By Jonathan Coppess and A. Bryan Endres

Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics

University of Illinois

The preceding article discussed a lawsuit under the Clean Water Act that will be heard by the Supreme Court (farmdoc daily,

March 21, 2019). This article continues the discussion by reviewing a proposed rule published jointly by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers for defining the waters of the United States for purposes of the Clean Water Act; the proposed rule is open for public comment until April 15, 2019 (Office of the Federal Register,

February 14, 2019).

Background

As discussed previously, the Clean Water Act (CWA) was written and passed by Congress to restore and protect water quality and aquatic ecosystems throughout the county (farmdoc daily,

March 21, 2019). Since a plurality decision in 2006, a precise legal definition for navigable waters (waters of the U.S.), and the full scope of jurisdiction for the federal agencies, has eluded the courts and the federal agencies charged with the law’s enforcement. In the statute, Congress defined the term navigable waters as “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas” (

33 U.S.C. §1362(7)). In the conference report for the bill, the conferees instructed that they “fully intend[ed] that the term ‘navigable waters’ be given the broadest possible constitutional interpretation unencumbered by agency determinations which have been made or may be made for administrative purposes” (S. Rept. 92-1236, at 144).

Federal courts—including the Supreme Court—had generally agreed that the term navigable waters was comprehensive; it was to be interpreted so as to provide the lead federal agencies (the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers) extraordinarily broad authority and jurisdiction to protect water quality and aquatic ecosystems (United States v. Riverside Bayview Homes, Inc.; SWANCC v. United States Army Corps of Engineers). For example, the Court understood Congress had “intended to repudiate limits that had been placed on federal regulation by earlier water pollution control statutes and to exercise its powers under the Commerce Clause to regulate at least some waters that would not be deemed ‘navigable’ under the classical understanding of that term” (Riverside Bayview Homes, at 133). This changed with, and significant confusion and uncertainty were added by, the Supreme Court’s plurality opinion in 2006 (Rapanos v. United States). In 1985, a unanimous Supreme Court held that wetlands adjacent to navigable in fact waters (in this case a lake) are “inseparably bound up” with the adjacent waters and thus fall under the regulatory definition of “waters of the United States” (Riverside Bayview Homes). The Supreme Court revisited the waters of the United States issue again in 2001, where a closely-divided court in a 5 to 4 decision, held that “isolated” non-navigable ponds were outside the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act because there was not a significant nexus between the isolated ponds and any navigable waters (SWANCC).

It was the Supreme Court decision that followed five years later that created vast confusion; a plurality decision where only four justices agreed to limit the interpretation of the term waters of the United States as requiring a “relatively permanent” hydrologic connection to traditional navigable waters (Rapanos). In his opinion, Justice Scalia, writing for the four-justice plurality, noted the “Act does not forbid the ‘addition of any pollutant directly to navigable waters from any point source,’ but rather the ‘addition of any pollutant to navigable waters’” (Rapanos, at 743 (emphasis in original)). Accordingly, pollutants passing through conveyances or intermittent flows fall under the statute’s prohibitions. A fifth justice, Justice Kennedy, concurred with the plurality’s result, but for a different reason. Justice Kennedy returned to the “significant nexus” test of the SWANCC case, concluding that jurisdiction over wetlands and other non-navigable waters “depends upon the existence of a significant nexus between the wetlands in question and navigable waters in the traditional sense” (Rapanos, at 779). Moreover, the nexus must be assessed within the context of the Clean Water Act’s goal “to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters” (Rapanos, at 779). The four dissenting justices, in an opinion written by Justice Stevens, would have extended the definition of waters of the United States even further to include wetlands adjacent to tributaries of traditionally navigable waters (or non-isolated wetlands) (Rapanos, at 796).

Discussion

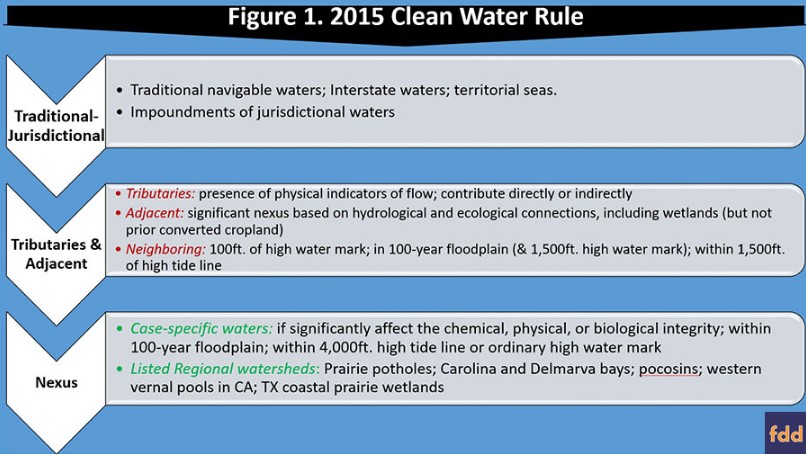

This uncertainty has led to attempted regulatory fixes. In 2015, EPA and the Corps of Engineers produced the Clean Water Rule, also known as Waters of the United States (WOTUS) that defined eight categories of jurisdictional waters under the CWA definition (EPA,

2015 Clean Water Rule). Adopting the significant nexus test from Justice Kennedy in the Rapanos case, the 2015 Clean Water Rule attempted to provide more clarity for non-navigable waters and non-adjacent wetlands. In addition to traditional jurisdictional waters (e.g., navigable and interstate waters, territorial seas), the 2015 Clean Water Rule also attempted to clarify jurisdiction over tributaries and adjacent waters, as well as neighboring waters. Finally, the rule described case-specific determinations of waters with a science-based significant nexus to traditional navigable waters. The 2015 Clean Water Rule also continued existing exclusions, such as for prior converted cropland, and would have specifically excluded from the definition of waters of the United States all groundwater, including groundwater drained through subsurface drainage systems. Figure 1 summarizes the 2015 Clean Water Rule.

