By Michael Langemeier

Center for Commercial Agriculture

Purdue University

Obtaining control of land through leasing has a long history in the United States. Leases on agricultural land are strongly influenced by local custom and tradition. However, in most areas, landowners and operators can choose from several types of lease arrangements. With crop share arrangements, crop production and often government payments and crop insurance indemnity payments are shared between the landowner and operator. These arrangements also involve the sharing of at least a portion of crop expenses. Fixed cash rent arrangements, as the name implies, provide landowners with a fixed payment per year. Flexible cash lease arrangements provide a base cash rent plus a bonus which typically represents a share of gross revenue in excess of a certain base value. Each leasing arrangement has advantages and disadvantages. These advantages and disadvantages are discussed on the Ag Lease 101 web site (here). Rather than focusing on the advantages and disadvantages of various lease arrangements, this article uses a case farm in west central Indiana to illustrate net returns to land derived from crop share, fixed cash rent, and flexible cash lease arrangements.

Leasing Arrangements

Net return to land from 1996 to 2019 from a landowner perspective were computed for a case farm in west central Indiana. The case farm had 3000 crop acres and utilized a corn/soybean rotation. Lease arrangements examined included a crop share lease, a fixed cash rent lease, and a flexible cash lease.

With the crop share lease the landlord received 50 percent of all revenue (crop revenue, government payments, and crop insurance indemnity payments). In addition to providing the land, the landowner paid 50 percent of seed, fertilizer, and chemical (herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides) expenses as well as 50 percent of crop insurance premiums. The case farm participated in government programs (e.g., ARC-CO and PLC programs), and purchased 80 percent revenue protection coverage.

Fixed cash rents were obtained from the annual Purdue Farmland Value Survey. Specifically, cash rents for average productivity land in west central Indiana were used. The flexible cash lease arrangement used a base cash rent that was 90 percent of fixed cash rent. In addition to the base case rent, the landowner received a bonus of 50 percent of the revenue above non-land cost plus base cash rent if revenue exceeded non-land cost plus base cash rent. Revenue included crop revenue, government payments, and crop insurance indemnity payments. All cash and opportunity costs, except those for land, were included in the computation of non-land cost. More discussion regarding possible parameters that can be used for flexible cash leases can be found in Langemeier (2018).

Comparisons of Net Return to Land among Leasing Arrangements

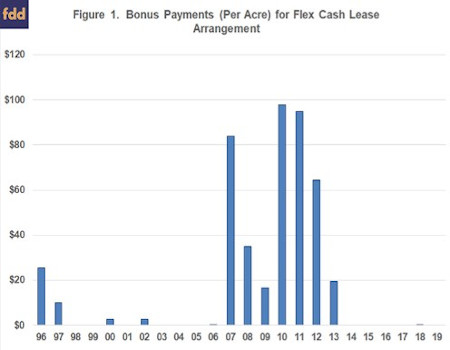

Before making comparisons between leases, we will briefly discuss bonus payments for the flexible cash lease. Per acre bonus payments for the flex cash lease arrangement are illustrated in Figure 1. Bonus payments were incurred in 13 out of 23 years from 1996 to 2019. Payments ranged from less than $1 per acre in 2006 and 2018 to $98 per acre in 2010. From 2007 to 2013, the average bonus payment was $59 per acre. Except for the small payment in 2018, the annual bonus payment since 2014 has been zero.

