By Daniel Munch

For nearly 100 years, the history of the farm bill largely tracks the history of food production in the United States as the legislation has evolved to meet the needs of farmers and consumers alike. Agriculture’s role in providing food security, and in turn national security, to the United States is more important than ever. And now, work on the next farm bill continues during a period of volatility on every front – political, economic, environmental and beyond.

Farming and ranching are not for the faint of heart. Taking on a substantial amount of risk is part of the business. The year starts with a farmer making extensive investments by purchasing inputs like seed, fertilizer, equipment and its maintenance, fuel, crop protectants and pest control, which can easily total hundreds of thousands of dollars. That’s just to get a crop in the ground. Those investments can be wiped out, suddenly, with a single destructive weather event, pest infestation or disease that causes a crop loss or decline in revenue. After successfully navigating mother nature, farmers who harvest a crop still face massive risk as price-takers in commodity markets with significant price volatility by the time that crop is ready to be sold.

Given historically slim, and often negative, profit margins, farmers are often reliant on lines of credit borrowed from financial institutions at the cost of interest. When all or nearly all of a crop is lost, farmers, who don’t have significant cash reserves to begin with, risk defaulting on their loans and losing their farm. Without some form of risk management protection in place, the liability of farming becomes impossible to maintain. Crop insurance is not merely a safety net but a lifeline for farm businesses, the rural communities they support and the food supply. The 2024 Feeding the Economy study found that the U.S. food and agricultural sectors directly support nearly 24 million jobs (over 15% of U.S. employment) and more than $9.6 trillion of the nation’s economic activity (20% of total U.S. economic output).

This article reviews the comparative cost of crop insurance and makes the case for why crop insurance is a critical tool in the toolbox, that when aligned with other Title I farm bill programs keeps U.S. farmers farming and U.S. consumers fed and fueled. An overview of crop insurance basics is provided here. Livestock and dairy risk management programs have been discussed in Livestock and the Farm Bill and Overview of Dairy Programs in the Farm Bill.

Low Federal Spending

The Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) is authorized by the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 and the Federal Crop Insurance Act of 1980 and operates as a public-private partnership. Through farm bills and appropriations, Congress makes changes to the program, expands coverage and directs research. USDA, through the Risk Management Agency (RMA) and the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), supports a portion of premiums needed for farmers to acquire insurance plans and compensates Approved Insurance Providers for the cost of administering and delivering those plans.

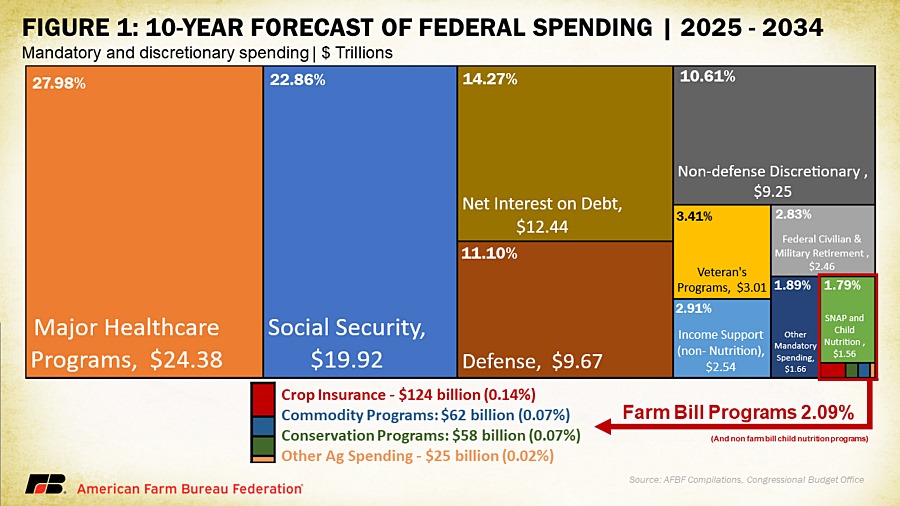

In February 2024, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that crop insurance expenses from 2024 to 2034 would total $124 billion, accounting for approximately one-tenth of 1% of total projected federal spending. To put this in perspective, CBO projects spending on interest to service public debt at $12.44 trillion during this same period, over 100 times larger than the cost of delivering and administering crop insurance. The entire farm bill, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), plus non-farm bill nutrition programs represent only 2.09% of the total federal budget. Just 2% of federal spending directly supports essential farm and nutrition programs crucial for food security, farm economic sustainability, conservation and natural resource preservation efforts.

