By Tamra Jackson-Ziems and Kyle Broderick

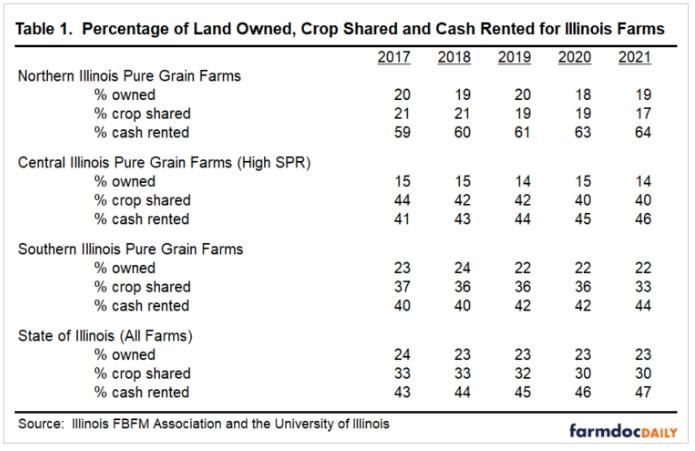

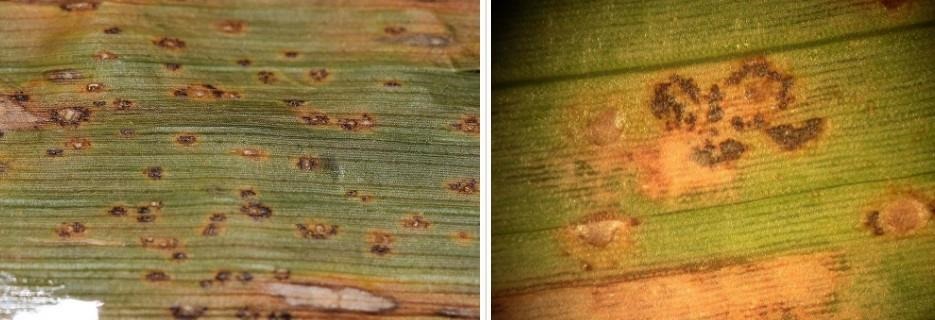

Tar spot, caused by Phyllachora maydis, was confirmed in several eastern Nebraska counties during recent weeks (Figure 1). Tar spot initially developed in western Iowa in September 2019, but was seemingly inactive since then when conditions were dry. However, with the development of rain showers in the region, colleagues from Iowa State University were able to confirm active tar spot in all of the westernmost counties of Iowa along the Missouri River during recent weeks.

Figure 1. Tar spot disease of corn has been confirmed on samples from corn fields in several eastern Nebraska counties.

During a collaborative survey trip through northeast Nebraska, we identified tar spot in corn fields in Dakota, Thurston and Burt counties, indicating that the fungus causing tar spot has moved into Nebraska. Disease could be found in every field where we stopped that week — albeit at very low severity and incidence, making it difficult to find the tiny black “dots” on leaves. However, it was often easier to see them on the few remaining green leaves than on brown, senesced leaves.

Also complicating the search for tar spot was the presence of rust diseases on leaves — especially southern rust, which was common in 2021 (and other years). Since then, samples with tar spot have been submitted from other counties in eastern Nebraska, including Richardson County in the extreme southeast corner of the state, and from as far west as York County. There are likely additional corn fields in other counties where the disease can be found.

History and Impact

Tar spot was first reported in the Midwest United States in 2015. Since then the disease has continued to spread through the Corn Belt. Often, the disease develops late season during cool, damp conditions in the fall and causes little damage. However, early and severe tar spot has reportedly caused yield loss of up to 25-30% in some Midwestern fields. The disease was first identified in Mexico in 1904 and has been a problem in other Latin American countries, where it is caused by a complex of multiple fungi and has impacted grain production, causing yield losses of 11-46%. The disease can also impact quality of other corn products, including silage, stover and husks.

Distribution maps of locations where tar spot has been confirmed in the U.S. by county can be found at the Corn ipmPiPE Tar Spot website. Corn ipmPiPE also supports the Southern Rust distribution website. When viewing these maps, keep in mind that counties that are highlighted indicate that a sample from one or more fields in that county tested positive. Counties that are not highlighted does not indicate an absence of the disease. Likewise, highlighted counties do not imply that every field is affected or indicate severity of the disease in the fields where it was found.

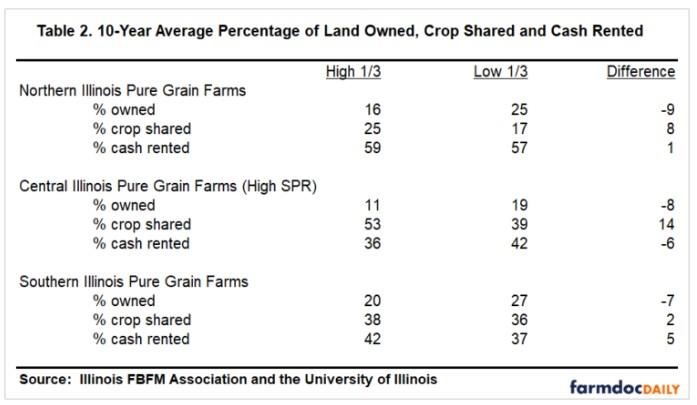

Figure 2a-2b. The classic symptom (sign) of tar spot is the presence of black, raised fungal structures on the leaf or husk surface, called ascomata or stromata.

