By Jonathan Coppess

Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics

University of Illinois

Each fiscal year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Farm Service Agency (FSA) provides an important source of credit to farmers who are unable to borrow from commercial sources. The farm loan programs provide direct credit and guarantees loans made by private lenders. Like much of farm policy, the farm loan programs are rooted in the New Deal but also carry a troubled legacy of discrimination and disparate treatment (Carpenter 2012; Milligan 2016; Nickerson 2018; Pigford v. Glickman, 185 F.R.D. 82 (D.D.C. 1999)). This article begins a series reviewing the history and development of the farm loan programs.

Background

FSA’s farm loan programs include direct and guaranteed farm ownership loans, as well as direct and guaranteed farm operating loans. The programs are normally reauthorized in Title V (Credit) of farm bills and limited to those who meet a series of eligibility standards. For example, a farmer or rancher is eligible for a direct farm ownership (real estate) if they can demonstrate at least 3 years of acceptable experience (including education or training) and are “unable to obtain sufficient credit elsewhere to finance their actual needs at reasonable rates and terms” (

7 U.S.C. §1922 et seq.). Among other things, the 2018 farm bill increased the loan limits for farm ownership loans to $600,000 and $1.75 million for a guaranteed loan (

7 U.S.C. §1925) and increased the lending limits for farm operating loans to $400,000 for direct loans and $1.75 million for guaranteed (

7 U.S.C. §1943). The portfolio also includes emergency loans, youth loans and conservation loans, as well as assistance for beginning farmers and ranchers and minority and women farmers and ranchers.

The farm bill authorizes appropriations for direct and guaranteed lending through the Agricultural Credit Insurance Fund (ACIF) up to $10 billion per fiscal year (

7 U.S.C. §1994). FSA provides loans and guarantees from the funds in the ACIF at low interest rates, converting the appropriated funds into loans and loan guarantees. Total FSA lending exceeded $5 billion in each of fiscal years 2018 and 2019 (USDA, FSA

Farm Loan Programs). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the farm loan programs as reported by FSA for fiscal years 2018 and 2019.

The farm loan program authorities are contained in the Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act (ConAct), previously the Consolidated Farmers Home Administration Act of 1961 which was Title III of the Agricultural Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-128). Like most of today’s farm policy, the farm loan programs trace their origins to the New Deal. The following discussion reviews the origins of the direct credit programs as developed in the 1930s.

Discussion

Today’s farm loan programs originated with the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act of 1937, signed into law by President Roosevelt on July 22, 1937 (P.L. 75-210). The 1937 Act provided loans to enable persons to acquire farms but only “farm tenants, farm laborers, sharecroppers” and others who received most of the income from farming were eligible. Critically, preference for loans was provided to married people and those with dependent families, as well as those who owned livestock or farm equipment “necessary successfully to carry on farming operations” (P.L. 75-210, at Sec. 1). The program limited loans for farm purchases to only those farms that were determined “sufficient to constitute an efficient farm-management unit and to enable a diligent farm family to carry on successful farming” based on the locality of the farm (P.L. 75-210, at Sec. 1). The Secretary was to appoint a county committee of three farmers who lived in the county and they were given authority to examine applications, appraise farms and certify to the Secretary that an applicant was eligible for a loan “by reason of his character, ability, and experience” demonstrating a likelihood to succeed in farming and repay the loan (P.L. 75-210, at Sec. 2). Congress also provided authority to USDA for what were called rehabilitation loans, which would be used to purchase livestock, equipment and other supplies for a farm (P.L. 75-210, at Title II).

