Management adjustments are needed when harvest maturity is not ideal.

Extreme weather and delayed planting make it certain that some fields planted for corn silage will not have time to reach optimum maturity this year before frost brings an end to the growing season. Michigan State University Extension has collated information from across the northern Corn Belt to assist producers with management guidelines for ensiling immature and frosted corn in this year of extremes.

The greatest challenge of harvesting immature and possibly frosted corn for silage is that it is very likely to be too wet for ensiling. Target moisture at ensiling in bunkers and piles is 65-70% while corn ensiled in upright silos should be a little dryer at 60-65% moisture. More than 70% moisture leads to clostridial fermentation and excessive effluent loss, resulting in increased dry matter shrink, reduced nutritive value, reduced dry matter intake by cows and economic loss. Silo effluent is also a regulatory issue because it cannot be allowed to contaminate surface water.

Harvest timing and silage quality

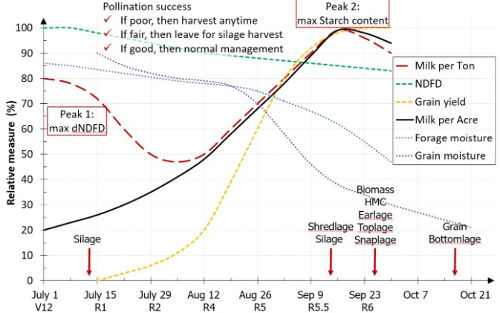

Corn is a grass and exhibits the same trade-off between dry matter yield and forage quality in the early growth stages as other grasses. Corn is unique among forages in that the developing grain allows an increase in nutritive value to compensate for the decline in fiber digestibility (NDFD) as plants mature. University of Wisconsin research shows that milk per ton of corn silage declines from prior to flowering until R3 (milk) growth stage before recovering and peaking at R5.5 (half milkline), while milk per acre continues to increase throughout this period (see figure).

Milk production per ton of forage may be 46-63% lower at milk stage versus earlier or later stages. Therefore, if weather projections indicate corn will not be able to achieve R5 or greater before cold weather stops growth and best forage quality is the main objective, it may be better to harvest before R1. This immature corn also has greater sugar content and crude protein and more digestible cell wall than normal corn silage.

It takes corn about 900 growing degree days (GDD) after silking to reach silage maturity. When planted at the normal time of year, this takes about 45 days. When planted later, it takes longer to accumulate 900 GDD after silking because growth is pushed into a cooler time of year, and development slows down to require 55 to 70 days to silage maturity. Therefore, corn planted in mid-July or later has little chance of reaching maturity before frost in Michigan. If silking date was noted, the probability of reaching silage harvest before frost for a specific location can be determined using

the recently updated estimates for Michigan fall frost dates.

Corn may withstand temperatures of 32 degrees Fahrenheit for up to four hours with minimal damage, but only a few minutes below 28 F. Be aware that frost damage can vary across a field due to differences in topography and exposure. Frozen tissue will quickly turn dry and brown. Be careful! Recently frosted immature corn can still be too wet to ensile even if the leaves seem completely dry because most of the moisture is in the stalk.

Do not be too quick to harvest just because a frost occurred. Frost is less damaging to yield and quality the closer the corn gets to physiological maturity, and frosted plants may continue to mature grain. Leaving frosted corn silage in the field too long risks shatter and loss of leaves, but leaves are only about 15% of the total dry matter yield. If the stalk or any leaves above the ear are still alive, ears continue to convert sugar to starch after frost and advance towards black layer maturity.

To tell if the stalk is still alive, look for green color on the stalk itself, the bases of the leaves, and the husk. Corn whole plant moisture drops by about 0.5 percentage points per day during grain fill and this dry-down rate does not change after frost. Corn is usually near the ideal moisture for silage when kernels reach half milkline, but there is no substitute for actually measuring moisture in a sample of chopped silage using a Koster moisture tester or microwave.

Many delayed planting corn fields have lots of variability in maturity across the field. Be aware of these areas when harvesting and harvest sections separately if possible. If silage must be harvested above desired moisture, adding a source of dry matter as the silo is packed can help improve fermentation. Dry matter sources that include straw, hay or grain. Silage moisture will be reduced by 1% for every 30 pounds of dry matter added per ton of fresh silage. When corn is immature and kernels are still soft, silage can be chopped more coarsely than usual to help improve ruminally effective fiber, and grain processing is not a critical need.

Frost can damage corn kernels and anything that damages kernels can allow fungi to get access to the plant. This may increase mold formation and the possibility of mycotoxins, especially if corn stands in the field for a long time before chopping. If corn gets too dry before chopping, mold formation can continue in the silo. If molds and mycotoxins are a concern in a particular field, please submit a silage sample to MSU. Frost and cool weather (daytime highs less than 55-60 F) in general may reduce the number of beneficial lactic acid bacteria on the plants, so applying a commercial lactobacillus inoculant can be good insurance for a vigorous fermentation.

Frosted corn silage may accumulate nitrate if the stalk and some leaf material is still alive. To reduce this risk, cut stubble higher than normal at 18 inches. This reduces yield but increases overall forage quality because the lowest part of corn stalk is wetter and of poor quality (low NDFD). By raising cutting height to 18 inches, forage moisture decrease by 3-4%, forage yield decreases 10-15% but forage quality increases 8-12%, so overall yield (milk per acre) is only reduced by 3-4%. For more information from MSU Extension on nitrate toxicity, see “

Make a plan for drought-stressed corn silage in 2018.”

Harvesting and feeding immature corn immediately as green chop may be a solution for some situations. If feeding as green chop, be very aware of nitrate risk.

Corn can be harvested like other large forage grasses such as forage sorghum. The appeal of this system is that immature, wet corn can be cut and allowed to wilt before being chopped. This system works best with corn prior to flowering and allows producers not interested in grain content, such as grass-fed beef producers, to take advantage of the high vegetative yield potential of corn. Some grass-fed beef producers in Michigan report success with growing corn at high densities (less than 45,000 plants per acre) in 15-inch rows, cutting with a sickle bar mower before R1, and baling and wrapping using a large round baler with knives.

We evaluated whether immature corn grown at normal population and row spacing could also be windrowed and picked up with a forage chopper after wilting. We tested this idea with R3 corn and discovered that cutting corn with hay equipment is challenging when ears are present. A discbine and a sickle-bar haybine stripped the ears off the stalks and threw them out of the windrow where a forage pickup head would miss them. Best mowing results were obtained with a disk mower with the front guides raised and blades angled up. Mowing at normal hay-cutting height over a rough corn field added a lot of dirt to the forage. Corn stalks did not form a tidy windrow and may be difficult to pick up cleanly with a forage chopper, leading to more dirt in the forage. Dirt in a silo is extremely undesirable because dirt contains clostridial bacteria which may dominate the fermentation. This method will require careful tweaking of equipment settings to be successful and is probably best suited for very immature corn that has not silked yet.