity. Dystocia calves are generally less active and have a decline in cardio-respiratory function compared to calves born easily. This impacts other body functions including obviously the immune system. But these calves can be assisted by cleaning the nostril, rolling calves onto their stomachs, which help to clear their lungs and assume normal respiration after the arduous birth; warming them using clean, dry towels to vigorously dry the hair (hair dryers can be another good option). Deep, clean, dry bedding is also recommended. Feeding calves, high-quality colostrum as soon as possible after birth, not only for the antibodies but because of the nutrients, hydration, and warmth to the stressed newborns, is probably the most important guideline.

Preventing Dystocia and Stillbirth

Efforts have been made to reduce the incidence of dystocia: selection for low calf birth weight, especially in heifers, selection for a larger pelvic area (height and width), discarding heifers with abnormally shaped or very small pelvic areas before breeding, reducing the incidence of twins increasing the progesterone concentration using CIDRs during the follicular phase before timed artificial insemination, are some of the examples.

Intensive monitoring of parturition is necessary to reduce the incidence of dystocia and stillbirth. The suggested intervals at which cows are monitored vary from 1 to 2 hours to 3 to 6 hours. Farmers rely on expected calving dates to manage cows around calving, and direct observations to identify calving cows. Automated monitoring of cow behavior has the potential to provide farmers with a more-accurate indicator of the day and time of calving when compared with the expected calving date.

It is necessary to record each birth and use the calving score (5 points) to set up a herd database that can be used to evaluate, not only breeding and calving management, but relating it to the subsequent performance of the growing heifers and the transition period of the dam.

The veterinary role is key in solving the very complex dystocia, but is it economically viable to call the vet to solve a leg turned back or head turned back in a dilatated cow? Does it not make more sense to train farm employees? Farmer employees’ obstetric skills and calving management training (recognizing problems and knowing when and how to assist) are associated with a reduction in dystocia rate and its effect on calf health.