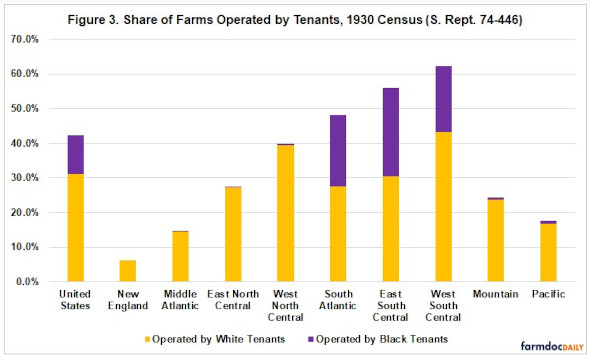

The impetus for the 1937 Act were concerns about the increasing prevalence of farm tenancy during the Depression. The Senate took the first steps in 1935, passing a bill to “deal with, in a broad way, the farm tenancy problem of the United States” for which the “evils inhering” were “manifest and manifold” (S. Rept. 74-446). Among these evils were poverty, the frequency with which tenant farmers and their families moved, the insecurity for these farm families, and the impacts on communities, but also included the millions of acres owned by “absentee owners” for which there was a failure to “give proper attention to the preservation of the soil and improvements on the farm “ (Id.). The Senate bill sought to “promote more secure occupancy of farms and farm homes” and “to correct the economic instability resulting from some present forms of farm tenancy” (S. Rept. 74-446). The committee reported included data from the 1930 census that reported 2,664,365 farms operated by tenants (42.4%) out of 6,288,648 total farms. Figure 3 illustrates the regional breakdown from the 1930 census included in the committee report.

Senator John Bankhead (D-AL) led the Senate Agriculture and Forestry Committee’s efforts on the bill. As initially designed, it would have established a federal Farmers’ Home Corporation with $50 million in capital stock and authority to issue up to $1 billion in bonds on the U.S. Treasury; funds were to be used to make loans for small farms and farm homes. Most notably, the Senate bill also included authority for the Corporation to purchase or otherwise acquire real property that could then be resold or leased (S. Rept. 74-603). Eligibility was limited to “farm tenants, share-croppers, farm laborers, or those who recently were farmers” with preference for those who were married or had dependent families; loans were not to be made to anyone found to have sufficient income from farm property (S. Rept. 74-446; 74-603). The bill was subject to extensive debate on the Senate floor and was sent back to the committee for revision, but much of the this was due to dilatory tactics by Southern Senators fighting against anti-lynching legislation (Baldwin 1968). The Senate finally passed Bankhead’s bill in late June, but it went no further in the 74th Congress. The Senate bill died in Chairman Marvin Jones’ (D-TX) House Agriculture Committee, in part because Chairman Jones had a different policy for the farm tenant problem (Baldwin 1968; Maddox 1937). The effort was further derailed when the conservative majority on the Supreme Court struck down the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act in January 1936, and Congress quickly responded with the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act of 1936 (

farmdoc daily,

September 25, 2020;

November 7, 2019).

After winning a landslide reelection and increasing Democratic majorities in Congress in 1936, President Roosevelt and Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace turned their attention back to the farm tenancy issue, quickly establishing a Special Committee on Farm Tenancy. The President reported its findings to Congress in February 1937, which included concerns about the trend of decreased farm ownership and increased tenancy—estimated an additional 40,000 tenants per year, pushing them to above 40 percent of all farmers. The report also discussed the consequences of farm tenancy for farm and rural security, health and well-being, as well as the implications for care of soil and natural resources (H. Doc. 75-149). Among the Special Committee’s recommendations was the creation of a Farm Security Administration within USDA that would undertake the purchase of lands which it would then resell to tenants, sharecroppers and farm laborers through long-term contracts.

The ability for a federal agency to purchase and resell farmland was a key sticking point in the House Agriculture Committee; in 1937, a program for federal purchase and resale of farmland was rejected during markup before the bill could be reported (Baldwin 1968; Maddox 1937). After the House passed its bill, the Senate again considered and passed its bill which included authority to purchase farmland and resell the land to tenants under contract after a trial leasing period. This provision for a land purchase and resale program lost to House opposition in conference; the final bill provided for low-interest loans to purchase farms and farm homes, as well as rehabilitation loans to improve farms or purchase supplies, livestock and equipment. Importantly, the loans were operated through an appointed county committee of local farmers. USDA quickly put the programs in place, converting the Resettlement Administration into the Farm Security Administration to implement and administer the programs.

The Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act was notable and controversial at the time but has been less prominent historically than its New Deal brethren. The 1937 Act provides an important piece of the overall farm assistance puzzle during its critical founding era. It sat at the intersection of some of the most troubling and systemic issues faced by policymakers, connecting the Great Depression’s impacts on farmers and rural America, but also those of the Dust Bowl as it decimated the southern Great Plains (Phillips 2007). For example, Title III authorized a limited program of “land conservation and land utilization” that included the “retirement of lands which are submarginal or not primarily suitable for cultivation” (P.L. 75-201, at Title III; Maddox 1937). It was part of the larger response to the Dust Bowl, and constitutes an early development for conservation policy (Hurt 1985; Hurt 1986;

farmdoc daily,

October 24, 2019). The most unique feature of the Act, however, was its most telling; focused on helping tenants, sharecroppers and laborers purchase farms of their own, the policy mixed progressive rural and land reforms with the consequences of acreage policies enacted as part of the adjustment program—a clear window into a troubled time.

To supporters, the 1937 Act was significant progress towards helping some farmers get established on their own farms and researchers found real benefits from the bill; those who were able to receive loans and the assistance for rural rehabilitation were found to have been helped considerably and that the policies made a difference on the ground, albeit limited (Baldwin 1968). Supporters of more progressive and far-reaching policies, however, considered the final product “nothing more than an ordinary farm mortgage program on very liberal terms” but intentionally limited to only the “highest type of tenant” (Maddox 1937, at 449). From using local committees to the inability for USDA to purchase land for resale, critics understood that the loans were unlikely to help “the very low income classes who are most in need,” especially in the “plantation areas of the South” (Id., at 451-52) and that Congress did not enact a program “conducive to the promotion of ownership among persons of low economic status” that would have benefited “the lower classes of tenants, sharecroppers, and laborers . . . the ordinary southern sharecropper and laborer” (Id., at 453-54). Senator Bankhead, in particular, was an inauspicious leader for the effort given his pedigree, connection to cotton planters and views on race and segregation; his efforts understood to be more class-based and populist, seeking to help white tenants and sharecroppers modestly rise above the state in which the Depression had left them (Olsson 2015; Baldwin 1968).

These criticisms of the 1937 Act are particularly notable in historical context. The New Deal acreage programs had a disparate impact on the tenants and sharecroppers in the South because cotton planters reduced the acres they farmed while refusing to share the federal payments. Federal assistance was instead used by the planters to consolidate land holdings, purchase tractors and other equipment, as well as diversify into other commercial crops. Not surprisingly, it was an effort that fell hardest on Black tenants and sharecroppers during the Jim Crow era and the Great Depression. This displacement received national attention at the time due to the formation of the biracial Southern Tenant Farmers Union in 1934, a subsequent strike by cotton pickers and violent retaliation by cotton planters and their allies in white supremacy. The consequences of the acreage programs were also the source of internal power struggles within USDA that resulted in a purge of liberal appointees by cotton allies in the Department; all of which either preceded or coincided with development of the 1937 Act and inform our understanding of its origins, as well as the discrimination it would further (Conrad 1965; Baldwin 1968; Daniel 1985; Cobb 1992; Olsson 2015).

Conclusion

Farm loan programs present another paradox in farm policy. The loans remain an important source of credit for many farmers who struggle to get loans from commercial sources, especially young and beginning farmers. At the same time, the loan programs have been the primary source of discrimination and disparate treatment by USDA. These contradictions were designed into the policy from the start and reinforced in its early years, but did not protect against being viewed “as a disturber of the southern way of life” in the Jim Crow era (Baldwin 1968, at 286). The history and development of farm loan programs provide a stark, troubling reminder how benefits of policy can be overshadowed; when used to take land from some farmers or drive them out of farming, policies designed to help become the source of great pain, vast damage and prevent or destroy the ability to build real wealth. This article has reviewed the origins of the farm loan programs and future articles will review their further development.

Source : illinois.edu