By Jared Goplen

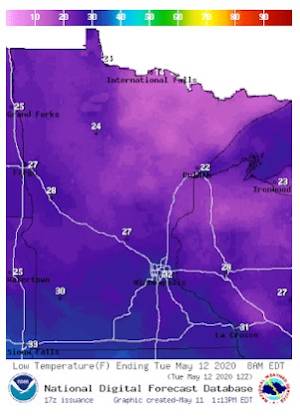

The recent cold weather has caused stress for many emerged crops in Minnesota, including forages. The warm weather earlier this spring allowed many alfalfa stands to produce significant spring growth, with stands in some areas approaching one foot, or more, in height. Some alfalfa fields have experienced frost damage with the recent sub-freezing temperatures, with the greatest potential for frost injury occurring this morning (5/12) (Figure 1).

Alfalfa is relatively tolerant of cold temperatures, especially smaller plants. Most stands should recover just fine with no more than a few frosted leaves (Figure 2).

This article includes several important points on managing frosted alfalfa stands.

Air temperature doesn’t mean alfalfa temperature

Frost injury to alfalfa can be difficult to predict, as microclimates around or within fields of alfalfa can have large influences on the actual temperature of alfalfa plants. Air temperature readings are often reported from several feet above the soil surface. Actual temperatures within the forage canopy can differ from air temperature depending on the density of the forage, wind speed, soil moisture, and soil temperature. Individual plants can also differ in freezing tolerance depending on the variety and stage of development.

Alfalfa is relatively cold tolerant

Alfalfa can generally withstand temperatures down to 24F for several hours without damaging more than the leaves in the mid- to upper-canopy. Temperatures from 25F to 30F may freeze leaves, but will likely not kill the apical meristem (bud) at the top of the plant. The meristem has added protection from the developing leaves surrounding the meristem that provide additional insulation. When temperatures warm up, the surviving meristems should continue normal growth.

Newly-seeded alfalfa has excellent cold tolerance, especially before emergence of the second trifoliate. Cold tolerance diminishes some with older seedlings, but newly seeded stands should survive as long as temperatures do not go below 26F for more than four hours.

Patience is key to managing frosted alfalfa

Waiting several days is the first step in managing frost-damaged alfalfa. Leaf injury will likely be obvious as soon as temperatures warm up, as affected leaves will begin to wilt and change color. If stems have been damaged, they will also wilt. Stems can appear wilted but straighten up again after several days, which is why it is important to be patient in evaluating the full extent of damage. If stems straighten up again, or if stems were not affected, normal growth should resume with little to no yield penalty.

- If only the uppermost leaves show frost symptoms, such as black or brown tissue throughout leaves or on leaf margins, the stand will continue to grow fine with minimal, if any, first cutting yield loss.

- If the entire upper canopy turns black, brown, or necrotic, this means the meristematic tissue (bud) was killed by frost and will not continue growth. Unfrosted axillary stems will continue growing from lower on the stem and from crown buds. This growth will take slightly longer to develop, and may delay first cutting.

- If there is enough biomass to warrant harvest (>15-20 inches tall), the frosted alfalfa could be harvested to capture frosted leaves and stems that will soon fall off.

- If there is not enough biomass to warrant harvest (<15-20 inches tall), allow the axillary and crown buds to continue growth until the stage of normal first-cutting. Yield will likely be somewhat reduced and harvest will likely be delayed.

- If new seedings turn brown, black, or necrotic, the plants will not regrow and will need to be reseeded. If some areas of the field survived while others died, reseed only areas that were injured or killed.

Source : umn.edu