The 2015 Clean Water Rule was attacked in court immediately; thirty-one states and 53 non-state groups sued after it was published. In August of 2015, the federal district court for the District of North Dakota blocked the rule from going into effect in the thirteen states that had challenged the rule before it (North Dakota v. EPA). Upon appeal, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily stopped the rule nationwide (In re EPA & Dept. of Def. Final Rule).

Soon after taking office, President Trump issued an executive order that directed the agencies to review the 2015 Clean Water Rule and to consider revising it to align the interpretation with Justice Scalia’s plurality opinion definition in Rapanos (

Executive Order 13778). EPA and the Corps of Engineers published a proposed rule to revise the definition of “waters of the United States,” on February 14, 2019 (

Proposed Rule). The comment period for the proposed rule closes on April 15, 2019.

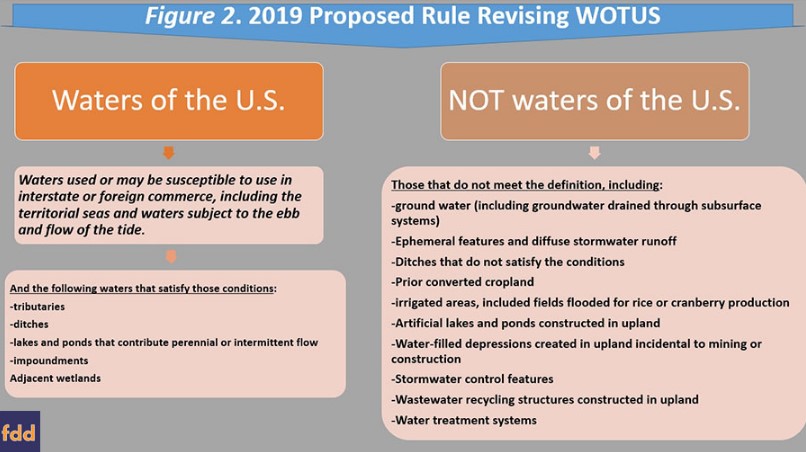

In short, the new rule proposes to distinguish more clearly between water subject to federal jurisdiction under the CWA and waters that are exclusively the jurisdiction of State and Tribal governments. EPA and the Corps of Engineers propose that “waters of the United States” encompass only those waters that are currently used for interstate or foreign commerce, and those waters that have been so used in the past or that may be susceptible to such use. This includes the territorial seas and any waters that are subjected to the ebb and flow of the tide; together this constitutes the base definition for waters of the U.S. and all other types of water are defined in relation to them. The definition also includes tributaries, ditches, lands and ponds, impoundments and adjacent wetlands but all have to be connected to the base definition for waters of the U.S., such as by contributing perennial or intermittent flow.

The rule also proposes to exclude certain waters from the definition of “waters of the United States.” In general, all waters or water features that are not identified under the base definition are not waters of the United States. Groundwater, including groundwater drained through subsurface drainage, is again specifically not included. Likewise ephemeral features and diffuse stormwater run-off, other ditches not previously identified, prior converted cropland, artificially irrigated areas (including rice and cranberry fields), artificial lakes and ponds, as well as water-filled depressions are excluded. Finally, stormwater controls and wastewater recycling structures, along with waste treatment systems, are not included. Figure 2 summarizes the 2019 proposed rule for the revised definition.

Of note for agriculture, the new definition continues the exclusion from jurisdiction of prior converted cropland, just as the 2015 Clean Water Rule had. The agencies note that the term is being moved into this definition to help clarify that once prior converted wetland has been abandoned (not used at least once in five years; use includes fallow for conservation purposes) and returns to wetlands, it is no longer excluded from jurisdiction. Acreage enrolled in a USDA conservation program would not be considered abandoned and thus would maintain its status as prior converted cropland.

Concluding Thoughts

The agencies contend that the proposed rule is “superior” to previous rules and that it is intended to resolve the longstanding confusion surrounding federal jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act. The agencies also contend that the proposed rule better aligns with the text of the statute, legislative history and the limits of Congress’s authority, as well as Supreme Court precedent. Whether this proposed rule, if it becomes final, accomplishes these goals will await the litigation that is certain to follow it. What is most clear, however, is that the main purpose underlying this rule is that of designing a new definition for “waters of the United States” that scales back the scope of the statute and best aligns with Justice Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos v. United States. Aside from the specific terms for waters in the proposed definitional revisions, this goal raises significant Constitutional questions that include the separation of powers doctrine. Not only did Justice Scalia’s 2005 plurality opinion divert from long-established precedent, it also failed to garner a majority of justices on the Supreme Court. Despite those shortcomings, the new rule seeks to revise the agencies’ interpretation of the Congressional definition to implement a rather controversial interpretation of the statute. Under Article I of the United States Constitution, it is Congress that is granted the legislative power of the federal government—including amending statutes—but Congress has not revised its definition in the statute. Arguably, this could be the most important issue in any subsequent litigation given the implications for such fundamental constitutional matters.