By Robert Klein and Cody Creech

Did you know you can lose two wheat crops from one hailstorm? It could be yours or your neighbor’s.

The first loss is the current wheat crop being hailed. The second loss is from the disease Wheat Streak Mosaic. For example: The volunteer wheat from one neighbor's hailed winter wheat crop served as a host for the virus vector and the farmer’s wheat crop across the road averaged just five to six bushels per acre on 320 acres. His other fields not affected by Wheat Streak Mosaic averaged 60 bu/ac.

Volunteer wheat can provide the summer "green bridge" for the disease wheat streak mosaic and other virus diseases. By far, the greatest risk of losses from mite-transmitted viruses occurs when there is a summer "green bridge" of volunteer wheat emerging before harvest. This almost always occurs as a result of wheat seed shattered from heads during hailstorms.

The damage can be as great as a total loss of the field affected by wheat streak mosaic virus (Figure 2). One tenant even had a greater loss because the landlord thought there had to be enough wheat in the field to pay for harvest, but the field only averaged six bushels per acre which was not enough to cover the cost of custom harvest.

Figure 2. Volunteer wheat, like that illustrated in the inset image, resulting from a widespread hail event that occurred prior to harvest in 2016 resulted in widespread yield loss to mite-transmitted viruses in Deuel and Garden counties in 2017.

The mites (Figure 3) and viruses survive and build up through the summer on this "green bridge," then in the fall, the mites move from volunteer wheat to newly emerged winter wheat plants, transmitting the viruses. Mites can transmit wheat streak mosaic virus, High Plains wheat mosaic virus, and Triticum mosaic virus, creating the likelihood of severe mixtures of viral infections.

Mites depend on wind for dispersal. Through the fall, as mite populations increase, they leave the protected areas of volunteer wheat plants (rolled leaves and whorls) and crawl to leaf tips or other exposed areas where they become airborne. After landing on a new host, the mites crawl to the youngest leaf and begin to feed and reproduce.

Figure 3. Wheat curl mite on a wheat leaf.

In heavily infested volunteer wheat, most mites will carry the virus. Transmission to the young winter wheat plants requires only a few viruliferous individuals. Immature mites acquire the virus in as little as 15 minutes as they feed on infected leaves. Mites remain active for most of their lives (two to four weeks or longer with cool temperatures), but the transmission efficiency of adult mites decreases with age.

Research has found that mites can only survive off green plants a day or so under hot temperatures, but two to four days under lower temperatures. Thus, a significant number of mites may be transported by the wind from greater distances than we originally thought; however, the greatest risk is to the fields closest to the volunteer wheat. Video 1 demonstrates mite and virus development throughout the year.

Volunteer wheat is not the only host for the wheat curl mite (Figure 3). Over-summering hosts can also include corn or foxtail millet. An important consideration for these crops is to try to minimize the overlap of the green and growing summer crop and the emerged new crop of wheat. The greater the overlap the greater the risk from these hosts.

Some summer annual grassy weeds can also act as mite and virus hosts — the greater the density of these grasses, the greater the risk. Recent research has evaluated the suitability of weedy grasses as hosts for both the curl mite and the wheat streak mosaic virus. Barnyardgrass topped the list in terms of suitability for both virus and mites, but fortunately it is not a common grass in wheat except in low areas — including terraces — that accumulate water.

In contrast, green foxtail is a rather poor host for the mites but could be an important disease reservoir simply because of its abundance. In one example, the source of a winter wheat field infected with wheat streak mosaic virus was a grain sorghum field with grassy weeds adjacent to the winter wheat field. Take note of significant stands of these grasses and control them as you would volunteer wheat.

Timely Weed Control Helps Manage Yield Loss Risk

Risks from not controlling volunteer wheat and weeds include:

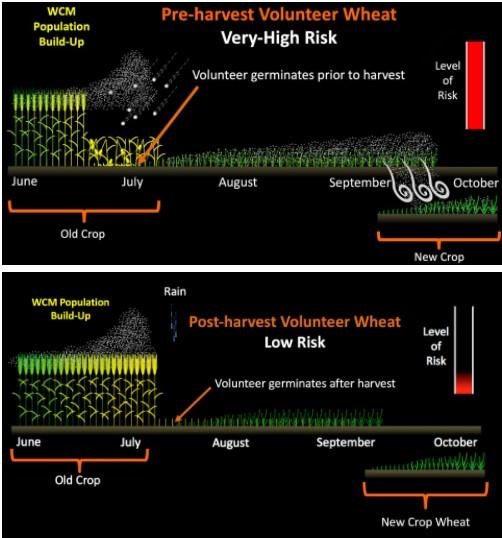

- Pre-harvest volunteer wheat can cost you or your neighbor the value of next year's winter wheat crop due to loss from wheat viruses. In addition, loss of the winter wheat residue can lead to much lower yields in the following corn or grain sorghum crop. While control of both pre- and post-harvest “green bridge” hosts is important, timely control of pre-harvest volunteer wheat will have a greater impact on ultimately reducing virus transmission and yield loss (Figure 3).

