Drought stress is the most important factor explaining year-to-year variation in crop yields in our environment. It is not uncommon to see 50% yield reductions due to drought stress. Soils differ in their sensitivity to drought, while there are several management practices that can help reduce your vulnerability, which we will review here:

1. Drought vulnerability varies by soil type

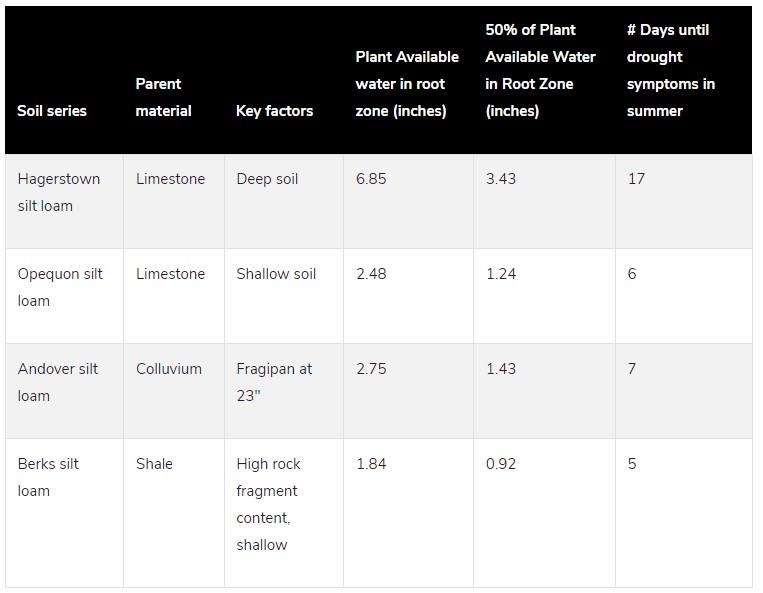

Plant available water (PAW), which is the water the soil is able to hold between permanent wilting point and field capacity, varies tremendously between common soil types in our state. Using soil characterization data, we calculated the PAW in the rootable zone of four common agricultural soils in Pennsylvania (Table 1).

Table 1. Plant available water (PAW) in the root zone of four soil series commonly used in Pennsylvania and how that affects number of days until drought symptoms appear after a soaking rain.

The Hagerstown is a typical deep limestone soil. We assumed roots would grow to 50" depth. The Opequon is a soil that is typical of rock outcroppings in limestone country – in this case, depth to bedrock was only 17", greatly restricting rooting depth. The Andover soil has a shallow fragipan at 23", a dense soil layer that also limits rooting depth and water percolation. These soils are poorly drained because of a seasonally high water table. However, in the summer crops grown on these soils tend to suffer from drought due to shallow rooting. Andover soils are common on the sides of the mountains in the Ridge and Valley Region, and can also be found in western and northern Pennsylvania. Berks soils are well-drained soils developed from shale. They are very droughty because of high rock fragment content. Typically, crops will start showing drought symptoms when PAW is 50% depleted. Assuming 1.4 inches of water use per week (typical of a corn crop in July), the stark differences between soils now become evident. On a deep limestone soil it may take 17 days of no precipitation before drought symptoms appear while on the other soils it takes less than a week! Key message is that especially on the droughty soils it becomes crucial to use drought-mitigating strategies.

2. Mitigate drought risk by increasing crop diversity

Drought risk can be reduced by growing a diversity of crops on the farm. The peak of moisture demand of corn (about 1.4 in/wk) is in July and early August when it needs about 1.4 inches per week, while that of small grains like wheat (about 1.7 in/wk) is in June. Because temperatures tend to be higher in July/August, drought risk is greater in corn than in small grains. Further, corn is highly sensitive to drought at silking increasing yield reduction risks due to drought. Therefore, you decrease drought risk by growing small grains. Growing corn after deep-rooted crops like alfalfa results in deeper rooted corn also – this is one of the main reasons for higher corn yields in rotations with perennial forages. Finally, some farmers have stopped growing corn on droughty soils and moved to more drought resistant crops like forage sorghum or sorghum-sudangrass.

3. Mitigate drought risk by planting early

It is crucial to develop a deep root system before summer droughts hit your farm. Late planted corn or soybeans is much more sensitive to drought than early planted crops because of a smaller root system at the beginning of July.

4. Mitigate drought risk by growing cover crops instead of double-cropped soybeans

In a study comparing grazing of cover crops after small grains we found that grazing cover crops can be more profitable than double-cropped soybeans, especially on drought soils where double-cropped soybeans often fail. Similarly, short-lived annuals such as rye or triticale can be harvested for silage which can be more profitable on droughty soils than double-cropped soybeans.

5. Reduce drought risk with heavy mulch cover

Crusting and sealing are common phenomena on exposed soil, and runoff can be greatly reduced by keeping soil covered with crop residue. On top of that, the residue conserves moisture by reducing water evaporation from the soil surface. In a study in Eastern Ohio, 16% of annual precipitation was lost due to runoff in conventional tillage, while it was virtually nil in continuous no-till that had high crop residue cover. In a study in Kentucky, moisture evaporation loss was 2.5 inches per month until canopy closure in conventional tillage, while it was only about 0.3 inches in no-till due to heavy mulch cover.

6. Reduce drought risk by improving soil health

Roots don’t develop well when soil is compacted, increasing drought risk. It becomes therefore very important to avoid soil compaction. Further, soil water storage capacity can be increased by improving the soil organic matter content. The USDA-NRCS estimates that with every 1% increase in organic matter in the topsoil, soil moisture storage capacity increases 20,000 gallons per acre. Soil organic matter content can be increased by using no-tillage, using manure or compost instead of chemical fertilizer, and leaving crop residue in the field. Cover crops are also an important tool to improve soil health. Finally, build soil health by stimulating biological activity in soils. One example is the deep burrowing earthworms that are favored by leaving crop residue cover and avoiding soil tillage, which also stimulates microbial activity. Together soil health improving practices help improve the water holding capacity of the soil and improve porosity so water can easily infiltrate and percolate to deeper layers. The residue helps reduce runoff and evaporation.

In summary, drought risk varies by soil type. On droughty soils it is extra important to use drought mitigation measures, although in extreme years like 2023 it also makes a difference on soils with high moisture storage capacity. Farmers can decrease drought risk by increasing crop diversity, use no-tillage with heavy mulch cover, and improve soil health by reducing soil compaction, improving soil structure and increasing soil organic matter content.

Source : psu.edu