By Kelly Froehlich

Vaccination against clostridium perfringens is universally recommended for small ruminants. Clostridium perfringens is a group of bacteria commonly infecting the intestine of small ruminants, causing a variety of illnesses often resulting in death. Although there are several bacterial types, clostridium perfringens C and D are of especial concern to small ruminants in North America. Type C most commonly affects lambs a few weeks old and rarely kids, while type D (a.k.a. overeating disease or pulpy kidney disease) occurs in sheep or goats of any age.

Clostridium is a natural resident in a small ruminant’s digestive tract and is also found in soil, feces, water and as a feed contaminate. Despite its common appearance, it remains relatively unharmful unless presented with opportunities to rapidly proliferate, causing a release of toxins. This generally occurs in animals that are under stress, causing a change in the intestinal environment. For example, younger animals transitioning to higher sugar, or starch feeds, can cause a proliferation in clostridium. Lambs nursing heavily lactating ewes or bottle lambs are at a higher risk for type C clostridium. Fortunately, preventing and mitigating effects of clostridium is easily done through a good clostridial vaccination program.

Clostridial Vaccines and Administration

There are several clostridial vaccines available; while generally inexpensive, price does increase per dose depending on if a 3-way, 7-way or 8-way toxoid vaccine is administered. These vaccines, known as bacterin-toxoids, are designed to provoke an immune response, while causing no harm to the animal. The 3-way vaccine called CD&T protects against Clostridium perfringens types C & D and Clostridium tetani. The 7-way and 8-way vaccines include additional protection from other clostridial strains, such as blackleg and malignant edema, which is considered less common for sheep in North America. For most operations, the 3-way provides adequate clostridium protection, but will be farm-dependent.

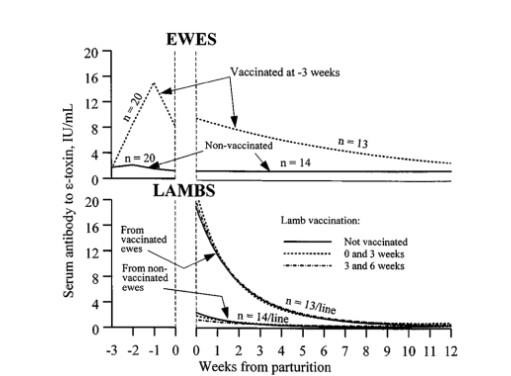

Clostridial vaccines should be given at least yearly to adult sheep previously vaccinated. Ideally it is given 3 to 4 weeks prior to lambing. This times peak antibody levels from the vaccine with colostrum production, providing immunity for the lamb or lambs. Prior to the first several weeks of age, lambs have an immature immune system in which vaccines may have little benefit (Figure 1). However, work completed at the U.S. Sheep Experiment Station has shown lambs born to unvaccinated ewes prior to lambing and given an injection at day 0 and 14 had an immune response at day 15. Given lambs' higher risk for clostridial issues, there may be benefit from vaccinating as early as 2 weeks of age to provide at least partial immunity.

Figure 1. Effect of vaccine schedule on blood concentration of the toxin epsilon (ε-toxin) caused by Clostridium perfringens type D in ewes and lambs

Figure 1 illustrates the effect of the vaccine schedule on blood concentration of the toxin epsilon (ε-toxin) caused by Clostridium perfringens type D in ewes (top panel) and lambs (bottom panel). Ewes vaccinated with Clostridium perfringens types C and D and Clostridium tetani (dotted line) had higher blood antibodies to ε-toxin than ewes un-vaccinated (solid line). Lambs from those same ewes were divided into 3 treatment groups: not vaccinated, vaccinated at 0 and 3 weeks, and vaccinated at 3 and 6 weeks of life. Lambs from vaccinated ewes had higher antibody levels than lambs from unvaccinated ewes; however, vaccinating the lambs did not increase antibody levels between the treatments. This suggests vaccinating young lambs provides no protection however, vaccinating ewes prior to lambing can impart immunity to the lamb. This work was conducted by de la Rosa et al. (1997) and published in the Journal of Animal Science, 75(9), 2328-2334.

In a disease outbreak, an anti-toxin could be provided for immediate short-term neutralization of formed toxins. Anti-toxins are different than the vaccine toxoids. In vaccines, toxoids are an inactivated bacteria toxin designed to stimulate the immune system to create anti-toxins or antibodies in the animal. Administered, anti-toxins provide toxin neutralization, but as the immune system did not create it, it will not create more, so only short-term immunity will be provided.

Naïve animals (never vaccinated) and lambs 2 weeks or older should be administered two doses of a clostridial vaccine according to label instruction under the advisement of a veterinarian. These two doses are vitally important in providing adequate antibodies and ensuring the immune system can recognize and handle potential clostridial issues. As always, good records and the 21-day slaughter withdrawal time should be considered when setting up a vaccine schedule.

Special Considerations for Goats

Goats metabolize vaccines and medicines differently than sheep. While most vaccine program recommendations are based off sheep, it is important to note there are physiological differences. For goats, Clostridium perfringens type D appears to be the most problematic, with Clostridium perfringens type C rarely being reported. Use of sheep-labeled clostridial vaccines in goats has shown variable protection. Administering a clostridial vaccine more than twice per year has been suggested for goats to receive adequate protection. This may be especially important for young, growing kids. It is important to talk with your veterinarian to determine an effective vaccine schedule for your goats.

Vaccine handling

Expiration dates and proper storage/handling are important to ensure efficacy. Vaccines, such as the CD&T, should be refrigerated to remain viable, including while vaccinating animals in the barn or pens. Refrigeration can be accomplished by placing bottles and syringes in a small cooler with ice to keep it chilled. Vaccines that have been warmed to room temperature, accidently left out or frozen can be assumed to be unviable and should be properly discarded. Clostridial vaccines typically recommend gently shaking the bottle before use. Most labels also indicate that the entire contents of the bottle should be used once opened, so choose a bottle size based on the number of doses needed. Leftover and expired products should be discarded to ensure the maximum efficacy.

Concluding Thoughts on Preventing Costridium Issues

- Naïve animals 2 weeks or older should be given at least 2 separate clostridial vaccines, followed by annual boosters.

- Follow label instructions or a veterinarian’s recommendations for a good clostridium vaccination program as part of a preventative herd/flock health plan.

- Follow label instructions on proper use and handling to ensure vaccine effectiveness.

- Follow label instructions for preslaughter withdrawal times and maintain complete records.

- Avoid sudden feed transitions to prevent drastic changes in the intestinal environment to minimize clostridium issues.

Source : sdstate.edu