- Any volunteer wheat that has emerged around wheat harvest, even in a summer crop like sunflower or corn, can also be a significant risk. Figure 4 shows considerable volunteer wheat in a sunflower field in the fall that was heavily infested with mites. This field resulted in total loss to adjoining wheat fields.

- Uncontrolled volunteer wheat and weeds can cost you 30 bu/acre or more of corn or sorghum the next year due to soil moisture taken up by volunteer wheat and weeds.

- Weed control may be more difficult and expensive in next year's crop.

- Planting the next crop may be more difficult in last year's weed-infested stubble.

Figure 4. Comparison of the increased disease risk of pre-harvest volunteer wheat (above, usually from hail storms) versus post-harvest volunteer wheat (below) in the development of wheat streak mosaic.

Impact of Wheat Seeding Time

The earlier winter wheat is seeded and the longer mild weather extends through the fall, the greater the risk of spreading wheat streak mosaic and other viral infections. For instance, near Ogallala, the winter wheat yield doubled with a one-week delay in seeding date. Under warm fall conditions, the probability of secondary spread of mites and viruses increases, resulting in greater incidence of infection.

In another field near Ogallala, wheat seeded on Sept. 8 was lost to the wheat streak mosaic virus while a field across the road seeded Sept. 19 to the same winter wheat variety was not affected by the virus.

Reproduction and spread of mites stop with cool temperatures in the fall; however, mites can survive cold winter temperatures. The virus survives the winter within the plant, and the mites survive as eggs, nymphs or adults protected in the crown of the wheat plant. As winter wheat greens up in the spring, mites become active and the virus may be spread to healthy winter wheat plants or to emerging spring wheat, although this is much less of a threat than fall transmission.

Figure 5. Uncontrolled volunteer wheat in a sunflower field played host to a heavy mite infestation in the fall, which led to total loss of the adjoining neighbors' wheat fields the next year.

Additional Losses Associated with Volunteer Wheat

Diseases. Volunteer wheat can provide habitat for many other pathogens that may later be a problem if continuous wheat is seeded in the fall. Root rots as well as seedling blights caused by Fusarium species are specific examples. Occasionally, fall season leaf rust or stripe rust can occur. Severity of these rust diseases on the newly emerged winter wheat crop will be much higher if volunteer wheat, which serves as a local source of inoculum, is not controlled.

Aphids. Volunteer wheat also attracts the Russian wheat aphid and other cereal aphids. If allowed to remain until the new wheat crop emerges, the risk of aphid infestation and barley yellow dwarf increases. This could be particularly important this year as fields with damaging populations of Russian wheat aphid were reported in Kimball County this year. If volunteer wheat is allowed to persist in these fields, we could see significant risk of aphid infestation in the 2022 cropping season.

Hessian Flies. Volunteer wheat allowed to survive through late summer and fall also dramatically increases the risk from Hessian fly.

Moisture Loss. Volunteer winter wheat and weeds also use soil water, which would otherwise be used by the following crop. The average soil water loss due to volunteer wheat is three inches, which can result in yield losses of 30 bushels or more in corn or sorghum. Occasionally the loss can be as much as 100 bushels. How does this happen when we only save three inches of soil water? With the additional three inches of soil water, the corn or sorghum crop will survive up to three weeks longer without rain before being lost to drought. Hence, if enough rain is received in time, we have observed yields of 100 bushels or more of corn or sorghum where volunteer wheat and other weeds were controlled after wheat harvest.

Increased Weed Seed. Letting weeds produce seed increases the weed seed bank and makes weed control more difficult in the succeeding crops. The additional weed residue also makes planting more difficult in the following crop.

Summary

Volunteer wheat surviving through the summer and fall creates numerous risks for the subsequent wheat crop as well as other rotated crops. Controlling volunteer wheat will reduce the risks from these threats and ultimately improve the bottom line.

Source : unl.edu