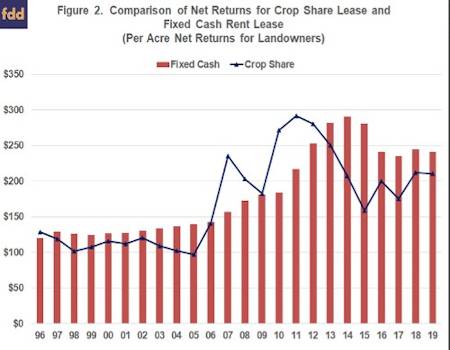

Pairwise comparisons were used to compare the three leasing arrangements. Figure 2 compares the crop share lease to the fixed cash rent lease. The landowner net return for the crop share lease was more variable. As would be expected, net return for the crop share lease increased faster when revenue was increasing, but also decreased more rapidly when revenue was declining. The net return for the crop share lease was higher than the net return for the fixed cash rent lease in 1996, and from 2007 to 2012. Since 2013, the net return for the crop share lease has been from $31 per acre (in 2013) to $122 per acre (in 2015) below the net return for the fixed cash rent lease. On average, from 2013 to 2019, the net return for the crop share lease was $57 per acre below the net return for the fixed cash rent lease.

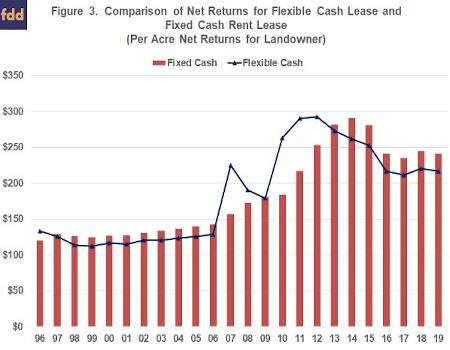

Figure 3 compares the net return for the flexible cash lease to the net return for the fixed cash rent lease. This graph looks remarkably similar to Figure 2. Net returns for the flexible cash lease were more volatile than the net returns for the fixed cash rent lease. The net return for the flexible cash lease was relatively higher in 1996, 2007-2008, and 2010-2012. During the 2007 to 2013 period, the average net return for the flexible cash lease was similar to the average net return for the share rent lease, and $38 per acre higher than the average net return for fixed cash rent lease. Since 2014, the annual net return for the flexible cash rent lease has been substantially below the net return for the fixed cash rent lease. On average, the net return for the flexible cash lease was $26 per acre below the net return for the fixed cash rent lease from 2014 to 2019. However, it is important to note that during this same period the net return for the flexible cash lease was $36 per acre higher than the net return for the crop share lease.

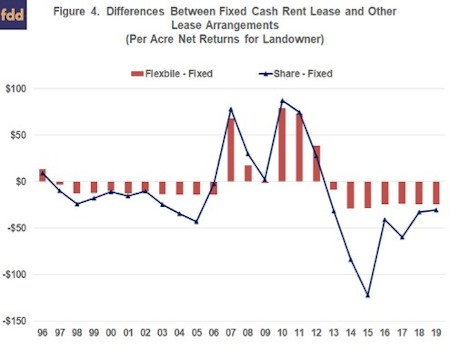

Differences between the fixed cash rent lease and the other two leasing arrangements are illustrated in Figure 4. This chart was created by subtracting fixed cash rent payments per acre from the net return for the flexible cash lease and the net return for the crop share lease. As was noted above, the net returns for the flexible cash lease mimic those for the crop share lease. However, there are a few differences in the trends for these two leases. The flexible cash lease did not increase as much as the crop share lease in 2007, 2008, and 2010. More importantly, from a downside risk perspective, the flexible cash lease did not decrease as rapidly as the crop share lease from 2013 to 2015.

Summary and Conclusions

This article used a case farm in west central Indiana to compare the net return to land for crop share, fixed cash rent, and flexible cash leases. The average net returns to land from a landowner perspective were similar among the three lease arrangements. The flexible cash lease mimicked the ups and downs of the crop share lease. However, the upward and downward spikes for the flexible cash lease were less pronounced than those for the crop share lease. Choosing among the leases depends on a landowner’s desire to capture improvements in crop share revenue and ability to withstand downside risk. The crop share and flexible cash leases allow landowners to more fully capture annual improvements in crop revenue, but also increase the probability of significant downward movements in annual net returns.

Source : illinois.edu