At its core, crop insurance is the farm bill program that keeps farmers farming year-to-year, maintaining a supply of domestically grown agricultural products to feed and fuel consumers at home and abroad. In the words of my grandfather, “Nothing is free.” So, how much would, or should, a taxpayer pay for this service? A standard Netflix subscription is currently $15.49 a month and a Starbucks coffee ranges from $1.94 to over $4.95 per cup. Based on RMA’s calculations of direct costs of the FCIP, on average, crop insurance has cost each American about $2.18 per month since 2008. Crop insurance costs have remained relatively stable since 2008 and the most recent upticks can be attributed to expanded access to the program proven by the significant increase in number of enrolled policies and increased commodity prices. Optimizing program management and execution to ensure efficient use of taxpayer dollars is vital, but exaggerating the cost of crop insurance to the federal government is detrimental to supporting a secure food supply and having fruitful budget reform.

By statute, crop insurance must be actuarily sound: over time, every dollar paid out in indemnities should match every dollar collected in premiums. Plus, premiums are adjusted as risk conditions change, similar to a driver’s policy if they were in a car accident or accumulated several speeding tickets. These requirements and conditions keep program costs in check.

The Importance of Premium Support

Consider a home insurance example: If you live on the coastline in the hurricane-prone Southeast, you likely pay more for your homeowners’ insurance than someone who lives in the less hurricane-prone Northeast. Likewise, if you’re a newly licensed driver, your car insurance premiums are usually higher than drivers who have a safe driving record over many years. In both cases, premiums, the cost of the policy, are set in terms of risk exposure. The business of growing crops is, comparatively, riskier than driving a car or owning a home. Conditions like freezes and heavy rains rarely destroy homes and cars but can eliminate millions of acres of agricultural production, thus business revenue, in mere hours. Crop insurance offers protection for farm businesses from events completely out of their control. The cost of the premium is shared across the food system because the cost of the policy, due to the high-risk nature of farming, would be too high for farmers to make ends meet from year-to-year. Crop insurance cannot be offered by the private sector alone due to correlated risk. If I get into a car accident, it doesn’t impact my neighbor’s likelihood of getting into a car accident. However, if there is a severe drought in the Midwest, for example, all the farmers in the region will be impacted. This would make crop insurance products financially unattainable for farmers without government support. The premium support keeps the insurance costs from being too high for farmers to make ends meet even during good years. Premium discounts authorized by the farm bill exist to both protect the domestic food system and sustain farmer enrollment.

Premium discounts are set by Congress and are permanent until Congress changes them. Discount rates decrease as coverage levels increase and the corresponding deductible chosen by the farmer decreases. Going back to the car insurance comparison, after a car accident when a car is considered totaled, the insurance policy usually pays equal to the vehicle’s actual worth minus the deductible chosen by the insured. This deductible can be anywhere from zero to a couple of thousand dollars. Even at the highest levels of crop insurance coverage, individual crop insurance plans pay a maximum of 85% of the expected value of the crop. This means 15% of the liability of a farmer’s crop is lost as a deductible, which can equal tens of thousands of dollars even for the most expensive policy. Yet farmers still purchase at that level because it’s so essential to their risk management. Some farmers will purchase additional supplemental and enhanced coverage options that can lift coverage levels higher, but only up to 95% of expected value, not 100% (this differs from some livestock insurance products that do offer protection of up to 100% of the expected ending value).