Figure 2a-2b. The classic symptom (sign) of tar spot is the presence of black, raised fungal structures on the leaf or husk surface, called ascomata or stromata. Figure 2b

Figure 2b Figure 3. Phyllachora maydis causing tar spot can produce two types of spores in the black stromata on the corn leaf surface. Thin, narrow asexual conidia may be produced in large numbers and sexual ascospores produced inside an ascus (pictured) may be visible (200x).

Figure 3. Phyllachora maydis causing tar spot can produce two types of spores in the black stromata on the corn leaf surface. Thin, narrow asexual conidia may be produced in large numbers and sexual ascospores produced inside an ascus (pictured) may be visible (200x).Symptoms

Tar spot produces small, raised black spots across the upper and lower leaf surfaces that cannot be scraped off the leaf surface (Figure 2). These black structures are called stromata or ascomata (a type of fungal fruiting structure) and may be circular or elongated. A tan to brown halo may surround the ascomatum, giving it a “fisheye” lesion. When the ascomatum is viewed under magnification, sausage-shaped asci (spore cases) are visible (Figure 3).

A preliminary identification can be made in the field; however, microscopic confirmation is needed to differentiate tar spot from other pathogens, especially later in the growing season. Both common rust and southern rust produce black teliospores (Figure 4) late in the season that can easily be confused with tar spot. Rust pustules can be rubbed off with a fingernail and often leave an orange to black mark on your finger.

Tar spot may also be confused for any number of saprophytic organisms (Figure 5) that readily grow on dead and dying leaf tissue. These saprophytes usually have a dusty appearance, are likely to be rubbed off and may not produce raised bumps.

Samples with suspected tar spot may be sent to the UNL Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic for confirmation. If samples suspected of tar spot are the first report in a county, they will be processed free of charge.

Figures 4a and 4b. Rust fungi can also produce black spores and structures late season. Southern rust was common in some Nebraska fields in 2021 and the presence of black telia and teliospores (Figure 4a) will make identifying tar spot stromata on leaves more difficult. Remember that black rust telia are usually produced adjacent to or around old rust pustules in rings or horseshoe shapes (Figure 4b, 60x).

Favorable Conditions

Figures 5a and 5b. Beneficial saprophytic fungi are common this year and visible on corn. They can begin degrading plant tissue at the end of the season, producing dark spots that may be confused with those of tar spot. Note that these are not raised above the leaf surface like the stromata of tar spot.

There are still unanswered questions about the biology and life cycle of the fungus causing tar spot. Cooler temperatures (optimally 60-70°F) and seven or more hours of damp conditions seem to be most favorable for disease development and spread. The fungus overwinters in infested crop debris so disease will redevelop in the same areas once the fungus is established there and weather conditions are favorable again for the fungus to reproduce and infect.

Management

Foliar fungicides have been effective at managing tar spot during the growing season but must be applied near disease onset for best results. You can see efficacy ratings for tar spot (and other diseases) for specific products in the Crop Protection Network’s publication Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Corn Diseases. Routine scouting for diseases is important when making fungicide application timing decisions. Disease development and severity depend on hybrid susceptibility, weather/field conditions, disease history, and several other factors that will impact whether a fungicide will be necessary or economical.

Recent studies in the eastern Corn Belt have demonstrated that corn hybrids varied in their reaction to tar spot. Some seed companies have already begun to provide hybrid disease ratings for tar spot and you should avoid planting highly susceptible corn hybrids in eastern Nebraska fields where we expect tar spot is likely to redevelop. You should work with seed company agronomists to select corn hybrids that are expected to perform best under your field conditions.

Crop rotation to other crops may help to reduce disease severity in future years, although it’s unknown how many years will be needed to reduce the amount of overwintering fungal inoculum that will cause disease later. Alternative host species have been identified for this fungus, as well.

Little research has been conducted on the impact of irrigation on tar spot. Limited anecdotal evidence from other states suggests that disease severity can be increased under overhead irrigation versus in non-irrigated fields, because of the wetter conditions in the canopy that support fungal reproduction and movement. Thus, the risk of tar spot is likely greater in irrigated fields and those fields should be more closely monitored for disease development during the season.

Because the fungus overwinters in infested crop debris, tillage may help to decompose affected tissue and reduce disease later but is not practical in all scenarios and won’t eliminate disease pressure. Movement of infested corn plants and tissue will likely move the fungus to new areas, so be mindful of the geographic area where corn is produced when moving stover or other cattle feed products to avoid or limit accidental introduction of this and other pathogens to new areas.

Source : unl.edu