For most farmers, selected coverage levels are closer to the 70% range, meaning farmers must experience a 30% decline in actual revenue (under expected revenue) before crop insurance comes into play. Figure 2 displays the average per acre revenue decline farmers must absorb before crop insurance is triggered. For example, an average corn farmer must face over $204 in lost revenue per acre before crop insurance would trigger, a bit more than 31% of the total value of the crop. To put things in perspective, in 2023, the cost to grow and harvest an acre of corn in Illinois (excluding any cash rent) was estimated at $812. For a 350-acre farm this means the same farmer would have to face over $70,000 in revenue losses before crop insurance is triggered, an area of land that easily could cost $284,000 to farm.

Factors Leading to Increased Indemnities

There are quite a few reasons indemnities have increased. In recent years, market conditions have driven up the prices of many crops. When the program insures farmers’ crops at these higher market-driven prices, it naturally results in higher payouts in the event of crop losses or a decline in revenue. To illustrate, consider having car insurance for a 2012 model of a non-luxury car and then upgrading to a 2024 model of the same car. The value of the new car far exceeds that of the old one. If both cars were totaled, the insurance plan for the newer model would pay out more due to its higher market value. Similarly, elevated commodity prices between 2011-2012 and 2021-2022 have led to higher insured liabilities and associated indemnity payments compared to periods of lower prices in between.

Moreover, the FCIP has expanded its offerings significantly over the past two decades. From 2000 to 2023 the number of policies sold has increased from 1.94 million to 2.34 million, and insured acreage has correspondingly swelled from 206 million to 539 million acres. More coverage options for more crops incentivizes more enrollment, leading to higher overall insured liabilities and corresponding indemnities. Between 2000 and 2023, liabilities have increased from $34 billion to $181 billion. Of note, this time period also saw an increase in farmer-paid premiums from $1.59 billion to $6.78 billion. Broader participation from more farms in more locations that grow different crops and are of different sizes balances the overall risk pool and contributes significantly to the stability of the crop insurance program.

Importantly, the percentage of liabilities indemnified reveals whether losses are becoming increasingly larger. Between 2000 and 2023, an average of 8% of liabilities were indemnified under crop insurance with no upward trend in losses present. An indemnification rate of 8% was even common between 2000-2011 and 2012-2023, showing that as the program grew, payouts did not become proportionally higher. Indemnified liabilities peaked in 2012 at 15% during a massive drought. Rains in 2019 caused over 20 million acres of prevented planting, pushing indemnified liabilities up to 10%. In 2022 extreme drought pressured plans again with 11% of liabilities indemnified. Comparatively low losses in other years offsets years with major weather disasters. In 2023 indemnified liabilities were only 7%. As crop insurance options continue to become more widely available, participation will increase, which also leads to a higher likelihood of more indemnities triggered when a severe event occurs. Crop insurance works when payments are made when a qualifying loss occurs. If you receive a payment from your auto insurer after an accident that’s usually a positive experience, not a negative one. A crop insurance program that effectively supports producers during times of loss is a working program.

Gaps Still Exist for Specialty Crop Growers

Critics often define crop insurance by what it doesn’t cover. There are gaps that leave producers of certain crops and in certain regions with few-to-no risk management options. Specialty crops, for example, often face higher levels of risk than crops grown at substantially higher volumes. Increased sensitivity to weather, pests and diseases; increased reliance on labor; and more uncertainty in price and the ability to find buyers all increase risks for specialty crop growers. Establishing data-heavy actuarily sound crop insurance policies for products sold in thinner markets, with fewer buyers and sellers, is an uphill battle. A previous article, Specialty Crop Considerations for the Farm Bill, dives deeper into these dynamics.

Significant advances have been made in providing more coverage for fruit, vegetable and nut growers. Coverage options have expanded with over 80 commodity and sub-commodity categories added since 1989. According to RMA summary of business data, in 1989 there were 28,375 specialty crop policies sold. As of 2023, specialty crop policies sold reached over 120,000 – more than quadrupling in the past 34 years. Liabilities from specialty crop polices have increased from $9.2 billion in 2003 to $23.2 billion in 2023, which speaks to the increased number of policies and price value of the specialty crops covered. Specialty crops hold 14% of total U.S. crop insurance liabilities, but, by value, represent 21% of all crops grown in the U.S. The top specialty crops covered in these policies include almonds, grapes, apples, potatoes, orange trees and tomatoes.

Click here to see more...